I was slightly irritated to find, having forked out the £10 entrance fee, that the chapel was closed for, I assume, an upcoming graduation ceremony. A week later I returned to find the notice board outside the gatehouse had a "Chapel closed today" notice which made it worse!*

Having said that the antechapel is full of interest and resulted in 98 photos on it's own. To be honest I didn't particularly warm to St John's, it all felt rather industrial [I hadn't read Pevsner when I wrote this]. When I return for Trinity and Peterhouse I'll consider paying out again but will make sure the chapel itself is open.

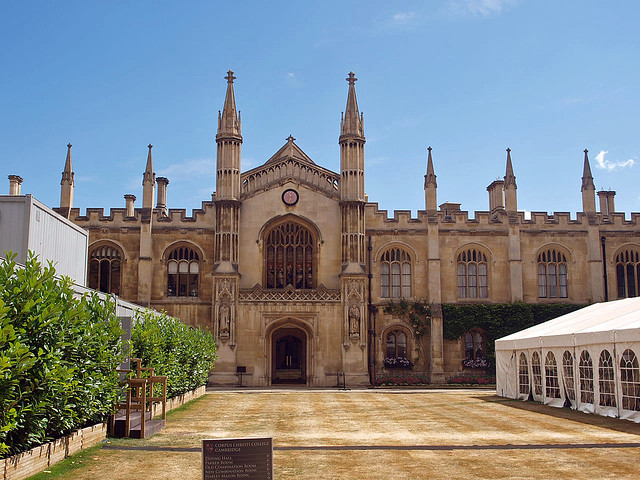

The CHAPEL was built from 1863 to 1869 by Scott. On the choice of shape and style he wrote in his memorandum to the college: ‘In selecting the style to be followed . . . we may either adopt the best variety of pointed architecture, irrespective of the history of the College, or we may choose between the date of the College itself and that of the preceding establishment. . . . Had the date of the College itself coincided with that of the highest perfection of pointed architecture, there would have been no room left for doubt; as, however, this was not the case, it is satisfactory that such a coincidence does exist as regards the date of the older chapel, which belongs to the latter half of the thirteenth century. I have therefore adopted that period as the groundwork of my design. The type of Chapel I have chosen is that so frequent at Oxford, having an ante-chapel placed in a transverse position, something like a transept, at the west end. . . . In adopting this type I have not been actuated by my desire to introduce an Oxford model, but have done so because it happens to be particularly well suited to the position.’ So the chapel has its W transept and a tall square-topped crossing tower on the meeting place between this and the chapel proper. The transept is made two bays wide to allow for a tall pier on the N and one on the S as additional supports for the tower. Pershore gave the style for the external details of the tower.* For the chapel altogether Scott had remembered the Sainte Chapelle in Paris with its polygonal apse. The apse faces St John’s Street, and it is chiefly this apsidal form which will not join up with the rectangular shapes of the other buildings and the court that makes the chapel appear so alien in the community of collegiate buildings. But Scott and his contemporaries visualized their buildings in isolation. They did not believe in that moderate degree of uniformity or at least accepted relationship without which no precinctual composition is possible. In plan the gap in the E front of the college is especially painful.

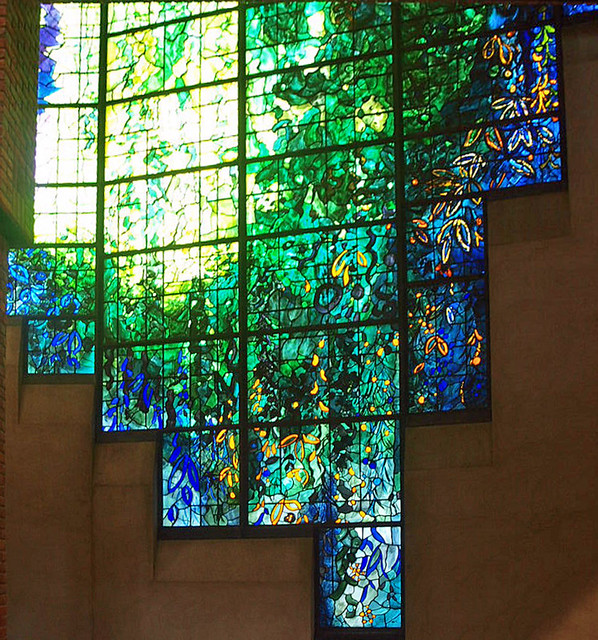

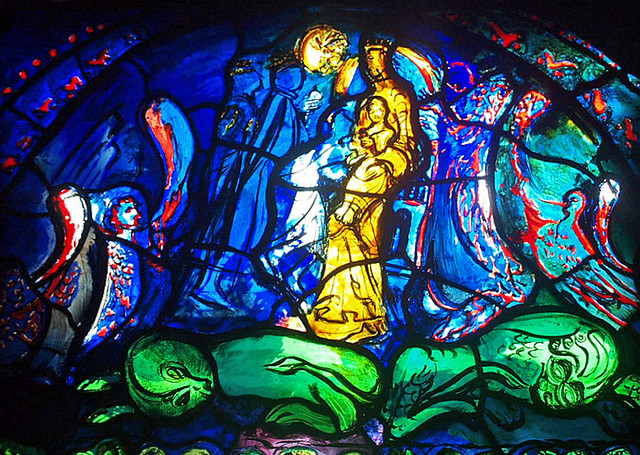

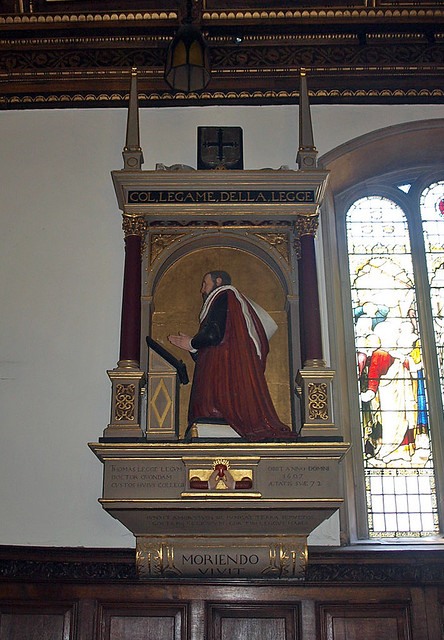

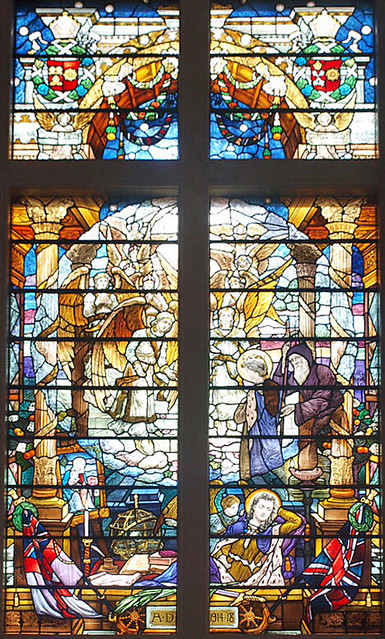

The chapel is 193 ft long, the tower 163 ft high. The building is of good Ancaster stone, with tall pointed windows. The tracery imitates 1300 and the blank arcading inside the apse is of C13 style. The piers of the crossing are of Peterhead red granite. Lizard serpentine and various British marbles are also used - again an example of how the Victorians wished to isolate individual motifs. The stone carving was done by Farmer & Brindley in London, the wood carving by Rattee & Kett in Cambridge. In front of the altar fine PAVING with allegorical figures and scenes, in a subdued Italian style. Good work; who may the designer be? To the r. of the altar is the PISCINA, behind Scott’s arcading. This is original work of the later C13 from the old chapel. With its intersected round-headed arches it is very similar to the more ornate Piscina in Jesus College Chapel. - ORGAN FRONT. 1890 by Oldrid Scott. - STALLS. Twenty-two on each side are of 1516. - PAINTING. Large Pieta by Anton Raphael Mengs, in the S transept. - STAINED GLASS. Mostly by Clayton & Bell, with their typical dark browns, reds, and whites. N transept Blunt Window by Hardman, c. 1869; Tatham window by Wailes (more colourful and more strident), c. 1869 (TK). - MONUMENTS. Fisher Chantry. Of Bishop Fisher’s chantry chapel one of the entrance arches has been re-erected in the S wall of the S transept. The other two are copies. - Hugh Ashton d. 1522. The tomb-chest is opened below so as to allow a corpse to be seen inside. On the chest Ashton’s recumbent effigy. Panelled four-centred arch and straight cresting above. The iron railings seem to be contemporary. – John Smith d. 1715, tablet by E. Stanton. - Henry Kirke White, died as an undergraduate 1806, with fine head in medallion, by Chantrey. - Charles Fox Townshend, died as an undergraduate 1817, bust by Chantrey. – James Wood, seated statue by Baily, 1843.- War Memorial 1914-18, designed by H. M. Fletcher.

* On the W face fragment of the E window of the old chapel.

Its story takes us back to the oldest foundation in Cambridge, for it stands on the site of a small hospital for the sick, founded about 1135 by Henry Frost and managed by Augustinian friars. It was here that Hugh de Balsham tried to establish his college in 1280, but the experiment met with no success, and a few years later the bishop founded Peterhouse for his secular scholars. The hospital carried on till the 16th century, when Margaret Beaufort, mother of our Tudor dynasty, founded a college in its place. As Henry the Eighth seized most of her bequest for himself, the college was not opened till seven years after her death, but St John’s is now surpassed only by Trinity in size and wealth.

Its original buildings were destroyed last century to make way for the chapel built by Sir Gilbert Scott, a splendid addition in stone to a delightful court which for the rest is of red brick, keeping much old work in the ranges east and west, and the foundations of the old chapel laid bare in its gracious lawn.

We come to it from St John's Street by the loveliest of all the gateway-towers in Cambridge, Tudor but much restored. The turrets fronting the street have been made afresh and windows framed in new stone; but to replace bricks mouldered beyond repair old cottages were bought and every fragment fit to be used again was numbered. The great stone panel over the archway, gleaming with colour and gold, has the arms of France and England supported by the heraldic antelopes of Beaufort. Beneath the shield is the Tudor rose; to the left and right of it the rose and portcullis are under crowns; the ground is dotted with marguerites and other flowers, and over a band of flowers is a charming cornice of vine. Between the windows above is a statue of St John under a lovely canopy, set here in 1662. The archway has a roof of exquisite fan tracery enriched with two bosses - a red rose and a portcullis among marguerites; and its magnificent old door is carved with linenfold.

South of the gateway in this eastern range was the old library. In the fine old west range of mottled brick, with a statue of Lady Margaret as high up as the battlements, are the kitchen and the buttery, and the beautiful hall. Through a doorway adorned with the rose and portcullis we come to the second court, a truly illustrious example of the brickwork of Elizabethan builders, and the gift of Mary Cavendish, wife of the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, whose statue is on the turreted gateway in its west range. The north range of this court was originally the Master’s gallery; its transformation into the Combination Room, one of the finest of its kind, was one of the alterations by Sir Gilbert Scott.

The first portion of the small third court to be erected was the present Library, an extension towards the river from the Master’s gallery. Built in 1624, it has traceried windows giving it something of the appearance of a Gothic chapel; it is well furnished with the old bookcases and desks, and is entered by a richly carved door, guarding among its treasures examples of early printing and valuable manuscripts. The quadrangle was completed in the time of Charles the Second. Through one of the archways of its cloistered west range we come to an exquisite thing, a bridge like a stone screen spanning the river, its window tracery filled with iron grilles, its parapets embattled and pinnacled. Known as the Bridge of Sighs (probably because it has the same delicate beauty as the Venice Bridge of Sighs), it was built last century as an approach to the long narrow court on the other side of the river, its buildings rising impressively on three sides, with many windows in their high embattled walls, and an imposing north entrance with turrets and a tower with a lantern. The fourth side of this New Court is a lofty vaulted cloister, of which the archway leading to the Backs has beautiful fan tracery with a great pendant boss. From this bank of the stream the view of the old buildings of the college and their setting is enchanting; curved gables crown the river front, near by is the old balustraded bridge to which comes John’s Lane, and beyond are the gables of Trinity and the turrets of King’s College Chapel. On a pier of the cloister in the Library Court are two flood marks of the height to which the river rose in 1762 and 1795.

St John’s may well be proud of its hall, its chapel, and the Combination Room. Spacious and stately, the hall has panelling of fine old linenfold with a cornice of leaves and flowers, the screen behind the high table magnificent with richly carved pilasters, coved cornice, and a great coat-of-arms reaching the roof. Much of the hammerbeam roof is old, and in the gallery of fine portraits are many fine folk. Looking down on the hall she never saw, though she planned it, is Margaret Beaufort in white kennel headdress, kneeling at a desk under a striking canopy of rich brocade glowing with dull gold. It is a noble group of men that keeps her company. We see the great John Fisher, whose devotion persuaded Lady Margaret so that all the opposition to the fulfilling of his dream of St John’s was overcome; Thomas Wentworth, the tragic Earl of Strafford, who here started that career which ended on Tower Hill; William Wilberforce, who saved the slaves; Roger Ascham, Greek reader at St John’s and scholar at the court of Queen Elizabeth; the immortal Ben Jonson and the inimitable Robert Herrick; Lord Palmerston and Viscount Castlereagh; and our noble Wordsworth, who lodged as an undergraduate in dark chambers by the kitchen, as we read in an inscription in one of the windows. With these portraits hang those of Matthew Prior (painted by Rigaud); Richard Bentley, scholar and critic; Sir John Herschel and John Couch Adams, the astronomers (of whom there are also busts); William Cecil, Queen Elizabeth’s great Lord Burleigh; Henry Kirke White, Edward Villiers, and Sir Noah Thomas, whose portrait is by Romney.

The fascinating Combination Room has a rich plaster ceiling moulded by Italian craftsmen, and panelled walls on which, on high days and holidays, the silver sconces twinkle with the light of a hundred candles. There are a score of especially fine Chippendale chairs, two fine carved chests, and two beautiful fireplaces, one with inlaid pictorial panels brought to this princely gallery from a Cambridge house. Old glass in the oriel window shows Henrietta Maria, whose marriage contract was signed in this room, and among the portraits of the college’s great people is Margaret Beaufort herself. On the stairway to the room is a portrait of Samuel Butler painted by himself, and a collection of his paintings and sketches is in the Green Room by the lobby.

There is architectural splendour in the style of the 14th century in Sir Gilbert Scott’s chapel, with its arcaded walls, open parapets, pinnacled buttresses with statues in canopied niches, and the massive tower rising to about 160 feet, saints in niches adorning its handsome belfry. The tower rests on fine arches with clustered pillars, and its roof inside is 95 feet above the floor. In a wall of the antechapel is one of the original arches which led to Bishop Fisher’s chantry; his head is peeping out of the tracery. Another of the four chantries in the old chapel was that of Hugh Ashton, comptroller of Lady Margaret’s household, and his arresting monument is here for us to see. He lies in his robes, a coloured figure at prayer, and under the table on which he lies is a skeleton to remind us that the glory of this world passes away. In the handsome canopy above him, enriched with tracery and a delicate cornice, are ash leaves growing from tuns, and we see this play on his name again on the original iron grille still protecting his tomb. Other figures here are of Charles Townshend of 1817, and William Wilberforce sitting in a chair; this is the plaster model for his memorial in Westminster Abbey. The stalls and benchends with saints sitting on pinnacles under the fleur-de-lys poppyheads, and the beautiful piscina with interlacing arches are from the old church, and are over 700 years old. The fine screen at the west end is modern.

The lecture-rooms at the end of the college front are as old as the chapel, to which they are linked by fine railings. The Master's Lodge, on a site north of the library, is of the same time, and a little later is the range projecting from the north side of the two smaller courts.

Flickr.

* Having returned to Cambridge to do the 'new' chapels I asked the porters about chapel accessibility and it turns out only the antechapel is open to the public except during services - so misplaced irritation now shifted to wondering why it's closed to the public.