ST MARY AND ST ANDREW. The most ambitious church in this NW corner of Suffolk, 168 ft long with a tower 120 ft high. The church stands in the middle of the town, though isolated by its oblong churchyard. Its E end overlooks the High Street. It is in this E end that the earliest architecture is to be found: the chancel and the N chapel, dating back to c. 1240-1300. The N chapel comes first, work perhaps of an Ely mason. It is of limestone, not of flint, two bays long with an elegant rib-vault inside in which the transverse arches and the ribs have the same dimensions and profile. At the E end are three stepped lancets, and they are shafted inside with detached Purbeck shafts carrying stiff-leaf capitals. The chancel arch is of the same date, a beautiful piece, nicely shafted, with keeling to the shafts and excellent stiff-leaf and crocket capitals. Also small heads. But the chancel was built slowly. The Piscina still belongs to the previous jobs. It has Purbeck shafts and stiff-leaf capitals. The top of the Piscina is not genuine. The Sedilia are no more than three stepped window seats, separated by simple stone arms. But the windows are definitely of c. 1300. The N and S windows alternate enterprisingly between uncusped intersected tracery and three stepped lancet lights under one arch, but with the lower lights connected with the taller middle one by little token flying buttresses. The E window is a glorious and quite original design, heralding the later one of Prior Crauden’s Chapel at Ely. Seven lights, the first and last continued up and around the arch (as in that chapel) by a border of quatrefoils. The next two on each side are taken together as one and have in the spandrel an irregular cusped triangle. Over the middle stands a big pointed oval along the border of which run little quatrefoils again. The centre is an octofoiled figure.

There is no Dec style at Mildenhall. Perp the W tower first of all. Angle buttresses with attached shafts carrying little pinnacles (a Somerset motif). Big renewed doorway, big renewed six-light W window with a tier of shields at its foot. Inside on the ground floor the tower has a tunnel-like fan-vault. Above this the unusual motif of a choir gallery open to the nave, with a stone balustrade. Perp also are the arcades between nave and aisles. They have very thin piers with finely moulded shafts and capitals only towards the arch openings. Shafts rise from these right up to the roof. Perp moreover the renewed clerestory windows and the big aisle windows. The N side is richer than the S. There is a little flushwork decoration here and there on battlements with panel decoration in two tiers and with pinnacles. This is the crowning motif of the N porch too. The porch is long and two-storeyed. Niches in the buttresses, shields above the entrance. Vault inside with ridge-ribs, tiercerons, and bosses. On the upper floor was the Lady Chapel (as at Fordham in Cambridgeshire a few miles away). The S porch is simpler. Excellent nave roof of low pitch, with alternating hammerbeams and cambered tie-beams. The depressed arched braces of the tie-beams are traceried, and there is tracery between the queenposts on the tie-beams. Against the hammerbeams big figures of angels. Angels also against the wall-plate. The aisle roofs have hammerbeams too. In the spandrels of those in the N aisle carved scenes of St George and the Dragon, the Baptism of Christ, the Sacrifice of Isaac and the Annunciation. Against the wall-posts figures with demi-figures of angels above them serving as canopies. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, of Purbeck marble with shields in quatrefoils. - NORTH DOOR. With tracery. - PLATE. Cup 1625; Almsdish 1632 ; Cup and Paten 1642; two enamelled Pewter Dishes given in 1648; Flagon given in 1720. - MONUMENT. Sir Henry North d. 1620. Alabaster. Two recumbent effigies. The children kneel below, against the tomb-chest. Background with two black columns, two arches, two small obelisks, and an achievement. - In the churchyard the so-called Read Memorial, in fact the remains of a CHARNEL HOUSE with a chapel of St Michael over. The chapel was endowed in 1387.

MILDENHALL. It has come into a fame it could never have dreamed of in all its centuries, for there was a day on which its name was in every newspaper and on all men’s lips. It is odd that here should sleep the winner of the first Derby, for it was here, where this grave sets us thinking of the speed of a horse, that men set out on a ride compared with which the speed of a Derby winner is that of a tortoise. At Mildenhall began the greatest achievement of speed ever known then, the air race to Australia. This pleasant border town by the River Lark, with miles of firs and fine pine avenues, was the starting-point of the two men who flew across the earth in three days in 1934; they were Charles Scott and Campbell Black and they reached Melbourne from Mildenhall in just under 71 hours. It was the fastest journey across the earth ever known.

The place which thus came into fame in the 20th century goes back as far as the Stone Age, for strewn about its heaths we find worked flints which were the precious tools and weapons of men then. Warren Hill has the quiet graves of Saxons. The church is 13th century, and keeping company with it is an old mill by the river, a fine medieval wooden cross, with a handsome lead roof resting on rough-hewn pillars, homes going back to Tudor days, and 18th century almshouses founded by a Speaker of the House of Commons who helped to secure the Protestant Succession to the throne and gave the world its first fine Shakespeare.

The magnificent church, 700 years old, 170 feet long, and with a tower 120 feet high, is one of the county’s proud possessions, which Cambridgeshire sees from afar as the sun gilds its gay weathercock. The exterior is rich with carving. Above an aisle is a fine panelled parapet; and the buttresses are lavishly decked with canopied niches, of which there are 13 on the buttresses at the east corners alone.

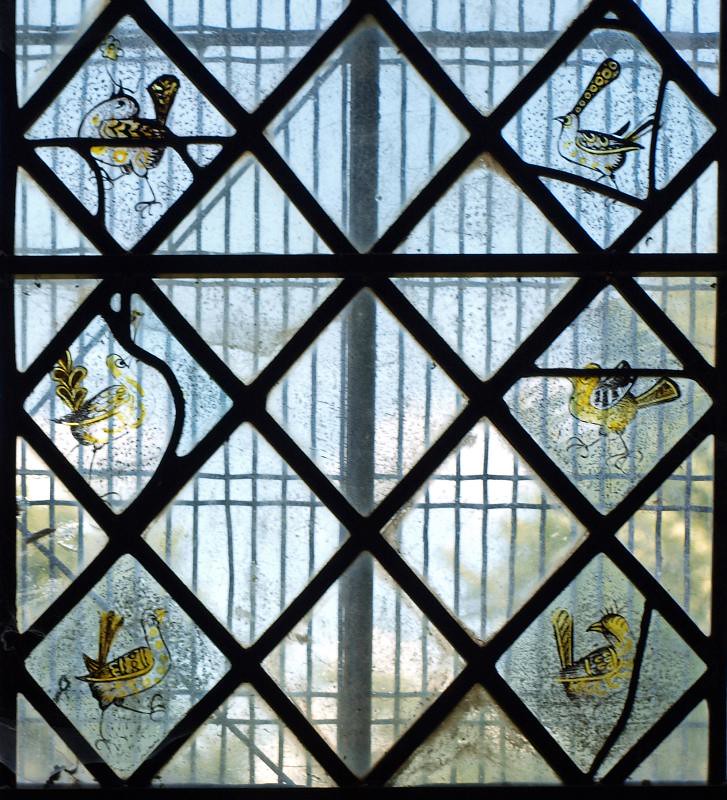

Two graceful porches the church has, the north one 30 feet long (the biggest in Suffolk), with a beautiful vaulted roof with angels and roses on its bosses. Above it is the old schoolroom, with quaint figures carved in the spandrels of its doorway. Under the tower with its fine bold arch is a splendid fan-tracery roof; and a vaulted stone roof covers the 13th century chapel. The nave has lofty 15th century arches, and at either side of the 700-year-old chancel arch are three columns with fine foliage capitals. The piscina and sedilia are about as old as Magna Carta. A striking feature of the 13th century sanctuary window is the adaptation of charming new glass to old architecture. Above the arch of the window are 12 small medallions; between these and the seven slender lights below is an oval like a ring set with jewels.

It is the woodwork for which the church is famous. The pulpit, in memory of a parishioner who was 53 years a churchwarden, is one of the few examples of modern workmanship; the rest is a splendid bequest of the past, instinct with medieval character, work performed in the spirit of some of the old miracle plays, in which religious ecstasy alternates with riotous humour. On the hammerbeams of the 15th century nave roof, one of the finest in the county, are two big angels and some 60 lesser ones, some with books, some with musical instruments, all with outspread wings; even the tiebeams are carved and embattled. The south aisle roof, on which are the swan and antelope of Henry the Fifth, is crowded with ornament; on its fine hammerbeams, in the spandrels and along the cornice, are saints and priests, pelicans and eagles, a dog, a monkey, a squirrel, doves, and a mass of about 160 figures. Finest of all is the north aisle roof. Seven fantastic stone heads carry the splendid, harnmerbeams, between which are saints finely carved with a touch of individual fancy, each secure in the shelter of an angel’s wings. In the spandrels is a gallery of the sublime, the humorous, and the sardonic. Mingled with Bible scenes are a woman in a horned headdress supposed to typify Pride, a comic pig with an astonishing collar, one monkey playing an organ while another blows the bellows, and a demon grasping a dog by its tail.

Many monuments tell the story of six centuries of Mildenhall men. The oldest is that to Sir Richard de Wychforde, the 13th century vicar who built the chancel. His brass portrait is gone, but his tomb is safe below the beautiful window which took shape at his bidding. Under the tower lies Sir Henry de Barton, Lord Mayor in the year after Agincourt, and remembered as having started the lighting of dark benighted London, for it was he who first ordered the people to hang out lights from their houses. Here also rests the builder of the manor house, Sir Henry North; he lies on an alabaster tomb with his wife, both smiling happily. In the chancel lies his grandson Thomas Hanmer, a baronet and an MP at 24 and Speaker at 37. Resisting attempts to win him over to the Pretender, he defended the Protestant Succession, and, when that was made safe by the proclamation of George the First, retired to spend his last 20 years here. Working in his fine library he produced the first nobly printed Shakespeare, making several corrections of errors in the text; his own copy, the Hanmer Fourth Folio, was discovered in 1917 and is in the Bodleian Library.

The church has many monuments to the Bunbury family, which gave it a vicar for over 50 years. Sir Thomas was the winner of the first Derby (with Diomed), and sat in Parliament for 43 years. It was his nephew Sir Henry, soldier, diplomatist, and reformer, whose vote gave the Reform Bill its majority of one, who was chosen for his tact and good nature to communicate to Napoleon the crushing news of the Government’s decision to exile him to St Helena. Sir Henry’s father was the artist Henry William Bunbury, friend of Goldsmith and Reynolds, whose famous “Master Bunbury” is a portrait of the General’s younger brother. Another Bunbury here, a little boy of five who died in 1749, is described as a lovely child who showed great promise. There is one brass portrait, showing the builder of Wamil Hall, a mile away, Sir Henry Warner, wearing armour of the time of James the First, and apparently in the act of putting on his gloves.

Two miles away is the big agricultural village of West Row, with a church built from the materials of the old National School; it has a window in memory of Lawrence Clutterbuck, a curate’s son who gave his life to save a student from drowning.

The place which thus came into fame in the 20th century goes back as far as the Stone Age, for strewn about its heaths we find worked flints which were the precious tools and weapons of men then. Warren Hill has the quiet graves of Saxons. The church is 13th century, and keeping company with it is an old mill by the river, a fine medieval wooden cross, with a handsome lead roof resting on rough-hewn pillars, homes going back to Tudor days, and 18th century almshouses founded by a Speaker of the House of Commons who helped to secure the Protestant Succession to the throne and gave the world its first fine Shakespeare.

The magnificent church, 700 years old, 170 feet long, and with a tower 120 feet high, is one of the county’s proud possessions, which Cambridgeshire sees from afar as the sun gilds its gay weathercock. The exterior is rich with carving. Above an aisle is a fine panelled parapet; and the buttresses are lavishly decked with canopied niches, of which there are 13 on the buttresses at the east corners alone.

Two graceful porches the church has, the north one 30 feet long (the biggest in Suffolk), with a beautiful vaulted roof with angels and roses on its bosses. Above it is the old schoolroom, with quaint figures carved in the spandrels of its doorway. Under the tower with its fine bold arch is a splendid fan-tracery roof; and a vaulted stone roof covers the 13th century chapel. The nave has lofty 15th century arches, and at either side of the 700-year-old chancel arch are three columns with fine foliage capitals. The piscina and sedilia are about as old as Magna Carta. A striking feature of the 13th century sanctuary window is the adaptation of charming new glass to old architecture. Above the arch of the window are 12 small medallions; between these and the seven slender lights below is an oval like a ring set with jewels.

It is the woodwork for which the church is famous. The pulpit, in memory of a parishioner who was 53 years a churchwarden, is one of the few examples of modern workmanship; the rest is a splendid bequest of the past, instinct with medieval character, work performed in the spirit of some of the old miracle plays, in which religious ecstasy alternates with riotous humour. On the hammerbeams of the 15th century nave roof, one of the finest in the county, are two big angels and some 60 lesser ones, some with books, some with musical instruments, all with outspread wings; even the tiebeams are carved and embattled. The south aisle roof, on which are the swan and antelope of Henry the Fifth, is crowded with ornament; on its fine hammerbeams, in the spandrels and along the cornice, are saints and priests, pelicans and eagles, a dog, a monkey, a squirrel, doves, and a mass of about 160 figures. Finest of all is the north aisle roof. Seven fantastic stone heads carry the splendid, harnmerbeams, between which are saints finely carved with a touch of individual fancy, each secure in the shelter of an angel’s wings. In the spandrels is a gallery of the sublime, the humorous, and the sardonic. Mingled with Bible scenes are a woman in a horned headdress supposed to typify Pride, a comic pig with an astonishing collar, one monkey playing an organ while another blows the bellows, and a demon grasping a dog by its tail.

Many monuments tell the story of six centuries of Mildenhall men. The oldest is that to Sir Richard de Wychforde, the 13th century vicar who built the chancel. His brass portrait is gone, but his tomb is safe below the beautiful window which took shape at his bidding. Under the tower lies Sir Henry de Barton, Lord Mayor in the year after Agincourt, and remembered as having started the lighting of dark benighted London, for it was he who first ordered the people to hang out lights from their houses. Here also rests the builder of the manor house, Sir Henry North; he lies on an alabaster tomb with his wife, both smiling happily. In the chancel lies his grandson Thomas Hanmer, a baronet and an MP at 24 and Speaker at 37. Resisting attempts to win him over to the Pretender, he defended the Protestant Succession, and, when that was made safe by the proclamation of George the First, retired to spend his last 20 years here. Working in his fine library he produced the first nobly printed Shakespeare, making several corrections of errors in the text; his own copy, the Hanmer Fourth Folio, was discovered in 1917 and is in the Bodleian Library.

The church has many monuments to the Bunbury family, which gave it a vicar for over 50 years. Sir Thomas was the winner of the first Derby (with Diomed), and sat in Parliament for 43 years. It was his nephew Sir Henry, soldier, diplomatist, and reformer, whose vote gave the Reform Bill its majority of one, who was chosen for his tact and good nature to communicate to Napoleon the crushing news of the Government’s decision to exile him to St Helena. Sir Henry’s father was the artist Henry William Bunbury, friend of Goldsmith and Reynolds, whose famous “Master Bunbury” is a portrait of the General’s younger brother. Another Bunbury here, a little boy of five who died in 1749, is described as a lovely child who showed great promise. There is one brass portrait, showing the builder of Wamil Hall, a mile away, Sir Henry Warner, wearing armour of the time of James the First, and apparently in the act of putting on his gloves.

Two miles away is the big agricultural village of West Row, with a church built from the materials of the old National School; it has a window in memory of Lawrence Clutterbuck, a curate’s son who gave his life to save a student from drowning.