I decided to take advantage of the annual Essex Ride & Stride day to revisit, having checked that they were taking part in the day, four churches that I've always found LNK - Takeley, Great & Little Hallingbury and Farnham.

Of the four the first three were locked and Farnham appears to be now

regularly open (or so the sign in the porch seems to imply but I'm

slightly sceptical since I've never found it open on numerous visits).

Now I'm not one to rant but given that, apart from raising huge amounts of money for church conservation, one of the purposes of this event is that it "opens

the doors to some of Britain’s most rare and unusual churches, chapels

and meeting houses" (I readily admit that none of the four could be

described as rare or unusual) but I hope, given the half hearted participation of the first three, that if they ever approach FoECT for a grant they're told to bugger off.

Index

▼

Saturday, 13 September 2014

Saturday, 2 August 2014

London, Covent Garden - St Paul

St Paul appears to be usually open but was closed for a month while they ran a kids club production of Alice in Wonderland so I failed to see inside, although I suspect that it is very austere and dour (which a glance through Flickr proves wrong as shown by Rex Harris and others).

The exterior is hard to judge without perambulation but the east end is neoclassical and should be rather grand, if plain, but for the fact that it now plays host to the Covent Garden mummers which somewhat detracts its impact.

Supposedly designed by Inigo Jones in 1633 it was burnt out in 1795 and was effectively rebuilt by Thomas Hardwick (who had restored it in 1789); so I suppose it's therefore a C17th core but a C18th build. Apparently it has a Grinling Gibbons pulpit which would have been interesting to see.

The exterior is hard to judge without perambulation but the east end is neoclassical and should be rather grand, if plain, but for the fact that it now plays host to the Covent Garden mummers which somewhat detracts its impact.

Supposedly designed by Inigo Jones in 1633 it was burnt out in 1795 and was effectively rebuilt by Thomas Hardwick (who had restored it in 1789); so I suppose it's therefore a C17th core but a C18th build. Apparently it has a Grinling Gibbons pulpit which would have been interesting to see.

The Earl of Bedford himself noted in his commonplace book: “London the Ring Couengarden the iewell of that ring.” He was clearly proud of his estate, but for all that, he looked carefully at the money he was laying out on the new investment. He was responsible for the church and for perhaps three of the houses on the eastern side, as examples to those who wished to take up building leases. When it came to the church, he sent for Inigo Jones and

told him he wanted a chapel for the parishioners of Covent Garden, but added he would not go to any considerable expense; “In short”, said he, “I would not have it much better than a barn.” “Well! then,” said Jones, “You shall have the handsomest barn in England.”

This story has often been told but it bears repeating for St Paul’s, Covent Garden, does indeed resemble a barn, being very plain, with great over-hanging eaves and a portico before the eastern front, which faced the Piazza, with heavy fluted columns and uncompromisingly plain Tuscan capitals. Inside, the church was equally unadorned, which would have agreed with the earl’s severe religious tenets, but Inigo Jones made one miscalculation. If the entrance portico were to face the Piazza, then it would be necessary to place the altar at the west end. Such a deviation was impermissible; the altar was installed in the accustomed position, the congregation entered by the west door, through the churchyard, and the portico stood in front of a blind wall. It was under this portico that Shaw placed Eliza Doolittle in the first act of Pygmalion. St Paul’s, the first Anglican church to be built in London since Tudor times, cost £4,886. 5s. 8d.

told him he wanted a chapel for the parishioners of Covent Garden, but added he would not go to any considerable expense; “In short”, said he, “I would not have it much better than a barn.” “Well! then,” said Jones, “You shall have the handsomest barn in England.”

This story has often been told but it bears repeating for St Paul’s, Covent Garden, does indeed resemble a barn, being very plain, with great over-hanging eaves and a portico before the eastern front, which faced the Piazza, with heavy fluted columns and uncompromisingly plain Tuscan capitals. Inside, the church was equally unadorned, which would have agreed with the earl’s severe religious tenets, but Inigo Jones made one miscalculation. If the entrance portico were to face the Piazza, then it would be necessary to place the altar at the west end. Such a deviation was impermissible; the altar was installed in the accustomed position, the congregation entered by the west door, through the churchyard, and the portico stood in front of a blind wall. It was under this portico that Shaw placed Eliza Doolittle in the first act of Pygmalion. St Paul’s, the first Anglican church to be built in London since Tudor times, cost £4,886. 5s. 8d.

London, Westminster - St Martin in the Fields

An almost perfect early C18th building - all box pews, galleries and neoclassical design - what's not to love? The surviving monuments from the earlier church, and later, are relocated to the crypt alongside a gallery and cafe. If you could just relocate the tourists St Martin would be my ideal urban church.

St Martin’s stands on the north-east comer of the square, traffic swirling past its steps along St Martin’s Place and Duncan Street. There has been a church here since the 12th century when it very truly stood “in the fields”. It is said that the parish was enlarged by Henry VIII’s orders so that funerals might not pass through his palace of Whitehall on their way to burial at St Margaret’s, Westminster, and a new church was built in 1544. By the 18th century, a new structure was needed again and this was built by James Gibbs in 1722-6. He gave it a magnificent temple front with six huge Corinthian columns set on steps; above them is a pediment and from behind that soars the noble spire. The church itself, of Portland stone, is rectangular with galleries. The walls are panelled with unusual box pews and the roof is a tunnel vault. The original organ was given by George I as a compensation for his inability to perform his duties as churchwarden; it is now at St Mary’s, Wootton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, and a new larger instrument has been installed. There is a pretty oval font of 1689, and a hexagonal pulpit with thin twisted balusters. This pulpit was originally a three-decker one, for parson, clerk and reader, and as such it can be seen in Hogarth’s print of the Industrious Apprentice at Church. Charles II was christened. and Nell Gwynn was buried here. St Martin is the patron saint of beggars, of the destitute and of drunkards, so that the noble work of helping the unfortunate, to which the clergy of this church have dedicated themselves, is particularly apt. It was a churchwarden of St Martin’s who tried to help Francis Thompson and it was surely of this church that the poet thought when he wrote of “Jacob’s ladder/ Pitched between Heaven and Charing Cross”. The Reverend Dick Sheppard, who served at the Front in the First World War, returned to St Martin’s determined to create a place where all who were in need could come and find the same unquestioning help and comradeship that he had known in the trenches. He had a vision - “I saw a great church standing in the greatest square in the greatest city in the world” - and he made the crypt of St Martin’s into a club to which all might come and find welcome. His ideals and work have been carried on by those who have followed him.

London, Westminster - St Margaret

The youngest had a hot date with one of his godmothers to see War Horse so I had a couple of hours to fill in London and, unusually, did some research. I already knew I wanted to visit St Martin in the Fields [qv] but baulked at Westminster Abbey's ludicrous £18 entry fee and ban on photography - if I visited with all my children it would cost me £83 just to gain entry. Fuck that...£18 when I can't take photos; what exactly are the poor saps who visit paying for*?

So I researched St Margaret instead and found that photography was allowed and decided here was an opportunity that shouldn't be missed, only to find that photography is banned for these reasons (taken straight from the Abbey website but applies to St Margaret as well):

On the other hand if I could have recorded the interior I probably wouldn't have had time to do it properly since the interior is stuffed with monuments and good windows. So I had quick recce and headed off to St Martin.

* For the record I am quite happy to pay an entry fee and for a photography permit - what I'm not happy about is the extortionate entry fee coupled with the no photography policy.

Flickr.

So I researched St Margaret instead and found that photography was allowed and decided here was an opportunity that shouldn't be missed, only to find that photography is banned for these reasons (taken straight from the Abbey website but applies to St Margaret as well):

- It can disturb other visitors’ experience of the Abbey

- Flash photography is bad for conservation

- It holds up the movement of visitors when there are lots of people in the Abbey

- We have to be careful about and protect what the image of the Abbey is used for - with digital photography and photoshop it is easy for someone to use the image in a way that we aren't happy with or to advertise or promote something

- We can't be sure what is for personal use and what is for professional

This is blatantly bullshit or else Ely, Peterborough, Salisbury, Bury St Edmund, Canterbury, St Albans and Chelmsford would follow the same policy - which they don't.

On the other hand if I could have recorded the interior I probably wouldn't have had time to do it properly since the interior is stuffed with monuments and good windows. So I had quick recce and headed off to St Martin.

To the south-west of the square, on the very lawns of Westminster Abbey sits, composed, demure and quietly self-confident, St Margaret’s church. Though claims have been made for its being an 11th-century foundation, its consecration most probably dates from the early 12th century. The present building was begun at the very end of the 15th century, to plans by Robert Stowell, master mason of the Abbey. The south aisle - the oldest part - was paid for by Dame Mary Billing, the widow of a Chief Justice; she died in 1499. The chancel was built in the early 16th century by John Islip, the last great Abbot of Westminster; his architects were Thomas and Henry Redman. They also built the tower, though the upper parts were rebuilt between 1735 and 1737 by John James. A porch was added by J. Loughborough Pearson in the late 19th century.

The church is chiefly famous for three things - for its association with the House of Commons, for its 16th-century east window, and for the number and variety of its monuments. It was first used by the House of Commons when a service of Holy Communion was held there on Palm Sunday, April 17, 1614. It had been planned to hold it in the Abbey but the more Puritanical Members of Parliament had a “feare of copes and wafer-cakes, and other such important reasons” and so it was held in St Margaret’s instead, and the association has continued ever since. The east window was made to celebrate the marriage of Prince Arthur, Henry VIII’s elder brother, with Katharine of Aragon, but this splendid example of Flemish glass arrived in England after the bridegroom’s death. It was sent to Waltham Abbey, and after that house was dissolved the window passed into private hands and was at last bought for St Margaret’s in 1758 by the House of Commons for 400 guineas. The three central lights show the Crucifixion with the two Thieves on either side of Christ, and in the upper halves of the two outer lights are St George and St Katharine. Beneath the saints kneel the young bride and bridegroom, whose marriage lasted barely five months. Beneath the window is the altar with a reredos which is a relief copy of Titian’s painting of Christ’s appearance at Emmaus; it was made by Siffrin Alken about 1757.

The chancel and nave have no structural division and are of nine bays. Around the walls are scores of small, intimate memorials. Chaucer, who was a parishioner, has no memorial here - he lies in the Abbey - but Caxton was buried here and has a tablet raised by later admirers. His shop was at the sign of the Red Pale and stood within the Abbey Almonry itself. Several of Elizabeth I’s most faithful servants lie here, chief among them perhaps being Blanche Parry, Keeper of the Queen’s Jewels, who died in February 1589 (i.e. 1590) aged 82, having looked after the queen since her birth. Lady Dorothy Stafford, who had served the queen for 40 years, died in 1605, and she is shown kneeling with three sons and three daughters beneath her, whilst Lady Mary Dudley, sister to Lord Howard of Effingham who commanded the English fleet against the Armada, has a fine full-length effigy. A bust in a roundel shows us Cornelius Van Dun, a Dutchman who served Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I as a Yeoman of the Guard and, dying in 1577 at the age of 94, did buyld for poor widowes 2 houses at his own cost. Among all these who had loved the queen is one great man, Sir Walter Raleigh. He fell out of favour with her successor, James I, and after a long imprisonment, was in 1618 executed in Old Palace Yard, in order to please the King of Spain. Raleigh’s courage on the night before his death was remarkable. During the dark hours, he wrote a poem:

Even such is time which takes in trust

Our yowth, our Ioyes and all we have,

And pays us butt with age and dust:

Who in the darke and silent grave

What we have wandered all our wayes

Shutts up the storye of our dayes.

And from which earth and grave and dust

The Lord shall raise me up I trust.

His headless body was buried under the High Altar at St Margaret’s, but his widow kept his head and it is not known whether it was ever re-united with his trunk. The west window in the church, made in the 19th century, has portraits of Raleigh and his half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, as well as Elizabeth I and Henry, Prince of Wales, James I’s eldest son, who admired Sir Walter and wanted to see him freed from prison. Had the prince lived, Raleigh’s fate might have been different.

Those who commanded during the Commonwealth lie here. After their bodies were exhumed with contumely from Westminster Abbey, Admiral Robert Blake, John Pym, Cromwell’s mother and daughter, and 19 others were buried in St Margaret’s churchyard. A later generation has raised a wall-plaque to Blake’s memory. It was in this church that the blind poet, John Milton, was married for the second time. His first marriage had been bitterly miserable but with Katherine Woodcock he was happy for a brief fifteen months. She died in childbed and their baby daughter only survived for six weeks; mother and child were buried together in the churchyard here. They had lived in a “pretty garden-house” in Petty France; Milton lived on alone and wrote:

Methought I saw my late espouséd saint

Come vested all in white, pure as her mind.

Her face was veiled, yet to my fancied sight

Love, sweetness, goodness in her person shined

So clear as in no face with more delight.

But O as to embrace me she inclined

I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night.

A window in Milton’s memory was installed during the last century; it shows the blind poet dictating. Another poet, Alexander Pope, wrote an epitaph for another parishioner, Elizabeth Corbett; it reads:

Here was a Woman good without pretence

Blest with plain Reason and with sober Sense;

No conquests she, but o’er her Selfe, desired;

No Arts essayed; but not to be admired;

Passion & Pride were to her Soul unknown;

Convinced that Virtue only is our own.

So unaffected, so composed a Mind,

So firm, yet soft; so strong, yet so refined,

Heaven as its purest Gold, by Tortures try’d;

The Saint sustained it, but the Woman dy’d.

A more recent memorial, written by Gladstone, is to Charles Frederick Cavendish, who was murdered in Phoenix Park in Dublin May 6, 1882, the very day of his arrival there. In addition to all that we have mentioned, the visitor to the church should notice the modern stained glass, which is designed by John Piper, who created the wonderful windows for Coventry Cathedral. The glass here is softer, less vibrant, chiefly in shades of grey and green and very beautiful; it was installed in 1967.

The church is chiefly famous for three things - for its association with the House of Commons, for its 16th-century east window, and for the number and variety of its monuments. It was first used by the House of Commons when a service of Holy Communion was held there on Palm Sunday, April 17, 1614. It had been planned to hold it in the Abbey but the more Puritanical Members of Parliament had a “feare of copes and wafer-cakes, and other such important reasons” and so it was held in St Margaret’s instead, and the association has continued ever since. The east window was made to celebrate the marriage of Prince Arthur, Henry VIII’s elder brother, with Katharine of Aragon, but this splendid example of Flemish glass arrived in England after the bridegroom’s death. It was sent to Waltham Abbey, and after that house was dissolved the window passed into private hands and was at last bought for St Margaret’s in 1758 by the House of Commons for 400 guineas. The three central lights show the Crucifixion with the two Thieves on either side of Christ, and in the upper halves of the two outer lights are St George and St Katharine. Beneath the saints kneel the young bride and bridegroom, whose marriage lasted barely five months. Beneath the window is the altar with a reredos which is a relief copy of Titian’s painting of Christ’s appearance at Emmaus; it was made by Siffrin Alken about 1757.

The chancel and nave have no structural division and are of nine bays. Around the walls are scores of small, intimate memorials. Chaucer, who was a parishioner, has no memorial here - he lies in the Abbey - but Caxton was buried here and has a tablet raised by later admirers. His shop was at the sign of the Red Pale and stood within the Abbey Almonry itself. Several of Elizabeth I’s most faithful servants lie here, chief among them perhaps being Blanche Parry, Keeper of the Queen’s Jewels, who died in February 1589 (i.e. 1590) aged 82, having looked after the queen since her birth. Lady Dorothy Stafford, who had served the queen for 40 years, died in 1605, and she is shown kneeling with three sons and three daughters beneath her, whilst Lady Mary Dudley, sister to Lord Howard of Effingham who commanded the English fleet against the Armada, has a fine full-length effigy. A bust in a roundel shows us Cornelius Van Dun, a Dutchman who served Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I as a Yeoman of the Guard and, dying in 1577 at the age of 94, did buyld for poor widowes 2 houses at his own cost. Among all these who had loved the queen is one great man, Sir Walter Raleigh. He fell out of favour with her successor, James I, and after a long imprisonment, was in 1618 executed in Old Palace Yard, in order to please the King of Spain. Raleigh’s courage on the night before his death was remarkable. During the dark hours, he wrote a poem:

Even such is time which takes in trust

Our yowth, our Ioyes and all we have,

And pays us butt with age and dust:

Who in the darke and silent grave

What we have wandered all our wayes

Shutts up the storye of our dayes.

And from which earth and grave and dust

The Lord shall raise me up I trust.

His headless body was buried under the High Altar at St Margaret’s, but his widow kept his head and it is not known whether it was ever re-united with his trunk. The west window in the church, made in the 19th century, has portraits of Raleigh and his half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, as well as Elizabeth I and Henry, Prince of Wales, James I’s eldest son, who admired Sir Walter and wanted to see him freed from prison. Had the prince lived, Raleigh’s fate might have been different.

Those who commanded during the Commonwealth lie here. After their bodies were exhumed with contumely from Westminster Abbey, Admiral Robert Blake, John Pym, Cromwell’s mother and daughter, and 19 others were buried in St Margaret’s churchyard. A later generation has raised a wall-plaque to Blake’s memory. It was in this church that the blind poet, John Milton, was married for the second time. His first marriage had been bitterly miserable but with Katherine Woodcock he was happy for a brief fifteen months. She died in childbed and their baby daughter only survived for six weeks; mother and child were buried together in the churchyard here. They had lived in a “pretty garden-house” in Petty France; Milton lived on alone and wrote:

Methought I saw my late espouséd saint

Come vested all in white, pure as her mind.

Her face was veiled, yet to my fancied sight

Love, sweetness, goodness in her person shined

So clear as in no face with more delight.

But O as to embrace me she inclined

I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night.

A window in Milton’s memory was installed during the last century; it shows the blind poet dictating. Another poet, Alexander Pope, wrote an epitaph for another parishioner, Elizabeth Corbett; it reads:

Here was a Woman good without pretence

Blest with plain Reason and with sober Sense;

No conquests she, but o’er her Selfe, desired;

No Arts essayed; but not to be admired;

Passion & Pride were to her Soul unknown;

Convinced that Virtue only is our own.

So unaffected, so composed a Mind,

So firm, yet soft; so strong, yet so refined,

Heaven as its purest Gold, by Tortures try’d;

The Saint sustained it, but the Woman dy’d.

A more recent memorial, written by Gladstone, is to Charles Frederick Cavendish, who was murdered in Phoenix Park in Dublin May 6, 1882, the very day of his arrival there. In addition to all that we have mentioned, the visitor to the church should notice the modern stained glass, which is designed by John Piper, who created the wonderful windows for Coventry Cathedral. The glass here is softer, less vibrant, chiefly in shades of grey and green and very beautiful; it was installed in 1967.

* For the record I am quite happy to pay an entry fee and for a photography permit - what I'm not happy about is the extortionate entry fee coupled with the no photography policy.

Flickr.

Sunday, 6 July 2014

Mildenhall, Suffolk

Superlatives are inadequate when it comes to St Mary, open, for both inside and out. This humungous building has a bit of everything but it's outstanding features are the fan vaulted ceilings in the stunning north porch and the tower minstrel gallery and, above and beyond all, the roofs of the aisles and the nave. The north aisle is particularly fine but the quality of the carving throughout is breathtaking. Without doubt straight in to my personal top ten visited churches.

ST MARY AND ST ANDREW. The most ambitious church in this NW corner of Suffolk, 168 ft long with a tower 120 ft high. The church stands in the middle of the town, though isolated by its oblong churchyard. Its E end overlooks the High Street. It is in this E end that the earliest architecture is to be found: the chancel and the N chapel, dating back to c. 1240-1300. The N chapel comes first, work perhaps of an Ely mason. It is of limestone, not of flint, two bays long with an elegant rib-vault inside in which the transverse arches and the ribs have the same dimensions and profile. At the E end are three stepped lancets, and they are shafted inside with detached Purbeck shafts carrying stiff-leaf capitals. The chancel arch is of the same date, a beautiful piece, nicely shafted, with keeling to the shafts and excellent stiff-leaf and crocket capitals. Also small heads. But the chancel was built slowly. The Piscina still belongs to the previous jobs. It has Purbeck shafts and stiff-leaf capitals. The top of the Piscina is not genuine. The Sedilia are no more than three stepped window seats, separated by simple stone arms. But the windows are definitely of c. 1300. The N and S windows alternate enterprisingly between uncusped intersected tracery and three stepped lancet lights under one arch, but with the lower lights connected with the taller middle one by little token flying buttresses. The E window is a glorious and quite original design, heralding the later one of Prior Crauden’s Chapel at Ely. Seven lights, the first and last continued up and around the arch (as in that chapel) by a border of quatrefoils. The next two on each side are taken together as one and have in the spandrel an irregular cusped triangle. Over the middle stands a big pointed oval along the border of which run little quatrefoils again. The centre is an octofoiled figure.

There is no Dec style at Mildenhall. Perp the W tower first of all. Angle buttresses with attached shafts carrying little pinnacles (a Somerset motif). Big renewed doorway, big renewed six-light W window with a tier of shields at its foot. Inside on the ground floor the tower has a tunnel-like fan-vault. Above this the unusual motif of a choir gallery open to the nave, with a stone balustrade. Perp also are the arcades between nave and aisles. They have very thin piers with finely moulded shafts and capitals only towards the arch openings. Shafts rise from these right up to the roof. Perp moreover the renewed clerestory windows and the big aisle windows. The N side is richer than the S. There is a little flushwork decoration here and there on battlements with panel decoration in two tiers and with pinnacles. This is the crowning motif of the N porch too. The porch is long and two-storeyed. Niches in the buttresses, shields above the entrance. Vault inside with ridge-ribs, tiercerons, and bosses. On the upper floor was the Lady Chapel (as at Fordham in Cambridgeshire a few miles away). The S porch is simpler. Excellent nave roof of low pitch, with alternating hammerbeams and cambered tie-beams. The depressed arched braces of the tie-beams are traceried, and there is tracery between the queenposts on the tie-beams. Against the hammerbeams big figures of angels. Angels also against the wall-plate. The aisle roofs have hammerbeams too. In the spandrels of those in the N aisle carved scenes of St George and the Dragon, the Baptism of Christ, the Sacrifice of Isaac and the Annunciation. Against the wall-posts figures with demi-figures of angels above them serving as canopies. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, of Purbeck marble with shields in quatrefoils. - NORTH DOOR. With tracery. - PLATE. Cup 1625; Almsdish 1632 ; Cup and Paten 1642; two enamelled Pewter Dishes given in 1648; Flagon given in 1720. - MONUMENT. Sir Henry North d. 1620. Alabaster. Two recumbent effigies. The children kneel below, against the tomb-chest. Background with two black columns, two arches, two small obelisks, and an achievement. - In the churchyard the so-called Read Memorial, in fact the remains of a CHARNEL HOUSE with a chapel of St Michael over. The chapel was endowed in 1387.

ST MARY AND ST ANDREW. The most ambitious church in this NW corner of Suffolk, 168 ft long with a tower 120 ft high. The church stands in the middle of the town, though isolated by its oblong churchyard. Its E end overlooks the High Street. It is in this E end that the earliest architecture is to be found: the chancel and the N chapel, dating back to c. 1240-1300. The N chapel comes first, work perhaps of an Ely mason. It is of limestone, not of flint, two bays long with an elegant rib-vault inside in which the transverse arches and the ribs have the same dimensions and profile. At the E end are three stepped lancets, and they are shafted inside with detached Purbeck shafts carrying stiff-leaf capitals. The chancel arch is of the same date, a beautiful piece, nicely shafted, with keeling to the shafts and excellent stiff-leaf and crocket capitals. Also small heads. But the chancel was built slowly. The Piscina still belongs to the previous jobs. It has Purbeck shafts and stiff-leaf capitals. The top of the Piscina is not genuine. The Sedilia are no more than three stepped window seats, separated by simple stone arms. But the windows are definitely of c. 1300. The N and S windows alternate enterprisingly between uncusped intersected tracery and three stepped lancet lights under one arch, but with the lower lights connected with the taller middle one by little token flying buttresses. The E window is a glorious and quite original design, heralding the later one of Prior Crauden’s Chapel at Ely. Seven lights, the first and last continued up and around the arch (as in that chapel) by a border of quatrefoils. The next two on each side are taken together as one and have in the spandrel an irregular cusped triangle. Over the middle stands a big pointed oval along the border of which run little quatrefoils again. The centre is an octofoiled figure.

There is no Dec style at Mildenhall. Perp the W tower first of all. Angle buttresses with attached shafts carrying little pinnacles (a Somerset motif). Big renewed doorway, big renewed six-light W window with a tier of shields at its foot. Inside on the ground floor the tower has a tunnel-like fan-vault. Above this the unusual motif of a choir gallery open to the nave, with a stone balustrade. Perp also are the arcades between nave and aisles. They have very thin piers with finely moulded shafts and capitals only towards the arch openings. Shafts rise from these right up to the roof. Perp moreover the renewed clerestory windows and the big aisle windows. The N side is richer than the S. There is a little flushwork decoration here and there on battlements with panel decoration in two tiers and with pinnacles. This is the crowning motif of the N porch too. The porch is long and two-storeyed. Niches in the buttresses, shields above the entrance. Vault inside with ridge-ribs, tiercerons, and bosses. On the upper floor was the Lady Chapel (as at Fordham in Cambridgeshire a few miles away). The S porch is simpler. Excellent nave roof of low pitch, with alternating hammerbeams and cambered tie-beams. The depressed arched braces of the tie-beams are traceried, and there is tracery between the queenposts on the tie-beams. Against the hammerbeams big figures of angels. Angels also against the wall-plate. The aisle roofs have hammerbeams too. In the spandrels of those in the N aisle carved scenes of St George and the Dragon, the Baptism of Christ, the Sacrifice of Isaac and the Annunciation. Against the wall-posts figures with demi-figures of angels above them serving as canopies. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, of Purbeck marble with shields in quatrefoils. - NORTH DOOR. With tracery. - PLATE. Cup 1625; Almsdish 1632 ; Cup and Paten 1642; two enamelled Pewter Dishes given in 1648; Flagon given in 1720. - MONUMENT. Sir Henry North d. 1620. Alabaster. Two recumbent effigies. The children kneel below, against the tomb-chest. Background with two black columns, two arches, two small obelisks, and an achievement. - In the churchyard the so-called Read Memorial, in fact the remains of a CHARNEL HOUSE with a chapel of St Michael over. The chapel was endowed in 1387.

MILDENHALL. It has come into a fame it could never have dreamed of in all its centuries, for there was a day on which its name was in every newspaper and on all men’s lips. It is odd that here should sleep the winner of the first Derby, for it was here, where this grave sets us thinking of the speed of a horse, that men set out on a ride compared with which the speed of a Derby winner is that of a tortoise. At Mildenhall began the greatest achievement of speed ever known then, the air race to Australia. This pleasant border town by the River Lark, with miles of firs and fine pine avenues, was the starting-point of the two men who flew across the earth in three days in 1934; they were Charles Scott and Campbell Black and they reached Melbourne from Mildenhall in just under 71 hours. It was the fastest journey across the earth ever known.

The place which thus came into fame in the 20th century goes back as far as the Stone Age, for strewn about its heaths we find worked flints which were the precious tools and weapons of men then. Warren Hill has the quiet graves of Saxons. The church is 13th century, and keeping company with it is an old mill by the river, a fine medieval wooden cross, with a handsome lead roof resting on rough-hewn pillars, homes going back to Tudor days, and 18th century almshouses founded by a Speaker of the House of Commons who helped to secure the Protestant Succession to the throne and gave the world its first fine Shakespeare.

The magnificent church, 700 years old, 170 feet long, and with a tower 120 feet high, is one of the county’s proud possessions, which Cambridgeshire sees from afar as the sun gilds its gay weathercock. The exterior is rich with carving. Above an aisle is a fine panelled parapet; and the buttresses are lavishly decked with canopied niches, of which there are 13 on the buttresses at the east corners alone.

Two graceful porches the church has, the north one 30 feet long (the biggest in Suffolk), with a beautiful vaulted roof with angels and roses on its bosses. Above it is the old schoolroom, with quaint figures carved in the spandrels of its doorway. Under the tower with its fine bold arch is a splendid fan-tracery roof; and a vaulted stone roof covers the 13th century chapel. The nave has lofty 15th century arches, and at either side of the 700-year-old chancel arch are three columns with fine foliage capitals. The piscina and sedilia are about as old as Magna Carta. A striking feature of the 13th century sanctuary window is the adaptation of charming new glass to old architecture. Above the arch of the window are 12 small medallions; between these and the seven slender lights below is an oval like a ring set with jewels.

It is the woodwork for which the church is famous. The pulpit, in memory of a parishioner who was 53 years a churchwarden, is one of the few examples of modern workmanship; the rest is a splendid bequest of the past, instinct with medieval character, work performed in the spirit of some of the old miracle plays, in which religious ecstasy alternates with riotous humour. On the hammerbeams of the 15th century nave roof, one of the finest in the county, are two big angels and some 60 lesser ones, some with books, some with musical instruments, all with outspread wings; even the tiebeams are carved and embattled. The south aisle roof, on which are the swan and antelope of Henry the Fifth, is crowded with ornament; on its fine hammerbeams, in the spandrels and along the cornice, are saints and priests, pelicans and eagles, a dog, a monkey, a squirrel, doves, and a mass of about 160 figures. Finest of all is the north aisle roof. Seven fantastic stone heads carry the splendid, harnmerbeams, between which are saints finely carved with a touch of individual fancy, each secure in the shelter of an angel’s wings. In the spandrels is a gallery of the sublime, the humorous, and the sardonic. Mingled with Bible scenes are a woman in a horned headdress supposed to typify Pride, a comic pig with an astonishing collar, one monkey playing an organ while another blows the bellows, and a demon grasping a dog by its tail.

Many monuments tell the story of six centuries of Mildenhall men. The oldest is that to Sir Richard de Wychforde, the 13th century vicar who built the chancel. His brass portrait is gone, but his tomb is safe below the beautiful window which took shape at his bidding. Under the tower lies Sir Henry de Barton, Lord Mayor in the year after Agincourt, and remembered as having started the lighting of dark benighted London, for it was he who first ordered the people to hang out lights from their houses. Here also rests the builder of the manor house, Sir Henry North; he lies on an alabaster tomb with his wife, both smiling happily. In the chancel lies his grandson Thomas Hanmer, a baronet and an MP at 24 and Speaker at 37. Resisting attempts to win him over to the Pretender, he defended the Protestant Succession, and, when that was made safe by the proclamation of George the First, retired to spend his last 20 years here. Working in his fine library he produced the first nobly printed Shakespeare, making several corrections of errors in the text; his own copy, the Hanmer Fourth Folio, was discovered in 1917 and is in the Bodleian Library.

The church has many monuments to the Bunbury family, which gave it a vicar for over 50 years. Sir Thomas was the winner of the first Derby (with Diomed), and sat in Parliament for 43 years. It was his nephew Sir Henry, soldier, diplomatist, and reformer, whose vote gave the Reform Bill its majority of one, who was chosen for his tact and good nature to communicate to Napoleon the crushing news of the Government’s decision to exile him to St Helena. Sir Henry’s father was the artist Henry William Bunbury, friend of Goldsmith and Reynolds, whose famous “Master Bunbury” is a portrait of the General’s younger brother. Another Bunbury here, a little boy of five who died in 1749, is described as a lovely child who showed great promise. There is one brass portrait, showing the builder of Wamil Hall, a mile away, Sir Henry Warner, wearing armour of the time of James the First, and apparently in the act of putting on his gloves.

Two miles away is the big agricultural village of West Row, with a church built from the materials of the old National School; it has a window in memory of Lawrence Clutterbuck, a curate’s son who gave his life to save a student from drowning.

The place which thus came into fame in the 20th century goes back as far as the Stone Age, for strewn about its heaths we find worked flints which were the precious tools and weapons of men then. Warren Hill has the quiet graves of Saxons. The church is 13th century, and keeping company with it is an old mill by the river, a fine medieval wooden cross, with a handsome lead roof resting on rough-hewn pillars, homes going back to Tudor days, and 18th century almshouses founded by a Speaker of the House of Commons who helped to secure the Protestant Succession to the throne and gave the world its first fine Shakespeare.

The magnificent church, 700 years old, 170 feet long, and with a tower 120 feet high, is one of the county’s proud possessions, which Cambridgeshire sees from afar as the sun gilds its gay weathercock. The exterior is rich with carving. Above an aisle is a fine panelled parapet; and the buttresses are lavishly decked with canopied niches, of which there are 13 on the buttresses at the east corners alone.

Two graceful porches the church has, the north one 30 feet long (the biggest in Suffolk), with a beautiful vaulted roof with angels and roses on its bosses. Above it is the old schoolroom, with quaint figures carved in the spandrels of its doorway. Under the tower with its fine bold arch is a splendid fan-tracery roof; and a vaulted stone roof covers the 13th century chapel. The nave has lofty 15th century arches, and at either side of the 700-year-old chancel arch are three columns with fine foliage capitals. The piscina and sedilia are about as old as Magna Carta. A striking feature of the 13th century sanctuary window is the adaptation of charming new glass to old architecture. Above the arch of the window are 12 small medallions; between these and the seven slender lights below is an oval like a ring set with jewels.

It is the woodwork for which the church is famous. The pulpit, in memory of a parishioner who was 53 years a churchwarden, is one of the few examples of modern workmanship; the rest is a splendid bequest of the past, instinct with medieval character, work performed in the spirit of some of the old miracle plays, in which religious ecstasy alternates with riotous humour. On the hammerbeams of the 15th century nave roof, one of the finest in the county, are two big angels and some 60 lesser ones, some with books, some with musical instruments, all with outspread wings; even the tiebeams are carved and embattled. The south aisle roof, on which are the swan and antelope of Henry the Fifth, is crowded with ornament; on its fine hammerbeams, in the spandrels and along the cornice, are saints and priests, pelicans and eagles, a dog, a monkey, a squirrel, doves, and a mass of about 160 figures. Finest of all is the north aisle roof. Seven fantastic stone heads carry the splendid, harnmerbeams, between which are saints finely carved with a touch of individual fancy, each secure in the shelter of an angel’s wings. In the spandrels is a gallery of the sublime, the humorous, and the sardonic. Mingled with Bible scenes are a woman in a horned headdress supposed to typify Pride, a comic pig with an astonishing collar, one monkey playing an organ while another blows the bellows, and a demon grasping a dog by its tail.

Many monuments tell the story of six centuries of Mildenhall men. The oldest is that to Sir Richard de Wychforde, the 13th century vicar who built the chancel. His brass portrait is gone, but his tomb is safe below the beautiful window which took shape at his bidding. Under the tower lies Sir Henry de Barton, Lord Mayor in the year after Agincourt, and remembered as having started the lighting of dark benighted London, for it was he who first ordered the people to hang out lights from their houses. Here also rests the builder of the manor house, Sir Henry North; he lies on an alabaster tomb with his wife, both smiling happily. In the chancel lies his grandson Thomas Hanmer, a baronet and an MP at 24 and Speaker at 37. Resisting attempts to win him over to the Pretender, he defended the Protestant Succession, and, when that was made safe by the proclamation of George the First, retired to spend his last 20 years here. Working in his fine library he produced the first nobly printed Shakespeare, making several corrections of errors in the text; his own copy, the Hanmer Fourth Folio, was discovered in 1917 and is in the Bodleian Library.

The church has many monuments to the Bunbury family, which gave it a vicar for over 50 years. Sir Thomas was the winner of the first Derby (with Diomed), and sat in Parliament for 43 years. It was his nephew Sir Henry, soldier, diplomatist, and reformer, whose vote gave the Reform Bill its majority of one, who was chosen for his tact and good nature to communicate to Napoleon the crushing news of the Government’s decision to exile him to St Helena. Sir Henry’s father was the artist Henry William Bunbury, friend of Goldsmith and Reynolds, whose famous “Master Bunbury” is a portrait of the General’s younger brother. Another Bunbury here, a little boy of five who died in 1749, is described as a lovely child who showed great promise. There is one brass portrait, showing the builder of Wamil Hall, a mile away, Sir Henry Warner, wearing armour of the time of James the First, and apparently in the act of putting on his gloves.

Two miles away is the big agricultural village of West Row, with a church built from the materials of the old National School; it has a window in memory of Lawrence Clutterbuck, a curate’s son who gave his life to save a student from drowning.

Freckenham, Suffolk

After Soham I decided to visit Mildenhall - this was an unplanned spur of the moment revisit to Ely Cathedral - and on my way spotted St Andrew (LNK) so stopped on the off chance. Basically a very crisp Victorian rebuild, I rather liked it but am not sure I missed much by finding it locked (actually reading Simon Knott's entry I think I missed more than I imagined at the time).

ST ANDREW. Over-restored or rather rebuilt (by Street, 1867). W tower rebuilt 1884. One window with Y-tracery in the vestry, two two-light Perp windows used as a kind of dormer. E window of three stepped lancet lights under one arch, shafted inside, i.e. c. 1300. Arcade with piers of keeled quatrefoil section and arches with one chamfer and one recessed chamfer, i.e. also c. 1300. - Nice Perp canted wagon-roofs in nave and chancel, with bosses. - BENCH ENDS. With poppyheads, some in the form of kneeling figures, very pretty. - SCULPTURE. Alabaster relief from a former altar, a scene from the Life of St Eligius, C15.- PLATE. Elizabethan Cup; Paten 1723.

ST ANDREW. Over-restored or rather rebuilt (by Street, 1867). W tower rebuilt 1884. One window with Y-tracery in the vestry, two two-light Perp windows used as a kind of dormer. E window of three stepped lancet lights under one arch, shafted inside, i.e. c. 1300. Arcade with piers of keeled quatrefoil section and arches with one chamfer and one recessed chamfer, i.e. also c. 1300. - Nice Perp canted wagon-roofs in nave and chancel, with bosses. - BENCH ENDS. With poppyheads, some in the form of kneeling figures, very pretty. - SCULPTURE. Alabaster relief from a former altar, a scene from the Life of St Eligius, C15.- PLATE. Elizabethan Cup; Paten 1723.

FRECKENHAM. It has an ancient windmill, a little bridge, and a group of delightful cottages, and it is proud to possess the oldest blacksmith in Suffolk, a jolly little man with a queer way all his own of shoeing a horse. He is in the church, which is nearly all old though it has a modern tower. Under a single roof are a 13th century chancel and a nave with a 15th century arcade. The chancel has a stone seat below one of its beautiful windows, and the nave an attractive dormer window. In the north aisle roof are 12 wooden corbels with odd faces, and much fine carving watched over by angels. Many of the pews are old oak with fragments of rich carving. There are poppyheads and odd little creatures, animals and birds, a nun praying and a monk on his knees, an angel with a scroll, and a surprising carving of a monkey holding a man upside down.

But it is the blacksmith we come to see, a charming figure in a small alabaster panel found when workmen were repairing the church in 1776. Quite how old he is is not known; he may have been at Freckenham about 600 years. He is thought to be St Eloy, the patron of blacksmiths, and it is said that when he shod a horse he would take away its leg into the smithy, make a shoe for it, and put the leg back, healing the animal by making the sign of the Cross. Here the old legend is quaintly carved for us, with St Eloy holding a horse’s leg on an anvil and a hammer in his hand. Close by is a horse with three legs, its little master wearing a kind of bonnet and looking rather anxious about the missing leg.

But it is the blacksmith we come to see, a charming figure in a small alabaster panel found when workmen were repairing the church in 1776. Quite how old he is is not known; he may have been at Freckenham about 600 years. He is thought to be St Eloy, the patron of blacksmiths, and it is said that when he shod a horse he would take away its leg into the smithy, make a shoe for it, and put the leg back, healing the animal by making the sign of the Cross. Here the old legend is quaintly carved for us, with St Eloy holding a horse’s leg on an anvil and a hammer in his hand. Close by is a horse with three legs, its little master wearing a kind of bonnet and looking rather anxious about the missing leg.

Soham, Cambridgeshire

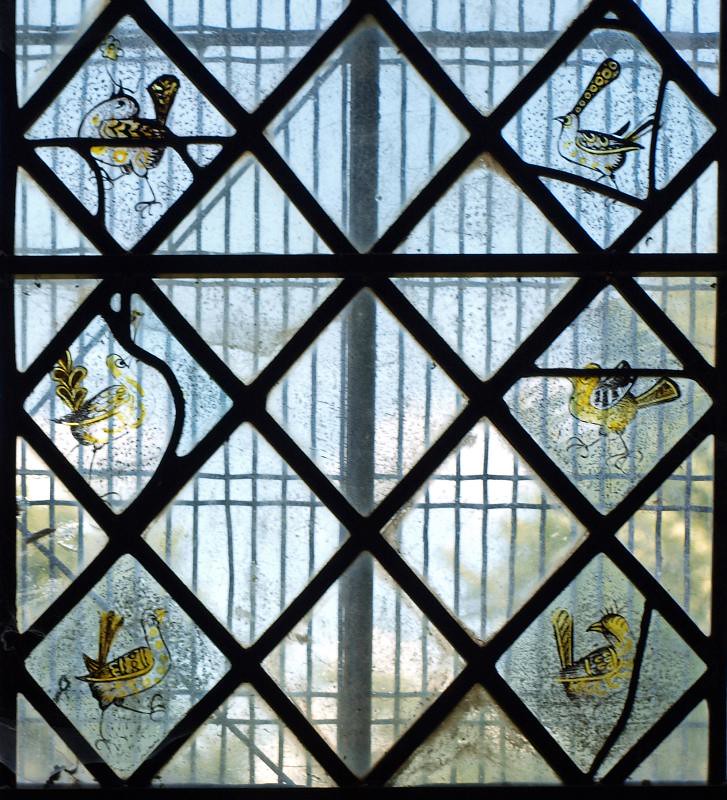

St Andrew, open, is a spectacular barn of a church. Cruciform, although this is not immediately apparent due to the addition of the north aisle and vestry, and built in a very East Anglian style; the exterior is magnificent and the interior holds a wealth of interest from the roof angels in both aisles and nave, some good glass and much damaged poppyheads but my personal favourite was the medieval glass in the vestry.

ST ANDREW. A cathedral was established at Soham by St Felix in the early C7. It was destroyed by the Danes and never rebuilt. Its site is supposed to have been on the E side of the main village street opposite the church. Cruciform church of the late C12. But to the eye, as one approaches the church, it is Perp of a very ambitious kind. The tower and the N view with East Anglian flushwork are what will be remembered. The interior on the other hand is dominated by the earlier remains, especially the four arches of the crossing. They are plain, double-stepped and pointed, except for the W side of the W arch on which Late Norman and Early English decoration is lavished, a three-dimensional kind of crenellation with slanting sides to the merlons and various dog-tooths. Plain and pointed also the arches from the aisles into the transepts, and one-stepped and pointed those of the four-bay arcades. These rest on alternatingly circular and octagonal piers with many-scalloped capitals. The masonry of the transepts is supposed to belong to the same date, and that of the chancel to the C13. Of the C13 also the Double Piscina in the S transept with shafts and arches. The next phase of importance is the Dec style of the early C14. To this belongs the chancel in its present form with a five-light E window that has rich flowing tracery* and the S windows. Dec also the S doorway and the (renewed) S aisle and larger S transept windows. C14 probably the Sedilia too (ogee arches and a framing with a fleuron frieze), and perhaps the addition to the arcade of a W bay separated from the others by a stretch of wall. After that comes the contribution of the Perp, and that is above all the W tower. This is called the Novum Campanile in 1502, when it was probably under construction. It was no doubt a replacement of the crossing-tower. It is of four stages, with diagonal buttresses, a flushwork frieze at the base, a very big four-light W window (renewed), an immensely tall tower arch, and a gorgeous top with stepped battlements and pinnacles decorated with flushwork. At the same time the N transept and N aisle were remodelled with Perp windows, a N chancel chapel was added (arch from the chancel with fleurons) and also a N porch, the latter with flushwork decoration in the battlements and with pinnacles. The porch has inside handsome Perp wall panelling (cf. Isleham, Little Chishall) and a roof on head-corbels. The clerestory also is an addition of the late Middle Ages, and in connexion with its erection the nave received its beautiful roof which is constructed with alternating hammerbeams with figures of angels and castellated tiebeams carrying ten queen-posts each. - ROOD SCREEN, CHANCEL STALLS, CHANCEL PANELLING, and COMMUNION RAIL - all Gothic of 1849 (designed by Bonomi of Durham). - PARCLOSE SCREEN to the N chancel chapel. Perp ; good. Two-light divisions with broad ogee arches and Perp tracery above. Pretty cresting. The uprights are shaped as buttresses. - CHANCEL STALLS with simple misericords; under the tower. - BENCH-ENDS, many, with poppy-heads, also seated beasts, the head of an abbot etc. - PAINTING. Chancel N wall; figure of a bishop; C14. - STAINED GLASS. C15 bits of figures etc. in the Vestry. - MONUMENT. Long ogee-headed recess in the N transept N wall.

* Inside l. and r. of the E window are two niches with tiny bits of flushwork enrichment.

ST ANDREW. A cathedral was established at Soham by St Felix in the early C7. It was destroyed by the Danes and never rebuilt. Its site is supposed to have been on the E side of the main village street opposite the church. Cruciform church of the late C12. But to the eye, as one approaches the church, it is Perp of a very ambitious kind. The tower and the N view with East Anglian flushwork are what will be remembered. The interior on the other hand is dominated by the earlier remains, especially the four arches of the crossing. They are plain, double-stepped and pointed, except for the W side of the W arch on which Late Norman and Early English decoration is lavished, a three-dimensional kind of crenellation with slanting sides to the merlons and various dog-tooths. Plain and pointed also the arches from the aisles into the transepts, and one-stepped and pointed those of the four-bay arcades. These rest on alternatingly circular and octagonal piers with many-scalloped capitals. The masonry of the transepts is supposed to belong to the same date, and that of the chancel to the C13. Of the C13 also the Double Piscina in the S transept with shafts and arches. The next phase of importance is the Dec style of the early C14. To this belongs the chancel in its present form with a five-light E window that has rich flowing tracery* and the S windows. Dec also the S doorway and the (renewed) S aisle and larger S transept windows. C14 probably the Sedilia too (ogee arches and a framing with a fleuron frieze), and perhaps the addition to the arcade of a W bay separated from the others by a stretch of wall. After that comes the contribution of the Perp, and that is above all the W tower. This is called the Novum Campanile in 1502, when it was probably under construction. It was no doubt a replacement of the crossing-tower. It is of four stages, with diagonal buttresses, a flushwork frieze at the base, a very big four-light W window (renewed), an immensely tall tower arch, and a gorgeous top with stepped battlements and pinnacles decorated with flushwork. At the same time the N transept and N aisle were remodelled with Perp windows, a N chancel chapel was added (arch from the chancel with fleurons) and also a N porch, the latter with flushwork decoration in the battlements and with pinnacles. The porch has inside handsome Perp wall panelling (cf. Isleham, Little Chishall) and a roof on head-corbels. The clerestory also is an addition of the late Middle Ages, and in connexion with its erection the nave received its beautiful roof which is constructed with alternating hammerbeams with figures of angels and castellated tiebeams carrying ten queen-posts each. - ROOD SCREEN, CHANCEL STALLS, CHANCEL PANELLING, and COMMUNION RAIL - all Gothic of 1849 (designed by Bonomi of Durham). - PARCLOSE SCREEN to the N chancel chapel. Perp ; good. Two-light divisions with broad ogee arches and Perp tracery above. Pretty cresting. The uprights are shaped as buttresses. - CHANCEL STALLS with simple misericords; under the tower. - BENCH-ENDS, many, with poppy-heads, also seated beasts, the head of an abbot etc. - PAINTING. Chancel N wall; figure of a bishop; C14. - STAINED GLASS. C15 bits of figures etc. in the Vestry. - MONUMENT. Long ogee-headed recess in the N transept N wall.

* Inside l. and r. of the E window are two niches with tiny bits of flushwork enrichment.

SOHAM. It was one of the English cradles of Christianity, where Felix of Burgundy came to found his abbey on high ground above the plain. Here they laid him to rest, and a few years later St Etheldreda founded her abbey at Ely, and both abbeys flourished till both were destroyed by the Danes. Soham Abbey was never raised again, but the little town has a fine view of the cathedral which grew out of Etheldreda’s abbey at Ely, standing on the hill at the end of the five-mile Causeway built to link the two towns soon after the Conquest.

The fruitful orchard land of what was once Soham Mere lies to the west. The sails of a windmill turn at each end of the straggling town and between them lies the splendid church built nearly 800 years ago. Its oldest remains are still its chief glory within, but it is to the 15th century that Soham owes its grand tower, rising above the fenland like a symbol of faith that many waters cannot quench. It rises 100 feet high, with lovely battlements and pinnacles, and looks down on two beautiful medieval porches. The aisles have cornices carved with roses, and there are heads at the south doorway. There is an impressive array of arches inside, four of them believed to have supported the central tower of the 12th century church. The western arch has rich mouldings and capitals of that period, and most of the simpler arches of the nave are of the same age. The tower arch soars impressively, and an arch of the 15th century, leading into a chapel, has two rows of flowers in its mouldings, embattled capitals, and grotesque animals on each side. The chancel has 13th century walls, the south transept has a 13th century piscina, but the richly carved sedilia is 14th. A brave array of angels, sitting and kneeling, praying and holding shields, looks down from the grand old roof.

In one of the chapels, to which we come by an ancient door with iron bars and a massive lock, is an old stone altar, and medieval glass with angels, birds, and flowers. Among a wealth of ancient woodwork in the church is a 15th century screen, its tracery tipped with roses, animals, and grotesque faces; an eagle and a queer man are peeping out above the entrance. There are 15th century benches with carved heads on which is an angel, a bishop, and a flying lizard, and on some 600-year-old stalls in the tower are carved seats with the quaint fancies of the medieval craftsmen. On one of the walls is an old painting of a bishop, and hidden behind the organ is the 16th century monument of Edward Bernes, showing his 15 children kneeling; he and his wife are lost, An inscription in the chancel tells of John Cyprian Rust, “scholar and friend of children,” who shepherded his flock here for 53 years.

In the churchyard lies a very old man whose inscription says curiously, “Dr Ward, whom you knew well before, was kind to his neighbours and good to the poor,” and not far from him is the grave of Elizabeth D’Aye, unknown to most of those who come into this churchyard, yet a woman of much interest, for her mother was the only grown-up daughter of Cromwell’s best son, Henry. Elizabeth had come down in the world. Her mother, Elizabeth Cromwell, had married an officer in the army, William Russell of Fordham, who lived far beyond his income, kept a coach and six horses, and gathered so many creditors about him that it was said to be fortunate that he died. His widow, so far from trying to retrieve the shattered fortunes of her family, struggled to keep up appearances, and it is recorded that she took as many of her 13 children as she could and went up to London, where she died of smallpox caught by keeping the hair of two of her daughters who had died from it.

Her daughter Elizabeth married Robert D’Aye of Soham, who also spent a good fortune, and was so reduced that he died in the workhouse. Richard Cromwell’s daughter appears to have come to widow D’Aye’s assistance, but she died in the grip of poverty, leaving behind her still another Elizabeth, who married the village shoemaker of Soham, a man of honesty and good sense who rose to be a high-constable. Well may the biographer of the House of Cromwell be moved by the thought of his descendants begging their daily bread. “Oh, Oliver,” says he, “if you could have seen that the gratification of your ambition could not prevent your descendants in the second and third generation from falling into poverty, you would surely have sacrificed fewer lives to that idol. How much are they to be pitied!”

There was born at Soham in 1748 a leather-seller‘s son named James Chambers, who must have broken his father’s heart by choosing evil ways and living the life of a ne’er-do-well while trying to be a poet. He lived to be nearly 80, when he died at Stradbroke, and for most of his life he appears to have been a roaming gipsy, making acrostics of people’s names if they would give him a meal. He wrote some of his verses in Soham workhouse, but none of them are to be matched with the fine work that has come from many of these houses of adversity. There are references to him in old books and papers, but he has been forgotten as a good-for-nothing, and the best reference we have found to him was written by Mr Cordy of Worlingworth in Suffolk:

A lonely wanderer he, whose squalid form

Bore the rude peltings of the wintry storm:

Yet Heaven, to cheer him as he passed along,

Infused in life’s sour cup the sweets of song.

Mr Cordy made an appeal for him and found him a cottage, which was furnished so as to encourage him with his poems. But it was no use; in a month or two he was off again, preferring a bed of straw to a couch of down.

Flickr.

The fruitful orchard land of what was once Soham Mere lies to the west. The sails of a windmill turn at each end of the straggling town and between them lies the splendid church built nearly 800 years ago. Its oldest remains are still its chief glory within, but it is to the 15th century that Soham owes its grand tower, rising above the fenland like a symbol of faith that many waters cannot quench. It rises 100 feet high, with lovely battlements and pinnacles, and looks down on two beautiful medieval porches. The aisles have cornices carved with roses, and there are heads at the south doorway. There is an impressive array of arches inside, four of them believed to have supported the central tower of the 12th century church. The western arch has rich mouldings and capitals of that period, and most of the simpler arches of the nave are of the same age. The tower arch soars impressively, and an arch of the 15th century, leading into a chapel, has two rows of flowers in its mouldings, embattled capitals, and grotesque animals on each side. The chancel has 13th century walls, the south transept has a 13th century piscina, but the richly carved sedilia is 14th. A brave array of angels, sitting and kneeling, praying and holding shields, looks down from the grand old roof.

In one of the chapels, to which we come by an ancient door with iron bars and a massive lock, is an old stone altar, and medieval glass with angels, birds, and flowers. Among a wealth of ancient woodwork in the church is a 15th century screen, its tracery tipped with roses, animals, and grotesque faces; an eagle and a queer man are peeping out above the entrance. There are 15th century benches with carved heads on which is an angel, a bishop, and a flying lizard, and on some 600-year-old stalls in the tower are carved seats with the quaint fancies of the medieval craftsmen. On one of the walls is an old painting of a bishop, and hidden behind the organ is the 16th century monument of Edward Bernes, showing his 15 children kneeling; he and his wife are lost, An inscription in the chancel tells of John Cyprian Rust, “scholar and friend of children,” who shepherded his flock here for 53 years.

In the churchyard lies a very old man whose inscription says curiously, “Dr Ward, whom you knew well before, was kind to his neighbours and good to the poor,” and not far from him is the grave of Elizabeth D’Aye, unknown to most of those who come into this churchyard, yet a woman of much interest, for her mother was the only grown-up daughter of Cromwell’s best son, Henry. Elizabeth had come down in the world. Her mother, Elizabeth Cromwell, had married an officer in the army, William Russell of Fordham, who lived far beyond his income, kept a coach and six horses, and gathered so many creditors about him that it was said to be fortunate that he died. His widow, so far from trying to retrieve the shattered fortunes of her family, struggled to keep up appearances, and it is recorded that she took as many of her 13 children as she could and went up to London, where she died of smallpox caught by keeping the hair of two of her daughters who had died from it.

Her daughter Elizabeth married Robert D’Aye of Soham, who also spent a good fortune, and was so reduced that he died in the workhouse. Richard Cromwell’s daughter appears to have come to widow D’Aye’s assistance, but she died in the grip of poverty, leaving behind her still another Elizabeth, who married the village shoemaker of Soham, a man of honesty and good sense who rose to be a high-constable. Well may the biographer of the House of Cromwell be moved by the thought of his descendants begging their daily bread. “Oh, Oliver,” says he, “if you could have seen that the gratification of your ambition could not prevent your descendants in the second and third generation from falling into poverty, you would surely have sacrificed fewer lives to that idol. How much are they to be pitied!”

There was born at Soham in 1748 a leather-seller‘s son named James Chambers, who must have broken his father’s heart by choosing evil ways and living the life of a ne’er-do-well while trying to be a poet. He lived to be nearly 80, when he died at Stradbroke, and for most of his life he appears to have been a roaming gipsy, making acrostics of people’s names if they would give him a meal. He wrote some of his verses in Soham workhouse, but none of them are to be matched with the fine work that has come from many of these houses of adversity. There are references to him in old books and papers, but he has been forgotten as a good-for-nothing, and the best reference we have found to him was written by Mr Cordy of Worlingworth in Suffolk:

A lonely wanderer he, whose squalid form

Bore the rude peltings of the wintry storm:

Yet Heaven, to cheer him as he passed along,

Infused in life’s sour cup the sweets of song.

Mr Cordy made an appeal for him and found him a cottage, which was furnished so as to encourage him with his poems. But it was no use; in a month or two he was off again, preferring a bed of straw to a couch of down.

Flickr.

St Mary, Ely, Cambridgeshire

Returning to Ely Cathedral to record the misericords I missed, which led to a further 80 pictures of various monuments, glass and other bits I'd missed first time round, I had time to visit St Mary (LNK) and found a rather disappointing Victorian restoration. Pevsner says that "the inside has more of interest than the outside" but I'm not sure that, based purely on his entry, that the interior would lift this church out of the pedestrian category - although the N door sounds good.

ST MARY. The inside has more of interest than the outside. It represents the building begun and dedicated by Bishop Eustace (1198-1215). A long and wide Transitional nave with seven bays, divided by slim circular piers with scalloped capitals. The arches are pointed and finely moulded. The clerestory was added or renewed in the C15. But to the earlier period belongs the excellent N doorway which is no doubt the work of the cathedral and monastery workshop. The arch here is still round and has in two orders a decoration still essentially a three-dimensional variety of the zigzag motif, but the arch orders rest on columns with shaftrings and stiff-leaf capitals (cf. Deanery, i.e. Infirmary Chapel). E.E. chancel with lancet windows, except for the first from the W which are on the S side Dec, on the N Perp. Perp also the E window. The W steeple belongs to the C14, see the tower arch into the nave with its characteristic mouldings, the W door, the bell-openings and especially the spire with two tiers of dormers, one near the foot, the other near the top. Pinnacles on the corners of the tower-top; no battlements.

St Mary’s church, begun in 1198, has a 14th century tower and spire, and windows of all three medieval centuries, filling the interior with light, some of them shining with rich glass. The long nave arcades of seven bays have pointed 13th century arches, and tall pillars with scalloped capitals marking the passing of the Norman style. A fine doorway of this time, sheltered by the north porch, has an arch with elaborate carving of zigzag under a hood, and clustered shafts with capitals of graceful foliage. The blocked south doorway has lost its shafts after 750 years, but keeps its arch of zigzag and its leafy capitals. The old priest’s seat in the chancel has a trefoiled arch and there is a fine little double piscina in the south chapel, which is entered by a low medieval arcade. The triple lancet of its east window has the Crucifixion and Our Lord in Glory, St Edmund and his martyrdom, and St Etheldreda with a fine picture of the cathedral. The east window of the chancel has glass showing the Nativity and the Shepherds. Another window has Our Lord Risen, with blue-winged angels; and one in memory of the men who fell in the Great War has figures of St George, the Archangel Michael, and Earldorman Brihtnoth as a warrior. St George is fighting the dragon with the princess looking on. Below Brihtnoth is a fine picture of the boat bringing his body to Ely, rowed by nuns, candles burning by his bier. A big broken font is in the churchyard, and on a buttress of the tower is a tablet reminding us of the Ely riots, with the names of five men executed in June 1816 “for divers robberies.”

Perhaps we should think much more of St Mary’s if it were not in the shadow of Ely Cathedral; it would be a superb building indeed which could endure such rivalry. A rare town it would be, also, which could compare with this, a gem in England’s coronet.

Flickr.

ST MARY. The inside has more of interest than the outside. It represents the building begun and dedicated by Bishop Eustace (1198-1215). A long and wide Transitional nave with seven bays, divided by slim circular piers with scalloped capitals. The arches are pointed and finely moulded. The clerestory was added or renewed in the C15. But to the earlier period belongs the excellent N doorway which is no doubt the work of the cathedral and monastery workshop. The arch here is still round and has in two orders a decoration still essentially a three-dimensional variety of the zigzag motif, but the arch orders rest on columns with shaftrings and stiff-leaf capitals (cf. Deanery, i.e. Infirmary Chapel). E.E. chancel with lancet windows, except for the first from the W which are on the S side Dec, on the N Perp. Perp also the E window. The W steeple belongs to the C14, see the tower arch into the nave with its characteristic mouldings, the W door, the bell-openings and especially the spire with two tiers of dormers, one near the foot, the other near the top. Pinnacles on the corners of the tower-top; no battlements.

Nearer the cathedral is another timbered house, and between them

stands St Mary’s church, with its spire rising above the long low roof;

it is reached by a dainty avenue of almond trees across the sward. Below

the vicarage are the almshouses, with gables and a tower, standing

round three sides of lawn and garden.

St Mary’s church, begun in 1198, has a 14th century tower and spire, and windows of all three medieval centuries, filling the interior with light, some of them shining with rich glass. The long nave arcades of seven bays have pointed 13th century arches, and tall pillars with scalloped capitals marking the passing of the Norman style. A fine doorway of this time, sheltered by the north porch, has an arch with elaborate carving of zigzag under a hood, and clustered shafts with capitals of graceful foliage. The blocked south doorway has lost its shafts after 750 years, but keeps its arch of zigzag and its leafy capitals. The old priest’s seat in the chancel has a trefoiled arch and there is a fine little double piscina in the south chapel, which is entered by a low medieval arcade. The triple lancet of its east window has the Crucifixion and Our Lord in Glory, St Edmund and his martyrdom, and St Etheldreda with a fine picture of the cathedral. The east window of the chancel has glass showing the Nativity and the Shepherds. Another window has Our Lord Risen, with blue-winged angels; and one in memory of the men who fell in the Great War has figures of St George, the Archangel Michael, and Earldorman Brihtnoth as a warrior. St George is fighting the dragon with the princess looking on. Below Brihtnoth is a fine picture of the boat bringing his body to Ely, rowed by nuns, candles burning by his bier. A big broken font is in the churchyard, and on a buttress of the tower is a tablet reminding us of the Ely riots, with the names of five men executed in June 1816 “for divers robberies.”

Perhaps we should think much more of St Mary’s if it were not in the shadow of Ely Cathedral; it would be a superb building indeed which could endure such rivalry. A rare town it would be, also, which could compare with this, a gem in England’s coronet.

Flickr.

Wednesday, 18 June 2014

Hemingford Abbots, Huntingdon

A fine exterior and an excellent location belies a rather dull interior. The plaster stripped nave walls left me cold but I liked the Hildesley glass in the north aisle and the nave roof Angels were good.

I rather wish I'd found Hemingford Grey.

ST MARGARET. Of brown cobbles. W tower with clasping buttresses with chamfers towards the middles of the sides and a recessed spire with two bands and two tiers of lucarnes in alternating directions. Interesting N aisle with windows and doorway of c.1300. All three windows are of two lights and straight-headed, which is remarkable, and the E window is just as remarkable, provided it is not interfered with. The chancel is of yellow brick, probably of c.1800. The interior has arcades of three bays (standard elements) plus a truncated fourth into which the tower now cuts. The E bay represents a former crossing. This is evident from the thicker octagonal piers, the half-arches, i.e. flying buttresses, across the aisles, and the thickening of the upper nave walls. Another disturbance in the clerestory walls is the replacement of two-light by three-light windows. Fine decorated rood-bay of the nave roof. Decorated bosses also in the N aisle roof. The S porch entrance is E.E. Could it belong to the date of the arcades, or must it be earlier? And is it re-set? - STAINED GLASS. In the N aisle E window good C18 heraldic glass. - In a N aisle window glass by Tower, of 1928, incredibly reactionary.- PLATE. Salver on foot of Britannia metal, 1719-20; two Cups and a Flagon, 1795-6; Paten on foot, 1800-1. - MONUMENTS. Joshua Barnes d. 1712. Baldacchino above the inscription; putto-heads and palm-fronds at the bottom. He was Regius Professor of Greek; so the inscription is partly in Greek. - Jacob Maxey d. 1710. Tablet with a little bust on top.

I rather wish I'd found Hemingford Grey.

ST MARGARET. Of brown cobbles. W tower with clasping buttresses with chamfers towards the middles of the sides and a recessed spire with two bands and two tiers of lucarnes in alternating directions. Interesting N aisle with windows and doorway of c.1300. All three windows are of two lights and straight-headed, which is remarkable, and the E window is just as remarkable, provided it is not interfered with. The chancel is of yellow brick, probably of c.1800. The interior has arcades of three bays (standard elements) plus a truncated fourth into which the tower now cuts. The E bay represents a former crossing. This is evident from the thicker octagonal piers, the half-arches, i.e. flying buttresses, across the aisles, and the thickening of the upper nave walls. Another disturbance in the clerestory walls is the replacement of two-light by three-light windows. Fine decorated rood-bay of the nave roof. Decorated bosses also in the N aisle roof. The S porch entrance is E.E. Could it belong to the date of the arcades, or must it be earlier? And is it re-set? - STAINED GLASS. In the N aisle E window good C18 heraldic glass. - In a N aisle window glass by Tower, of 1928, incredibly reactionary.- PLATE. Salver on foot of Britannia metal, 1719-20; two Cups and a Flagon, 1795-6; Paten on foot, 1800-1. - MONUMENTS. Joshua Barnes d. 1712. Baldacchino above the inscription; putto-heads and palm-fronds at the bottom. He was Regius Professor of Greek; so the inscription is partly in Greek. - Jacob Maxey d. 1710. Tablet with a little bust on top.

HEMINGFORD ABBOTS. Who can forget its lovely square, the old thatched barns, the white houses, and the green river bank? It was the Hemingford of the abbots of Ramsey as distinguished from the Hemingford which belonged to the Greys. It has spacious meadows by the Ouse, a fine park, two lakes, and a heronry. Some of its cottages were here in Cromwell’s day, and we found here two descendants of Cromwell’s sister Jane, Mrs Ivatt and her daughter. The medieval clerestoried windows of the 13th century church are a joy to see, and its carved and painted roof is a splendid piece of Tudor England, with ten angels holding musical instruments and 12 figures with shields. Some of the small robed figures have long hair and look very quaint. The inscription on one of the tie-beams can still be seen, and it reads: “Pray for Wyllm basele and for hys wyvs.” There is a painting of St Christopher fading on the walls after 500 years. The fine 14th century tower (the base of which juts into the nave) is later than the nave and takes the place of the old central tower. It has a lofty spire seen far off. By the south door are two sundials. A stone coffin has been brought indoors from a field near by; with it was a vase found when the coffin was opened. We noticed a curious thing in the rectors list here, for the first rector gloried in the name of Aristotle.

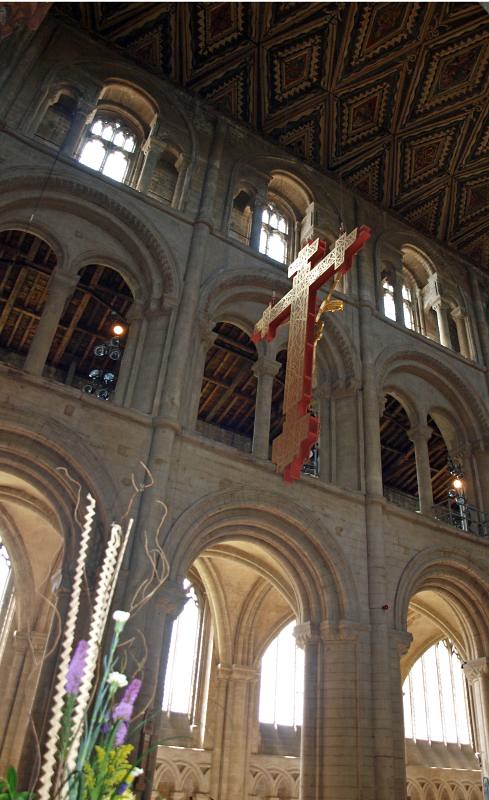

Peterborough, Cambridgeshire - St John

St John (locked no keyholder) is a stone's throw west of the cathedral's gatehouse and is a gem. Sitting, rather oddly, in the middle of the Westgate shopping precinct the perfectly symetrical N and S aisles lend dignity to this rather misplaced church - I assume the precinct was built before town planning was thought of.