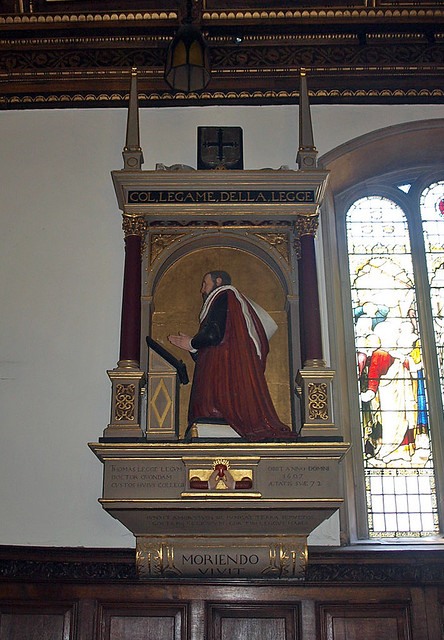

The CHAPEL, as has been said before, was built in the C14. It is of clunch, brick-faced. But of that nothing can be seen except for the remains of the Piscina W of Dr Legge’s monument. It marks the sanctuary, before the chapel was modernized and lengthened in 1637 (by John Westley). Later still, in 1716, it was ashlared (by John James of London). At that time also the big buttresses were built which were originally crowned by vases with stone-flames. The stair-turret between Master’s Lodge and Chapel (cf. similar surviving turrets at Peterhouse, Christ’s, and St John’s) was pulled down. It was re-erected in 1870, when the E apse was also added (by Waterhouse). The interior is prevalently of 1637. The ceiling dominates the effect. It is double-cambered and decorated with gilt suns just as had been done at Peterhouse a few years before. The organ gallery is made up of the original reredos of 1718. The apse was decorated in 1870 with Salviati mosaics. Stained glass by Heaton, Butler, & Bayne (Steel Memorial) and Burlison & Grjylls (Romanes and Paget Memorials, 1896 and 1900). - MONUMENTS several Brasses in the antechapel, one to a Knight, early C16, indent only; another to the Rev. Martin Davy d. 1839, with classical surround, designed by Will. Shoubridge of Caius College. - The most important monument is that to Dr Caius himself which stood originally on the ground. It was raised on its heavy brackets in 1637. It has two proud inscriptions, chosen no doubt by Caius who was always more interested in honour than in humility: Fui Caius and Vivit post funera Virtus. The monument was carved by Theodore Haveus of Cleves, whom Caius in the Annals calls a ‘skilful artifice: and eminent architect’. He was paid £33 16s. 5d. for it, and the alabaster and transport amounted to £ 10 10s. The monument is a six-poster (or rather five-poster as it stands against the wall). It is very elaborately decorated in the style of the Gate of Honour. There is no effigy. - Other Masters: Dr Legge d. 1607, large monument, the usual kneeling figure flanked by columns. - The same composition but more finely wrought: Dr Perse d. 1615 (Mrs Esdaile attributes this to Maximilian Colt, the sculptor of the Monument to Queen Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey). - Dr Gostlin d. 1704, a smaller very odd design, consciously original. No portrait, but a broken pediment on brackets bulging forward, and at the foot an equally bulgy frieze. - Sir James Burrough d. 1764, the Cambridge C18 amateur architect, black marble plate in the floor of the antechapel.

It has really three founders; Edmund Gonville, a Norfolk rector who died two years after its foundation in 1349; his executor William Bateman, Bishop of Norwich, who changed the site first chosen to the present one near his Trinity Hall; and John Caius, a Norwich physician who refounded the college he had entered in 1529. It was then that the 14th century Gonville Hall became known as Gonville and Caius College. Today it is usually called Caius and pronounced Keys. It was William Harvey’s college where he studied medicine before he discovered the fact of the circulation of the blood.

From Trinity Street we enter Tree Court, which occupies roughly the eastern half of the college site. The old buildings have been replaced by a fine modern range designed by Alfred Waterhouse, the walls enriched with gargoyles, oriel windows, and roundel portraits of some of the college’s famous sons. On the tower, facing the Senate House, are statues of Edmund Gonville holding a church, William Bateman as a bishop, and John Caius holding his Gate of Honour. A statue of Stephen Perse stands in the court: he was a tutor here before he founded his famous grammar school.

Dr Caius added to his architectural ability a leaning towards symbolism, and the new gateway from Trinity Street has taken the place of one of three he designed to represent the course of a student in the University. The first, now in the Master’s Garden, was the Gate of Humility; the second, at the entrance to Caius Court, still stands as he built it in 1567, with two figures, one having a palm branch and a wreath and the other a purse and corn of plenty. From Caius Court the student passes through the Gate of Honour to the Senate House over the way, where he receives his degree.

This gate is the most distinctive architectural ornament of the college, though much of the elaborate decoration of pinnacles, sundials, and gilded roses is gone. Over the plastered archway is a middle stage reminding us of the front of a Grecian temple, with architrave and niches between the pillars, and above this is a six-sided structure crowned with a dome.

For his court Dr Caius bought stone from the ruins of Ramsey Abbey church. The chapel and part of the Master’s Lodge are between it and the quietly dignified Gonville Court, which has much of its medieval walling. The 15th century hall and library have become houses and chambers; the new hall and the new library were built last century.

The chapel still stands where it stood in 1393, though it was lengthened and had the east end rebuilt in Charles Stuart’s day, was refaced in the 18th century, and was given its apse (projecting into Tree Court) in the 19th. Long and narrow, with panelled walls, it has a host of 70 cherubs in the panels of its richly gilded roof (1637). In the marble walls of the apse, below the five windows, are roundels of mosaic showing Eli and Samuel, Jesus in the Temple, Our Lord at Bethany, and other Bible figures; in the mosaic of the dome the sick are coming for healing. The striking thing here is the monument of Dr Caius, who sleeps in the chapel; now on the north wall, it has an ornate pillared canopy above a sarcophagus, coloured and gilded. Here are two kneeling figures of Thomas Legge and Stephen Perse, and there are brasses of an unknown knight of long ago and Martin Davy, Master at the time of Trafalgar and Waterloo.

Approached from Gonville Court, a two-winged staircase brings us to the hall, where the bearded portrait of Dr Caius presides over the high table. The hall is magnificent with rich screens, panelled walls, hammerbeam roof, portrait gallery, and heraldic windows; but one precious possession it has that must move all who come, for on the right of the portrait of Dr Caius a curtain shrouds a framed blue silken flag with the college arms. It was Dr Wilson’s flag, which he took with him to the South ‘Pole. There he was to have left it, but there they found the flag of Amundsen which hangs in another hall in Cambridge (the Scott Polar Institute), and Wilson brought his flag back with him and it was found in the tent where he lay with Scott's arm round him. Like a beacon it shines in his college hall, and a fancy takes us that in its presence these portraits on the walls incline their learned heads. One is Jeremy Taylor, and keeping him company are the father of Nelson, Shadwell the poet laureate, and Sir Thomas Gresham, founder of the Royal Exchange. In another room are Lord Chancellor Thurlow and Charles Doughty of Arabia. The fine buildings on the other side of Trinity Street, curving like a crescent round St Michael’s church, are of our own time.

From Trinity Street we enter Tree Court, which occupies roughly the eastern half of the college site. The old buildings have been replaced by a fine modern range designed by Alfred Waterhouse, the walls enriched with gargoyles, oriel windows, and roundel portraits of some of the college’s famous sons. On the tower, facing the Senate House, are statues of Edmund Gonville holding a church, William Bateman as a bishop, and John Caius holding his Gate of Honour. A statue of Stephen Perse stands in the court: he was a tutor here before he founded his famous grammar school.

Dr Caius added to his architectural ability a leaning towards symbolism, and the new gateway from Trinity Street has taken the place of one of three he designed to represent the course of a student in the University. The first, now in the Master’s Garden, was the Gate of Humility; the second, at the entrance to Caius Court, still stands as he built it in 1567, with two figures, one having a palm branch and a wreath and the other a purse and corn of plenty. From Caius Court the student passes through the Gate of Honour to the Senate House over the way, where he receives his degree.

This gate is the most distinctive architectural ornament of the college, though much of the elaborate decoration of pinnacles, sundials, and gilded roses is gone. Over the plastered archway is a middle stage reminding us of the front of a Grecian temple, with architrave and niches between the pillars, and above this is a six-sided structure crowned with a dome.

For his court Dr Caius bought stone from the ruins of Ramsey Abbey church. The chapel and part of the Master’s Lodge are between it and the quietly dignified Gonville Court, which has much of its medieval walling. The 15th century hall and library have become houses and chambers; the new hall and the new library were built last century.

The chapel still stands where it stood in 1393, though it was lengthened and had the east end rebuilt in Charles Stuart’s day, was refaced in the 18th century, and was given its apse (projecting into Tree Court) in the 19th. Long and narrow, with panelled walls, it has a host of 70 cherubs in the panels of its richly gilded roof (1637). In the marble walls of the apse, below the five windows, are roundels of mosaic showing Eli and Samuel, Jesus in the Temple, Our Lord at Bethany, and other Bible figures; in the mosaic of the dome the sick are coming for healing. The striking thing here is the monument of Dr Caius, who sleeps in the chapel; now on the north wall, it has an ornate pillared canopy above a sarcophagus, coloured and gilded. Here are two kneeling figures of Thomas Legge and Stephen Perse, and there are brasses of an unknown knight of long ago and Martin Davy, Master at the time of Trafalgar and Waterloo.

Approached from Gonville Court, a two-winged staircase brings us to the hall, where the bearded portrait of Dr Caius presides over the high table. The hall is magnificent with rich screens, panelled walls, hammerbeam roof, portrait gallery, and heraldic windows; but one precious possession it has that must move all who come, for on the right of the portrait of Dr Caius a curtain shrouds a framed blue silken flag with the college arms. It was Dr Wilson’s flag, which he took with him to the South ‘Pole. There he was to have left it, but there they found the flag of Amundsen which hangs in another hall in Cambridge (the Scott Polar Institute), and Wilson brought his flag back with him and it was found in the tent where he lay with Scott's arm round him. Like a beacon it shines in his college hall, and a fancy takes us that in its presence these portraits on the walls incline their learned heads. One is Jeremy Taylor, and keeping him company are the father of Nelson, Shadwell the poet laureate, and Sir Thomas Gresham, founder of the Royal Exchange. In another room are Lord Chancellor Thurlow and Charles Doughty of Arabia. The fine buildings on the other side of Trinity Street, curving like a crescent round St Michael’s church, are of our own time.

No comments:

Post a Comment