To the W and S are now C18 buildings, and to the E is Sir Christopher Wren’s CHAPEL. This with its adjoining colonnades was designed in 1666. The model arrived in 1667, and building was carried on from 1668 to 1674. The choice of Wren, not a famous architect yet, but the designer of Pembroke Chapel in 1663, was probably due to Dr Sancroft, Master from 1662-5 and then Dean of St Paul’s. He must have had dealings with Wren over the 1665 report on the restoration of St Paul’s (before the Cathedral was destroyed in the fire of 1666). Wren’s composition of a gabled chapel of three bays width and colonnades to the l. and r. with an upper storey over was taken almost exactly from Peterhouse chapel, built for Wren’s uncle in 1628-32. But where Dr Matthew Wren’s architect still used a mixed Gothic and Jacobean vocabulary, Christopher Wren worked with Italian motifs exclusively, although using them in an oddly unclassical way. Pembroke Chapel is much purer in the new classical style than the later Emmanuel Chapel. First of all, as far as planning goes, the chapel front is strictly speaking a sham. The chapel itself lies back behind the front which holds on the ground floor an open porch and on the upper floor part of the Master's Gallery, a Picture Gallery which extends all along the two colonnaded wings and the chapel front. Then, as far as elevational details go, the colonnades have closely-set round-headed arches on square piers, the centre, however, has two round-headed arches and one depressed segmental arch.* The chapel front has two giant angle pilasters, but the central bay has demi-columns so that the frieze above - decorated with garlands - slightly projects in the middle. The front is finished by a pediment, but since on the projecting centre part of the frieze stands a square block with the clock, the sides of the pediment seem to disappear - a decidedly Baroque feature. On the block with the clock rests a big, rather heavy lantern, less elegant than that over the street end of Pembroke Chapel. The long sides of the chapel are of plain ashlar work with arched windows set into rectangular frames. The INTERIOR has a splendid plaster ceiling by John Grove who also worked for Wren at Pembroke College. The woodwork of 1676 was designed by Pearce and Oliver of London and executed by Cornelius Austin (1678). ** The COMMUNION RAILS are especially beautiful. The ORGAN CASE is of 1686 (by Father Schmidt), the REREDOS of 1687. The PAINTING in it, the ‘Return of the Prodigal Son’, is by Jacopo Amigoni and was presented in 1734. Amigoni came to England in 1729 and lived here for several years. The CHANDELIER in the chapel was given in 1732. The STAINED GLASS, put in a propos Sir Arthur Blomfield’s general restoration of 1883 is by Heaton, Butler, & Bayne.

* But this anomaly does not exist in Wren’s drawing.

** For woodwork by Pearce cf. also Sudbury, Derbyshire.

Every good American accepts the invitation of the gateway in its classical front to enter the older quadrangle, for through it John Harvard passed as an Emmanuel man. At the tercentenary of the college in 1884 Harvard men placed a memorial window to him in the chapel. But the expectation that his room can be found is an illusion. Nobody knows exactly where he lodged; yet certainly he sat in the chapel, dined in the hall, and let his eyes rest on the ancient wall of the monastery of the preaching friars which was here when Queen Elizabeth’s Chancellor, Sir Walter Mildmay, took over their 13th century monastic buildings and established in their stead this college. The story is told that when Mildmay came to Court Queen Elizabeth charged him with setting up a Puritan foundation, and Sir Walter answered: “No, madam; but I have set an acorn which, when it becomes an oak, God alone knows what will be the fruit thereof.”

The old wall is one of the few reminders of this origin, and the delightful garden of which it is the boundary has the old fishpond, now a lake where swans and cygnets float among the lilies. The noble gardens are the most abiding impression of Mildmay’s foundation, which has been considerably extended by other benefactors.

The buildings are a mingling of styles, perhaps the most persuasive being the cloistered block designed by Wren. Its striking west front, facing the entrance, embraces the gallery of the Master’s Lodge above the cloister, and the west end of the chapel roof, which has a clock tower with a cupola breaking into a pediment. The chapel itself pushes into a garden, which has a mulberry tree, a tremendous beech, and a swimming bath for the Fellows, whose garden this is.

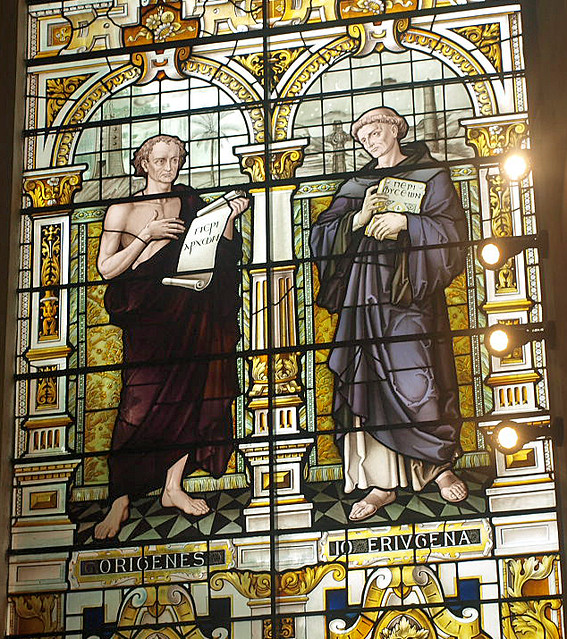

The chapel has a floor of black and white marble, and Cornelius Austin’s woodwork in the fluted and gilded background of the altar and the rich wall-panelling. In the magnificent plaster ceiling is a lovely oval wreath of flowers, and from it hangs a splendid candelabra in 18th century glass. In the fine gallery of portraits filling the windows we see John Harvard (with a ship in the background), Laurence Chaderton, who was chosen by the founder to be first Master of the college, Thomas Cranmer with his Book of Common Prayer, John Fisher, Anselm, and Augustine; with churches or colleges for their background are John Colet, Tyndale with his New Testament, Benjamin Whichcote, Peter Sterry, John Smith, and William Law.

The hall on the north side of the first court has a richly moulded ceiling, and a classical screen with fine doors of ironwork. The panelled wall behind the high table has gilded pilasters, and here hangs the portrait of the founder in a fur-lined gown, with ruffs at the neck and wrists, and rings on his fingers. Other portraits here are of Sir William Calvert 1761, John Balderston 1719, James Gardiner 1705, Peter Giles 1935, F. J. Anthony Hort 1892, William Richardson 1775, Anthony Askew 1774, and Thomas Young 1829. A second hall near by was originally the founder's chapel, and the lower part of its walling belongs to the monastic buildings Mildmay found here. Some of the modern panelling opens to show the old masonry. We enter through a massive oak screen which was hidden for centuries behind plaster and brickwork. Here are painted portraits of John Bickton of 1675, Sir Walter Mildmay of 1589, Thomas Holbeach of 1680, and Archbishop Sancroft in his robes, sitting at a gilded table on which is a paper with the words, To the King. Sir Anthony Mildmay of 1617 and Charles Fane of 1691 are also here. This old chapel served for a time as the library; now a modern library stands by the Close, with a low brick building of the 17th century for company.

The old wall is one of the few reminders of this origin, and the delightful garden of which it is the boundary has the old fishpond, now a lake where swans and cygnets float among the lilies. The noble gardens are the most abiding impression of Mildmay’s foundation, which has been considerably extended by other benefactors.

The buildings are a mingling of styles, perhaps the most persuasive being the cloistered block designed by Wren. Its striking west front, facing the entrance, embraces the gallery of the Master’s Lodge above the cloister, and the west end of the chapel roof, which has a clock tower with a cupola breaking into a pediment. The chapel itself pushes into a garden, which has a mulberry tree, a tremendous beech, and a swimming bath for the Fellows, whose garden this is.

The chapel has a floor of black and white marble, and Cornelius Austin’s woodwork in the fluted and gilded background of the altar and the rich wall-panelling. In the magnificent plaster ceiling is a lovely oval wreath of flowers, and from it hangs a splendid candelabra in 18th century glass. In the fine gallery of portraits filling the windows we see John Harvard (with a ship in the background), Laurence Chaderton, who was chosen by the founder to be first Master of the college, Thomas Cranmer with his Book of Common Prayer, John Fisher, Anselm, and Augustine; with churches or colleges for their background are John Colet, Tyndale with his New Testament, Benjamin Whichcote, Peter Sterry, John Smith, and William Law.

The hall on the north side of the first court has a richly moulded ceiling, and a classical screen with fine doors of ironwork. The panelled wall behind the high table has gilded pilasters, and here hangs the portrait of the founder in a fur-lined gown, with ruffs at the neck and wrists, and rings on his fingers. Other portraits here are of Sir William Calvert 1761, John Balderston 1719, James Gardiner 1705, Peter Giles 1935, F. J. Anthony Hort 1892, William Richardson 1775, Anthony Askew 1774, and Thomas Young 1829. A second hall near by was originally the founder's chapel, and the lower part of its walling belongs to the monastic buildings Mildmay found here. Some of the modern panelling opens to show the old masonry. We enter through a massive oak screen which was hidden for centuries behind plaster and brickwork. Here are painted portraits of John Bickton of 1675, Sir Walter Mildmay of 1589, Thomas Holbeach of 1680, and Archbishop Sancroft in his robes, sitting at a gilded table on which is a paper with the words, To the King. Sir Anthony Mildmay of 1617 and Charles Fane of 1691 are also here. This old chapel served for a time as the library; now a modern library stands by the Close, with a low brick building of the 17th century for company.

No comments:

Post a Comment