It's unusual to decide that the second church you've visited on a trip is your church of the day but that's what happened at the Chapel of St Nicholas. Ignore the hideous Victorian rendered tower and luxuriate in the splendid flintwork, Tyrell carvings and the stunning setting; this is nigh on perfect and then you go inside. Due to the lack of stained glass this is an extraordinarily light interior, think Tilty in Essex, the airy feeling is helped by the light wood pews and cream painted reading desk and pulpit.

Simply put this is a stunning interior and then on top of all that the five light east window is a fantastic mosaic of medieval fragments. Nothing would top this building today, or so I thought.

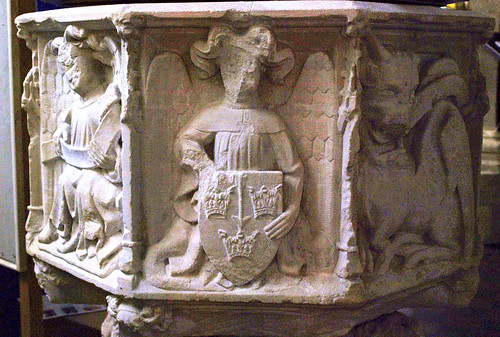

CHAPEL OF ST NICHOLAS. The private chapel of Sir James Tyrell, who died in 1502. Built probably c. 1483. The chapel was close to a mansion of which not a trace is left. The plastered C19 W tower spoils what would otherwise be a singularly perfect piece of late medieval Suffolk architecture. The building is all of a piece, nave and chancel and a curious N annexe. This has a fireplace in its N wall, and it has been assumed that originally it was the chaplain’s dwelling. The wall behind the fireplace is treated as a dummy bay window. It is canted, and the one-light, three-light, one-light rhythm with transoms is all made up of flushwork. W entrance to the room with inscription: ‘Pray for Sir Jamys Tirell and dame Ann his wife.’ The Tyrell knot appears everywhere in the flushwork decoration, which is generously applied to walls, buttresses, etc. The composition of N and S doorways is identical, and they are charming pieces too. Whereas the other windows are of three lights and transomed, there are here four lights and the lower part of the middle two is taken up by the doorway. The lower parts to its 1. and r. are again flushwork dummies, and in the upper parts flushwork also is inserted between the two l. and the two r. lights. E wall with polygonal buttresses. Five-light E window. The interior is as translucent as a glasshouse. What effect the original glass must have had, of which fragments and five small figures remain in the 12 window, it is hard to guess. - BENCH. One original kneeling-bench; the end is of quite exceptional, very simple shape, and has the Tyrell knot. Twisted-leaf frieze along the back of the seat. - PLATE. Two

Patens 1704; Cup 1712.

GIPPING. One of the blackest deeds in human annals must always be remembered here, yet Gipping has much charm. It gives its name to a river; it has a Saxon burial-place near by; and close to the green stands a fairy-story cottage, with dormer windows in a steep thatched roof.

We come to the church by a wooden footbridge in the shade of a yew, pausing to admire its effective ornamentation in flint and stone. The tower is modern, but most of the building is 14th century. There is a very old font bowl, but the great sight is the old glass filling the east window, which has beautifully coloured figures of Mary and John (from a Crucifixion), an abbot, a knight, and a lady. With them are parts of golden canopies and many glowing fragments. This window has been reconstructed in our time with the help of a grant from the Pilgrim Trust.

Yet the most stirring thing in the church is an inscription over the vestry doorway outside, asking us to pray for Sir James Tyrrell and Dame Anne his wife. We cannot look at it without feeling that he needs all the prayers we can give him, for it was he who carried out the murder of the little princes in the Tower, which Shakespeare calls

The most arch act of piteous massacre

That ever yet this land was guilty of.

The order came from the bloodstained Richard the Third, and was refused by Sir Robert Brackenbury, who passed it on to James Tyrrell. To him were given the keys of the Tower for one night, and in his presence two rutfians did a thing which has become an everlasting shame to England. There is a tradition that the vestry was built as a chapel by Tyrrell in remorse for his crime; he certainly settled here before he died a traitor’s death.

Three Tyrrells stand out in history, all of the same family: Sir Walter, who slew Rufus; Sir John, who fought at Agincourt and was Speaker of the House of Commons; and Sir John’s grandson Sir James, murderer of the princes.

On the death of Edward the Fourth in April 1483, his elder son, aged 13, became Edward the Fifth. Three weeks later he was in the hands of Richard and sent to the Tower, where he was joined by his younger brother, Duke of York. On June 26 Richard got himself declared king, but with the princes alive his position was insecure, so, while lying at Warwick Castle, he sent word to Sir Robert Brackenbury, Lieutenant of the Tower, hinting at his foul intent. Brackenbury received the message while on his knees at prayer, and indignantly refused to do the deed.

Sir James Tyrrell was more pliant. Hearing that Brackenbury was obdurate, Richard went in the middle of the night into a room where Tyrrell, his Master of the Horse, lay on a pallet bed. Tyrrell needed no urging. With the dawn he was riding to London bearing a royal order that Brackenbury should deliver to him the keys and passwords of the Tower for one night. With Tyrrell rode two brutal knaves, John Dighton and Miles Forrest, who suffocated the sleeping boys while Tyrrell kept guard at the foot of the stairs.

Tyrrell lived on in profit and honour, fought at Bosworth Field, served Henry the Seventh, but at last came himself to the Tower, and before his execution confessed the whole story.

The skeletons of the victims were found during reconstructions at the Tower in the time of Charles the Second, and were interred in the chapel of Henry the Seventh in Westminster Abbey.