Pevsner's entry can be read here.

PETERBOROUGH. Here on the edge of Fenland, a little way from Ermine Street, stands one of the grandest Norman monuments in Europe. It has grown out of the 7th century Abbey of Medeshamstede, the meadow homestead, founded in 655 in the reign of the Christian King Peada, son of the pagan King Penda who did what he could to stamp out Christianity in the Island. Under Abbot Saxulf, befriended by King Peada, the abbey in the meadow became one of the most important religious centres in a country where Christianity was still fighting for its life. A settlement grew up round it, and when five centuries had come and gone.a traveller coming this way would have found the Normans busy with their hammers and chisels transforming the Saxon abbey into a minster that has outlasted their dynasty and will, we may be sure, outlast whatever dynasties there may be for another thousand years. They made it into the marvellous place we see today, fit to rank with any building that stands in Europe.

There it stood as the centuries went by, majestic, solemn, wonderful, yet almost solitary through the long generations of medieval England, for (except that Henry the Eighth thought so much of it that he made it a cathedral with a diocese) nothing happened round about this small cathedral city until the railway came and Peterborough began its rise from a country place with a few thousand people to the status of an industrial centre of the Midlands and a population approaching 50,000. We may imagine that but for the railway Peterborough would be today a place like Southwell, a cathedral of great splendour with a village gathered about its walls.

Yet it has known exciting days. The first Saxon settlement was burned out by the Danes, coming like Nazis with fire and sword across Mercia. Abbey after abbey they left in ruin, Crowland, Thorney, Ramsey, Ely, and Medeshamstede. The good Archbishop Dunstan encouraged the Abbot to build again, and a new Saxon church arose and was dedicated in 972. A wall was built round the settlement and a keep within it, and this little new town gave itself a new name; it called its church St Peter’s and the town St Peter’s Burgh. Abbot Leofric became so powerful that he ruled five abbeys at once, and the minster grew so rich in his time (the time of Edward the Confessor) that the little town was known as the Golden Borough. The brave Abbot marched with King Harold and meant to fight at Hastings, but he fell sick and was brought home again, and here he died on the third day after the battle that ended Saxon England and made the Conqueror king.

It was in these troubled days that Hereward the Wake, the last Saxon squire to resist the Conqueror, gathered little hosts of Danes and attacked the abbey, carrying off its treasure, burning the houses, but sparing the church. He was that Hereward whom Charles Kingsley made into a hero for every English lad, and he declared that he only wished to save the treasure of the abbey from the Normans. However that may be, the church that Hereward had spared was burned down in the generation after him, and in 1117 John of Sais began the building that we see, ranking with those imperishable glories of Norwich and Durham and Tewkesbury. It remained an abbey for nearly nine centuries from the days of Abbot Saxulf, and then came Henry the Eighth and took it over from John Chambers, the abbot who was a man of peace and “loved to sleep in a whole skin and desired to die in his nest.” Some abbots the imperious tyrant broke to pieces, but Abbot Chambers he rewarded for his docility, making him first Bishop of Peterborough.

We come to four gateways as we walk towards the cathedral, the great west gateway of the Minster precincts, the medieval gateway into the Bishop’s garden, the Tudor gateway to the Deanery, and the Norman gateway into the Cloister Court. The great west gateway, with the 14th century chancel of St Thomas of Canterbury beside it, is the finest of all the monastic buildings now standing. It is Norman and was built by Abbot Benedict, but has a 14th century front with a moulded arch. On each side of the lovely entrance arch is a Norman arcade with a doorway in it. One doorway leads into what remains of the King’s Lodging in ancient days, another brings us to an upper room once a chapel and now a classroom. The vaulted Norman chamber on the ground floor was used by the abbots as a prison and remained the town gaol until the middle of last century, having still the old door with a formidable bolt which opened into the condemned cell.

Abbot Godfrey’s medieval gateway into the gardens stands out from a row of modern buildings on our right as we approach. It is 32 feet deep with arcading on its inner walls, and a vaulted roof supporting the Knight’s Chamber. On both faces of the gateway are three figures in niches, those on the north being Edward the Second between an Abbot and a Prior, those on the south Apostles. The gateway into the deanery grounds on the left of the green in front of the cathedral is richly carved with Tudor devices, having been set up in 1510; the church on a tun over its smaller arch is a play on the name of Abbot Kirkton.

The Norman gateway into the cloisters (called Laurel Court) is reached by a narrow passage to the right of the cathedral. The cloisters were a great square with 168 yards of walks, and had windows with painted glass, but they are now a ruin. The west wall has a Norman arch remaining in its solid masonry. The south wall has two elegant pointed doorways, one having a round arch richly carved with a band of frogs and queer devices, and a tympanum with reptiles carved on each side of a quatrefoil. The effect of the small arch within the deep mouldings of the medieval arch is delightful, and this doorway is known as Heaven’s Gate.

Here are two doorways leading from the cloister into the cathedral, the Canon’s and the Bishop’s. The Canon’s doorway is Norman, the Bishop’s 13th century. The Norman doorway, impressive with a flight of steps and four columns at each side, has outer arches carved with fleur-de-lys and zigzag with two plain arches between. The medieval doorway has three elegant columns supporting its 13th century arches.

The Refectory stood behind the south wall of the cloister court, and in the bishop’s garden are some of its carved remains. There are many arches and fragments of old monastic buildings, the most striking being the tall graceful arches of the Infirmary, with an arcade of the l3th.century standing free in space. In the middle of the Cloister is a Norman well to which the white-robed monks would come for water. It was lost for centuries and has been discovered in our time. The mouth of the well was closed by a huge gravestone, but a depression in the turf led workmen to excavate, whereupon they found three steps leading to the water, and square walling showing fine Norman tooling.

It is a noble view of the walls of the cathedral that the cloisters give us, with graceful Norman arches by the hundred, stately windows of all our building centuries, and the solid and dignified central tower crowning it all. Here we see every age of this great cathedral except the Saxon; and it is an impressive spectacle, for these walls are crowded with the masterly strength and grace of the round arches of the 12th century, the delightful decorated parapet of the 13th, and stately windows with the simplicity of the 13th, the decorative development of the 14th, and the rich tracery of the 15th.

Few cathedrals have more delightful exteriors, and Peterborough is remarkable for three things the traveller sees before he comes inside, three additions to this Norman fane (at the middle and the ends) that do not spoil it, but enhance its glory. One is the central tower which, still on its Norman foundations, was raised to its battlements in the 14th century and last century was taken down and rebuilt stone by stone. Another is the lovely 15th century building enclosing the apse and is still called the New Building. It gives a delightful aspect to the east end of this great place, lengthening the cathedral by many feet, its fine walls pierced with 13 windows and crowned with a richly decorated parapet. Twelve massive buttresses hold up these walls, crowned by seated figures believed to represent the Apostles, and all much worn by the winds and rains of 500 years. The third great addition since Norman days is the incomparable west front, for the Normans had no great front to their building but left it for the 13th century to add. The main stages of the cathedral therefore cover four centuries, the main structure 12th century, the west front 13th, the central tower 14th, the east end walls 15th.

It is the marvellous west front which remains forever in the memory of all who behold it. Looking at this front across the grassy space the traveller’s mind runs back to Salisbury and Wells. It has the same sense of something rare and wonderful, something majestic, and with a strength that has kept it where it is for 700 years, yet with a soaring lightness that holds us spellbound by its enchantment. William Morris thought of it all when he wrote his Earthly Paradise:

I who have seen

So many lands, and midst such marvels been,

Can see above the green and unburnt fen

The little houses of an English town,

Cross-timbered, thatched with fen-reeds coarse and brown,

And high o’er these, three gables great and fair,

That slender rods of columns do upbear

Over the minster doors, and imagery

Of kings and flowers no summer field doth see,

Wrought in these gables.

It is a true image that the poet gives us of this west front, with its appealing beauty, its variety within a scheme of ordered symmetry. The whole mass is superb, with no suggestion of weight about it. There must be well over a mile of slender columns in these three noble arches soaring 81 feet high, and outside and above them rise lovely towers and gables and turrets adorned with delicate arches, wheel-windows, pierced arcading, carved pinnacles. and impressive statues. We wonder that so delicate a thing can have survived the buffetings of our English weather for six or seven hundred years and show so little sign of weariness or age. Professor Freeman called it “the noblest conception of the old Greek translated into the speech of Christendom,” and truly it is one of the grandest fronts in Europe. It completes with Gothic splendour the mighty work of the Normans behind it.

The great minster is 158 yards long, and of this 130 yards was built by the Normans in the space of 80 years. They left the west end unfinished, and in the next generation the English builders crowned it with these great towers and arches, so linking the work of the Conqueror’s men with that of the English builders who were to crown this island with such wonder for the next 300 years. The three stupendous arches of the front are crowned with delightful gables, the wide sweep being extended and completed by a slender tower on each side. The columns of the arches are unattached to the west wall of the cathedral, which the English builders covered with doorways, windows, and arcading, giving the arches a rich background. Over a century later (about 1370) the builders set a porch in the central arch rising halfway to the top. It may have been desirable as a support to the great piers, but the work was done with no suggestion of an afterthought, for this fine and delicate structure in no way spoils the dazzling spectacle.

The porch has delightful towers on each side, rising in two storeys enriched with niches and arcading, and above the arched doorway is a great traceried window crowned with an embattled roof. The porch runs back to join the arch of the main doorway into the minster, and has side arches opening into the space between the west front and the inner west wall. The vaulted roof has carved bosses, one of which is thought to be unique; it is a Trinity, and shows the Father with a beardless face holding the Risen Christ, with the Holy Spirit appearing in the form of a dove and seeming to be speaking to the Father.

Soaring up the towers and running across the gables of this front, and set in the spandrels of the great arches, are scores of smaller arches, some with windows, some with ornament, some with statues of benefactors and apostles. The base of each gable is filled with a rich arcade framing four windows and three apostles, with another apostle in the top of each of the three gables, completing the Twelve. St Peter presides in the centre. In the middle of each gable is a beautiful wheel-window, the central one with eight spokes, the others with six. Each of these round windows is set between two niches with statues of kings in them, so that each gable has four apostles and two kings. The niches in the spandrels of the great arches have twelve statues of benefactors of the minster, so that there are 30 figures in all. They are all very vivid, though some are badly battered by the wind and rain. The expression on the face of St Peter is remarkably good; he is giving his blessing with his right hand and has two keys in his left.

All three gables are crowned with a finely decorated cross, and between the gables are delightful octagonal turrets through which we see the sky. There are similar turrets on the bell-tower rising behind the front. The two towers belonging to the west front are crowned with pinnacles and soaring spires. It is the turrets and pinnacles of these western towers which add much to the feeling of lightness and delicacy of this great structure.

The central doorway which brings us in is divided by a noble pillar rising from a richly carved base on which a monk is being tortured by demons, a sculpture put here 700 years ago, apparently to encourage moral discipline in all who come into this fine place. The west wall pierced for this doorway has five 13th century windows filled with 15th century stone tracery, and arcading covers the wall running beyond the clustered piers of the arches and round the graceful sides of the towers. The arched door by which we enter has opened and shut for 700 years to admit every traveller who has come this way; it is carved with foliage on the capital of its central post, and its cross-pieces still have the ornament put there by the 13th century carpenter. We open this ancient door and are thrilled to find ourselves in Norman England. All about us is a spectacle unsurpassed, and only equalled in our island by the Norman splendour of Norwich, Durham, and Tewkesbury.

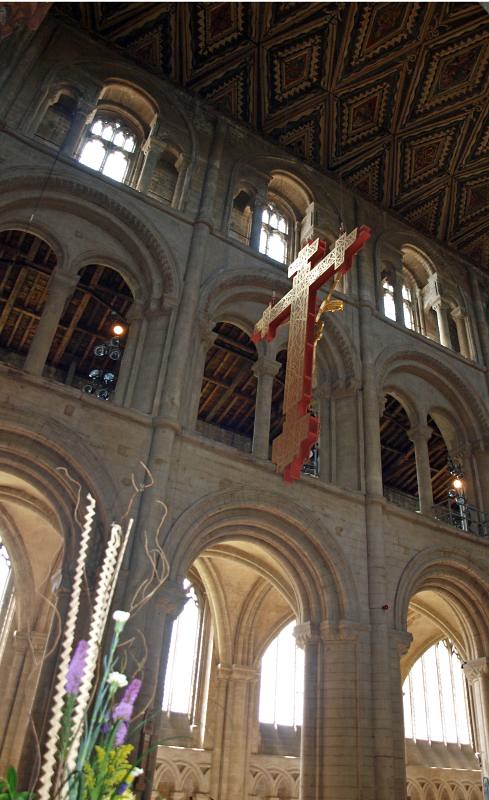

It is the simplicity of this vast place that strikes us first. The severe beauty of it all rises up to the triforium and the clerestory, the mighty columns bearing tier on tier of round arches of various sizes and groupings (single arch, double arch, triple arch as they rise), admirably proportioned and graduated so that we have the same feeling of lightness and grace that comes to us at the West Front. It is Norman at its purest and best, strength without a sense of over-bearing weight.

We notice that the English builders of the towers rising above the western transept could not but pay tribute to this Norman splendour by building in keeping with its style; they even used the Norman arches in the upper windows on each side, and used round arches for the frames of three doorways. We are standing where Norman hammers and axes were resounding eight centuries ago, and well may we wonder at it all, for this vast nave, begun in 1117, was finished before the century was out and is truly as magnificent as anything made by hands can be. The massive piers have clustered columns about them and arches of three orders, almost plain, with simple capitals; the great arches of the triforium are carved and have a pair of smaller arches set in each; and stately half-columns rise between the arches to the top of the lofty three-arched clerestory, touching the famous painted roof which crowns the longest, widest, and loftiest Norman nave in England.

Fitting it is that such a nave should have such a roof, for it is unique in England, the only Norman roof in any of our cathedrals; the wood is Norman and the painting English. There are only a very few surviving Norman timbers in our churches, and only one or two roofs among them, but nowhere is anything so spectacular as this. It is 204 feet long and 35 feet wide, and is divided into diamonds. In each diamond is a painted figure which has been there since about 1220, though the roof was repainted in 1834. The figures are sacred and grotesque, and worthy of another restoration. Here, among kings, queens, and minstrels, is Peter with the keys, and among the grotesque scenes are a monkey carrying an owl and riding backwards on a goat, a mother entertaining her child with a red cup and ball, a man with the head and feet of a donkey, and a lion dancing to an ass playing a harp. It is believed that the roof was made flat by the Normans but has since been raised and given sloping sides.

It was at the time of the raising of the ceiling that the Lantern Tower was restored in the 14th century, its east and west arches being made higher and pointed — the only alteration of the Norman work. The Norman arches of the transepts were not touched, however, and these superb structures, each with four bays, are as the Normans saw them, with simple arcading round the walls below the windows. Each transept has chapels, three in the south and one in the north. The southern chapels are dedicated to St Oswald, St Benedict, and St Kyneburga with St Kyneswith (the two Castor saints); in the Oswald Chapel is a stone stairway leading to an upper chamber. The northern chapel is dedicated to St Ostry. The beautiful wooden screens enclosing all the transept chapels are 15th century. In the west wall of the south transept is a richly carved 14th century doorway into a Norman chamber, with a stone vaulted roof, which is now the Sacristy, and in the north wall of the north transept is a rare Norman doorway, with a tympanum of scale-work, leading to the triforium.

But we have come into the transepts forgetting a glorious spectacle on the way, for it happens at Peterborough that the oak choir-stalls are in the two bays of the nave before the crossing. Modern, they are in striking contrast to their massive and severe environment. The stalls are richly traceried and canopied, the canopies being octagonal and in three stages, and each canopy crowned with a niche for a carved figure. There are 44 of these figures, all given by friends or by the Freemasons of England, and most of the statues are of people associated with the minster.

These are the names of the figures, beginning at the dean’s stall and going east on the south side. The dean’s stall has St Paul and St Andrew above it, and going east are: The patron saint, Peter; the first Saxon abbot, Saxulf; abbots from 971 to 1496, in this order: Adulf, Kenulf, Leofric, Turold (appointed by the Conqueror), Ernulf, Martin de Bec, Benedict (builders of the nave) Martin of Ramsey, John of Calais (builder of the cloisters), Richard of London (builder of the north-west tower), Adam of Boothby, William Genge, Richard Ashton (who began the New Building), and Robert Kirton (who finished the New Building). Next come three bishops (Towers, White, Magee) and three deans (Patrick, Saunders, Perowne).

On the north side of the stalls are these: King Wolfere and King Ethelred on the Vice-Dean’s stall, and then: King Peada, founder of the monastery; Abbot Cuthbald, Saxon; King Edgar of Mercia and his queen; Abbot Brando, 1066; Hereward his nephew, the great patriot; John de Sais, who started the choir; Abbot Hedda, slain by the Danes; Robert of Lindsey, with a model of the west front which he saw built; Godfrey of Crowland, with a model of the palace gateway; William Ramsey, abbot; Prior William Parys, builder of the Lady Chapel, now gone; St Giles, with the hind that took refuge in his cell; Hugh Candidus, chronicler and prior of the monastery; Abbot Overton; Catherine of Aragon; Dean Cosin; Prebendary Gunton; Bishop Marsh; Bishop Davys; Dean Monk; Dean Argles.

There are smaller figures tucked away in the carving of the canopies, from the Old and New Testaments; and on the two western stalls are carved panels of much interest. Four on the south represent the miracle by which the arm of St Oswald was preserved, this having been one of the relics of the monastery; on the north are four panels telling the story of Ethelwold, the great church builder of Peterborough and Winchester.

We have now completed the nave and may cross into the choir proper, looking up on our way into the vaulted roof of the Lantern Tower, with its painted medieval carving. The central boss shows Our Lord holding an orb, and other bosses have the symbols of the Evangelists. The transept roofs on each side are original, but are not painted. The roof of the choir is of wood to match the nave roof, but is 15th century and flat, carved and painted with bosses of the Crucifixion, the Devil with a wooden leg, three fishes, three lilies, and angels on medallions. The ceiling of the apse is painted to show Christ as the true vine and the disciples as the branches.

The coloured roof of the choir looks down on a tessellated pavement of a thousand rainbow hues, the patterns varying as we go east to the baldachino, which rises 35 feet and stands on a dais; it is of alabaster from Derbyshire and is a memorial to Dean Saunders, given by his children. From the four marble columns at the corners of the baldachino spring decorated arches with mosaic spandrels, and in canopied niches stand the Four Evangelists. The central panel at the front is a figure of Our Lord, and at the back in the same position is St Peter. The mosaic floor of the choir, with the wooden throne and the pulpit, were given by Dean Argles, who was here for 43 years; and in memory of him are the iron screens enclosing the choir, fine pieces of craftsmanship.

The throne is raised on three steps with a lofty canopy and a spire. On the sides are Peter and Paul, and on the book-rest are symbols of four Virtues - Temperance, Wisdom, Fortitude, and Justice. On the lower tier of the canopy are six figures of abbots and bishops: Saxulf, the first Abbot, Cuthbald, John de Sais, Benedict, Hugh of Lincoln with his swan, and John Chambers, last abbot and first bishop. In the upper tier are four bishops: Dove, Cumberland, Kennett, and Magee. The oak pulpit is also very elaborate. Round the base are arcading and four niches with abbots: John de Sais with the model of the apse, Martin de Bec, William of Waterville, and Walter of St Edmunds. Round the pulpit itself are three preaching scenes, with four saints in canopied niches dividing them: Peter, Paul, James, and John. The three scenes are attractively grouped, showing Abbot Saxulf converting the Mercians, Christ sending out the Apostles, and Peter preaching after Pentecost.

The choir has four bays, and it is interesting that all the tympana of the recessed arches under the main arcade of the triforium have different varieties of ornament. In two of these we see round holes pierced through the stone, the far-off beginning of tracery. The great bronze lectern (which must long outlast the wooden lectern in the nave) has a medieval bronze eagle on its original base, given to the minster by two men of the monastery, Abbot Ramsey and Prior Malden, of the 15th century. It may have been from this lectern that an angry Cromwellian soldier seized the big velvet-covered Bible now seen in the glass case in the nave. The story is that he took also a prayer book, some silver, and the altar candlesticks, and that when he showed them in triumph to his colonel the officer sent him back with his loot. In the choir aisles are two interesting fragments of ancient timber, one Norman — a pair of thin wooden pillars from the time when the English style was displacing the Norman, for below the Norman carving are gilded 13th century capitals cut with foliage. These are in the Ostry Chapel entered from the north aisle; in the south aisle hang three miserere seats with carving probably belonging to the original choir-stalls.

From either of these choir aisles we come into the 15th century’s great contribution to the cathedral, the New Building enclosing what is probably the finest Norman apse in the kingdom, with five bays divided by clustered shafts rising to the roof. The tracery in the upper windows is 14th century, and the three eastern arches were opened to the ground when the apse was enclosed by the splendour of the new East end, in the golden age of English architecture.

The New Building is in the style of the famous King’s College Chapel at Cambridge, and the eye is instantly drawn to the marvellous fan tracery of its roof, a wondrous spectacle. The roof is supported on two fine piers, richly carved arches, and the twelve outside buttresses crowned with the Apostles. It is the supreme wonder of this perfect little building, so filled with light from its great windows. The stone fans are like fine lace, and worked in among them are huge bosses of the lions of England and crowns pierced with arrows. The walls are arcaded below the windows, the arches being finely carved, and on the great entrance arch from the south choir aisle are many small devices, among which we read the last exultant verse of the Psalms, “Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord.” Everywhere it is evident that the 15th century craftsmen building this lovely place felt that nothing but the noblest work of man would do.

Here, in the newest part of the cathedral, the oldest treasure lies. It is a great sculptured stone believed to be Saxon, with six full-length figures on each side and primitive ornament on its roof-like top. It is said that it is the shrine made to commemorate the massacre by the Danes of Abbot Hedda and his monks in 870, but this has been questioned, and it is possible that it may be earlier work still, part of the shrine of St Kyneburga brought here with her remains in the 11th century. The sculpture is distinctly like that of a Saxon figure preserved in Castor church. All these twelve figures are crowned with a halo, and the halo round the head of Our Lord is marked with a cross. The shrine has been out in the winds and rains for centuries and is much worn, but it is a little masterpiece.

But if we would go back to the far-off Saxon beginnings of this place we come down the steps near the south-west pier of the lantern tower. The foundations of the transepts and the choir were found when this pier was rebuilt in 1883, and down these steps we may descend to view them. We may kneel in the very place where Hereward the Wake was made a knight, and where he would kneel through his vigil. It is the most thrilling spot in Peterborough. Here are fine stones believed to be part of the first Saxon church, and coffin lids with handsome crosses by Saxon masons. Fragments of carving from the church are worked into the pier, and other pieces of charred stone and timber from here are preserved behind glass in an aumbry of the south choir aisle, opposite the lovely 13th century piscina.

As we enter this south choir aisle we come upon the magnificent Norman arch for a tomb in which three abbots were laid, and here still lies the figure of one of them, said to be Abbot Andrew, laid to rest about 1200. It is one of six tombs of abbots which all travellers come to see, four more in this aisle, and a sixth in the aisle on the north of the choir. It has not been possible to identify two of the abbots, but Alexander of Holderness is known by a metal plate found on his coffin; we can see the plate with fragments of the abbot’s boots and clothing in a case in the nave. Alexander died in 1226 and has a very elaborate canopy. John Chambers, the last abbot and the first bishop, had his image carved in stone during his lifetime, and here it remains, much worn. Abbot Benedict, who lies in the north choir aisle, not far from a magnificent 14th century chest, is a very stately figure with his crozier ending in the mouth of a superbly carved reptile at his feet. All the six abbots hold croziers in their right hands and books in their left, and they are probably the best group of Benedictine monks in England, splendid figures in stone and marble.

This cathedral, which is not rich in monuments, has had within its keeping the bodies of two queens, tragic figures both, Catherine of Aragon and Mary Queen of Scots. No wall-monuments mark their resting-place, only two flags for each poor queen. The Queen of Scots has gone, and has a magnificent tomb in the richest chapel in the land, a few feet away from the tomb of Queen Elizabeth who signed her death warrant. Queen Catherine lies under a marble stone put here by the Catherines of England, Ireland, Scotland, and America in 1895. But the flags of England and Aragon are all the glory that is here to mark the grave of one of the most pathetic women in the world, first wife of the imperious Henry the Eighth, first victim of his wrath, though happily our royal butcher spared her life. As we stand by the grave of this much-wronged lady, stranger in a strange land, we may remember the words which Shakespeare makes her say as she lay dying:

When I am dead

Let me be used with honour; strew me o’er

With maiden flowers, that all the world may know

I was a chaste wife to my grave; embalm me,

Then lay me forth; although unqueened, yet still

A queen, and daughter to a queen, inter me.

Mary Queen of Scots was buried here by night, and an old pamphlet tells us that the body was brought from Fotheringhay in a coach with about a hundred men attending. Queen Elizabeth paid £321 l4s 6d for the funeral, which was followed by a formal procession through the city the next day. The coffin borne through the streets in the procession was empty though the fact was not known to the people; it was empty because the actual coffin with the body was so heavy that it could not have been carried. It weighed nearly half a ton. It was let into the grave by candlelight, and four officers attending broke their white staffs and threw them into the grave. Two Scottish flags hang on the piers to mark the place from which King James removed his mother’s body to Westminster Abbey in 1612.

Perhaps the most famous of all the varied memorials is the curious picture of Old Scarlett which hangs on the west wall of the nave. He was the verger who buried the two queens, and it was his boast that he had buried the whole population of the city twice over. He lived from 1496 to 1594 and his whole life was bound up with the cathedral.His picture, which is not the original but a copy made in 1747, shows him holding a spade, a pickaxe, keys, and a whip, and at his feet is a skull, grim symbol of his office. Under the portrait are 12 lines of rhyme. In the parish registers of St John’s Church it is recorded that there was paid to Old Scarlett “being a poor old man, and rising often in the night to toll the bells for sick persons, the weather being grievous, and in consideration of his good service, towards a gown to keep him warm, 8s.”

The minster would be much richer in shrines and tombs but for the destruction of the Civil War; but one richly carved 15th century shrine remains by the wall of the apse, just inside the New Building. It is believed to be the tomb of a kinswoman of St Kyneburga and St Kyneswith, the Christian daughters of the pagan King Penda. She is known as St Tibba, and is supposed to have been the patron saint of hunters, having a frieze of carved animals and birds on her shrine. It is thought that the shrine was once the reredos of one of the cathedral’s 22 altars, and it is said that the stone now resting on the altar of St Oswald’s Chapel is from another of these altars. Also in the New Building is a ruined fragment of the 17th century monument to Sir Humfrey Orme who had it erected in his lifetime and saw it in ruin. Near it Thomas Deacon, who founded a school at Peterborough which still bears his name, reclines lifesize on his 18th century tomb. There is a wall-monument to Bishop Cumberland who died in 1718, and a tablet of 1695 to Roger Pemberton, whose epitaph has a line of Greek from Homer: “The race of men is as the race of leaves.” Modern figures on tombs in the New Building are of Dean Ingram with a long beard, Bishop Clayton of Leicester in the more severe style of modern art, and there is a portrait head of Frederick Cecil Alderson who died in our own century after being chaplain to two monarchs; he wears a mortar board and his medallion is encircled by a bronze wreath.

In the south choir aisle is the white marble memorial of Archbishop Magee with a lifesize portrait of Bishop Mandell Creighton near it. Bishop Creighton lies in St Paul’s, having been Bishop of London, but he was six years bishop here; his epitaph is a little unfortunate in saying that he tried to write true history. Archbishop Magee lies in the burial ground here, and his epitaph describes him as one of the outstanding figures of last century. Unfortunately he is too often remembered by one of the stupidest sayings of the century — that he would rather see England free than sober. Edith Cavell and her teacher are both remembered in the nave by bronze tablets on piers. Nurse Cavel1’s portrait is in relief with a tablet saying that she was a pupil at Laurel Court School, and her teacher’s tablet tells us that Margaret Gibson was the blind Principal of the School for 40 years and the first woman to receive the freedom of the city. On the west wall of the nave is a bronze relief of a soldier known as the Lonely Anzac; he was Thomas Hunter, and died in Peterborough during the First World War, this memorial being shared with Peterborough by the citizens of his home town in New South Wales. Close by, on the south arm of the western transept, are the names of the men of St Peter’s Training College and the Old Boys from the King’s School who fell in the First World War, and on the opposite wall, in the Baptistry, is a tribute to King Peada who founded the first monastery. The font basin is 700 years old and was rescued from a garden.

The only old glass at Peterborough is a collection of fragments from the l4th and 15th centuries in the central windows of the apse; in it we can recognise St Peter receiving the keys from the Master. The windows have no special merit, but one in the south transept is by Rossetti, a vivid piece of colour showing the lowering of Joseph into the pit by his jealous brothers. The brother letting Joseph down is remarkable for having a head like the artist’s wife, with her mass of red hair. A window in the Oswald Chapel has Our Lord on the Cross between St Leonard and St Crispin; and in the New Building are five stained windows in memory of Dean Barlow (with groups of Jews and Gentiles below the figures of Peter and Paul, and angels with a scroll saying, “Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel”); Dean Butler; Dean Davys; Canon Twells, who wrote At Even, ere the sun was set; and Canon Alderson, with models of the cathedral and two churches he ministered in. The west window is in memory of men who fell in the South African War, and has two rows of five lights, with Paul, Peter, and Andrew, King Peada, and Bishop Ethelwold in the top row, and St George, St Michael, St Alban, Josiah, and Gideon below.

The cathedral library is in the room over the great west porch and in it is one of the rarest treasures from the 13th century, the Swapham Cartulary; in it is the receipt for ten shillings paid for its return by a soldier in the Civil War. The library has also a 14th century Bible with a delightful illumination of angels on Jacob’s Ladder.

The city has little history apart from the cathedral, but there is much to entertain us. Entering Peterborough through its suburb of Fletton on the Huntingdon border, we cross the River Nene by a wide concrete bridge which takes the place of four predecessors. Here men have been crossing the river since Godfrey of Croyland threw his wooden bridge across in 1308. Greatly astonished he would be could he see the titanic strength of this viaduct bridging the river and the railway. It is of five spans, and is 442 feet long. We must expect that the banks of the river below will be transformed into a park to keep company with the lovely natural spaces of the city round about.

On our right as we leave the bridge is the classical Custom House with a lantern roof, and a little farther on is the best modern building in Peterborough, the Town Hall, with a bold portico of Corinthian columns and a lofty stone lantern rising above the roof of a long brick and stone building. It has shops below, and over them the civic business of the city and the district is carried on. In the Council Chamber are 17th century portraits of Sir Humfrey Orme and his wife, he having been chief man of the city in the time of Charles Stuart; he saw himself carried through the streets in effigy by the Parliament soldiers after they had destroyed the grand tomb he had set up for himself in the cathedral.

The street runs on through a medley of buildings until it divides in roads well lined with trees, for it is the pride of the city to keep this touch with nature. Hereabouts we find the modern home of the King’s School, founded by Henry the Eighth in 1541 and carried on in the minster precincts till the end of last century. The 20 poor boys of Tudor days, “both destitute of the help of friends and endowed with minds apt for learning,” have grown into 200.

There is a little medieval work to be seen in the cellars of the Angel Hotel, an interesting entrance to the Swan Inn, and an 18th century block of almshouses in Westgate. One of the most interesting buildings is the museum in Priestgate, a 19th century infirmary bought by Sir Malcolm Stewart to house the collection of the Peterborough Natural History, Scientific, and Archaeological Society. It seems that a boy’s hobby began this admirable museum, He was a lad of ten, Master John Bodger, who collected local things of interest in boxes and kept them in his bedroom until his father gave him a room in a cottage near his home. The boy’s collection grew until it was recognised as a local museum in 1880, and he looked after it nearly 60 years from then; he gave 70 years of his life, indeed, to building up this splendid place. Here are old Dutch dolls, children’s clothes of many generations, a Noah's Ark with a hundred occupants, and jolly examples of the monkey on a stick which delighted every boy before our century changed the face of toyland. Here also is the chair of that heaviest man in England, Daniel Lambert, who lies in the churchyard of Stamford Baron; and there are two more of the ancient doors in which Northamptonshire is so rich, two 11th century doors from the Abbot’s Prison.

Stone Age, Bronze Age, Roman, Saxon, and medieval days, have all their own exhibits. A Roman hunting cup has a lifelike hound in full chase carved on it, and there is a charming miniature bronze figure of a Roman soldier on horseback. On a bronze Saxon brooch is a perfectly wrought cat's head. In a room given up to an astonishing variety of things made by French prisoners in Napoleon’s day is a model of a guillotine, a model of an 84-gun ship, and many exhibits of much ingenuity and skill, including dainty things made from the simplest materials with the crudest tools — a lady’s work cabinet, jewel cases, clocks, and spinning wheels.

There is a Mary Queen of Scots Room in which is a piece of needlework she made at Fotheringhay, and some tiles and other fragments from the castle.

Many good paintings and drawings hang on the walls. On the stairs are two portraits of Oliver Cromwell and many prints of old Peterborough, some showing the Wortley Workhouse, now the Westgate Almshouses. A delightful watercolour by Turner shows the cathedral front. Birket Foster is represented by a noble beech tree and other works, William Steer by a view of Bridgenorth, Walter Sickert by an early painting of Porte St Denis, Muirhead Bone by his Spanish Chapel, and Flandrin by St Mark’s at Venice. Peterborough’s own artist engraver, Thomas Worlidge, born here in 1700, shares a room with poor John Clare. Worlidge, who lies at Hammersmith, had three wives and 32 children, but in spite of his domestic cares he became famous for his etchings in the style of Rembrandt, and is represented here by two oil portraits and hundreds of beautiful prints.

John Clare is represented by many manuscripts, some very neat, some in scrawling penmanship, some original letters he wrote to friends and patrons; and by the dictionary and the Bible he used, the Bible containing his autograph. The two oldest buildings in the town next to the cathedral stand as good neighbours, the Church of St John the Baptist and the old Market Cross, over which a chamber was built in 1671 to commemorate the Restoration of Charles the Second, the space under its open arches having been used as a butter market; it has dormer windows in the curved gables of the roof, and the royal arms and four painted shields on the east front. St John’s Church was built in the 15th century, when the people complained that they could not attend their parish church on account of floods. Much of the materials were brought from St Thomas’s Chapel, and from a chapel that has disappeared on the east of the minster.

The south porch is delightful, with a stone vaulted roof, and sitting on the gable is the heraldic antelope of Henry the Fourth, during whose reign the Church was built. The porch has three lofty arches, two of them to allow processions through the churchyard without interference. The bosses in the roof (which has a room over it) are carved with great detail, one showing the Annunciation, another the Crucifixion.

The clerestoried nave has seven bays with slender pillars, and in the aisles the medieval windows have modern tracery. In the tower hang 16th century embroidery pictures of the Crucifixion done in gold thread on a dark background, and there is a fine lifesize painting of Charles Stuart which has been rescued from a grocer’s shop. It is undoubtedly the work of a great artist, and has been attributed to Van Dyck. An elaborate triptych on the altar shows Our Lord in Majesty, with gilded figures in niches. The sanctuary is panelled, and there are four oak screens of fine craftsmanship, with excellent stalls and poppyhead benches. In the Lady Chapel is a marble monument to members of the Wyldebore family, and on a wall one of Flaxman’s finest works, a memorial to William Squire showing him with his wife on a medallion, a graceful figure representing Grief leaning on an urn.

The church has some fine windows, one with four lovely figures of the Madonna, Elizabeth, Hannah, and the Shulamite woman; another with four bishops is very rich in a jewelled setting; a Kempe window of David with his harp and the kings offering their gifts at Bethlehem; and the east window full of gorgeous colour showing Christ and the Disciples on the Sea of Galilee, with the Miraculous Draught of Fishes. The old chest in the vestry comes from the year 1569 and was carved with the Crucifixion in high relief, but it has lost the original figure of Our Lord.

So this small but great city keeps some of its good companions through the ages, yet has nothing to compare with the chief glory of it all, for there is hardly anything in England that can compare with the solemn and beautiful temple which brought Peter’s Borough into being so very long ago.

Flickr.

There it stood as the centuries went by, majestic, solemn, wonderful, yet almost solitary through the long generations of medieval England, for (except that Henry the Eighth thought so much of it that he made it a cathedral with a diocese) nothing happened round about this small cathedral city until the railway came and Peterborough began its rise from a country place with a few thousand people to the status of an industrial centre of the Midlands and a population approaching 50,000. We may imagine that but for the railway Peterborough would be today a place like Southwell, a cathedral of great splendour with a village gathered about its walls.

Yet it has known exciting days. The first Saxon settlement was burned out by the Danes, coming like Nazis with fire and sword across Mercia. Abbey after abbey they left in ruin, Crowland, Thorney, Ramsey, Ely, and Medeshamstede. The good Archbishop Dunstan encouraged the Abbot to build again, and a new Saxon church arose and was dedicated in 972. A wall was built round the settlement and a keep within it, and this little new town gave itself a new name; it called its church St Peter’s and the town St Peter’s Burgh. Abbot Leofric became so powerful that he ruled five abbeys at once, and the minster grew so rich in his time (the time of Edward the Confessor) that the little town was known as the Golden Borough. The brave Abbot marched with King Harold and meant to fight at Hastings, but he fell sick and was brought home again, and here he died on the third day after the battle that ended Saxon England and made the Conqueror king.

It was in these troubled days that Hereward the Wake, the last Saxon squire to resist the Conqueror, gathered little hosts of Danes and attacked the abbey, carrying off its treasure, burning the houses, but sparing the church. He was that Hereward whom Charles Kingsley made into a hero for every English lad, and he declared that he only wished to save the treasure of the abbey from the Normans. However that may be, the church that Hereward had spared was burned down in the generation after him, and in 1117 John of Sais began the building that we see, ranking with those imperishable glories of Norwich and Durham and Tewkesbury. It remained an abbey for nearly nine centuries from the days of Abbot Saxulf, and then came Henry the Eighth and took it over from John Chambers, the abbot who was a man of peace and “loved to sleep in a whole skin and desired to die in his nest.” Some abbots the imperious tyrant broke to pieces, but Abbot Chambers he rewarded for his docility, making him first Bishop of Peterborough.

We come to four gateways as we walk towards the cathedral, the great west gateway of the Minster precincts, the medieval gateway into the Bishop’s garden, the Tudor gateway to the Deanery, and the Norman gateway into the Cloister Court. The great west gateway, with the 14th century chancel of St Thomas of Canterbury beside it, is the finest of all the monastic buildings now standing. It is Norman and was built by Abbot Benedict, but has a 14th century front with a moulded arch. On each side of the lovely entrance arch is a Norman arcade with a doorway in it. One doorway leads into what remains of the King’s Lodging in ancient days, another brings us to an upper room once a chapel and now a classroom. The vaulted Norman chamber on the ground floor was used by the abbots as a prison and remained the town gaol until the middle of last century, having still the old door with a formidable bolt which opened into the condemned cell.

Abbot Godfrey’s medieval gateway into the gardens stands out from a row of modern buildings on our right as we approach. It is 32 feet deep with arcading on its inner walls, and a vaulted roof supporting the Knight’s Chamber. On both faces of the gateway are three figures in niches, those on the north being Edward the Second between an Abbot and a Prior, those on the south Apostles. The gateway into the deanery grounds on the left of the green in front of the cathedral is richly carved with Tudor devices, having been set up in 1510; the church on a tun over its smaller arch is a play on the name of Abbot Kirkton.

The Norman gateway into the cloisters (called Laurel Court) is reached by a narrow passage to the right of the cathedral. The cloisters were a great square with 168 yards of walks, and had windows with painted glass, but they are now a ruin. The west wall has a Norman arch remaining in its solid masonry. The south wall has two elegant pointed doorways, one having a round arch richly carved with a band of frogs and queer devices, and a tympanum with reptiles carved on each side of a quatrefoil. The effect of the small arch within the deep mouldings of the medieval arch is delightful, and this doorway is known as Heaven’s Gate.

Here are two doorways leading from the cloister into the cathedral, the Canon’s and the Bishop’s. The Canon’s doorway is Norman, the Bishop’s 13th century. The Norman doorway, impressive with a flight of steps and four columns at each side, has outer arches carved with fleur-de-lys and zigzag with two plain arches between. The medieval doorway has three elegant columns supporting its 13th century arches.

The Refectory stood behind the south wall of the cloister court, and in the bishop’s garden are some of its carved remains. There are many arches and fragments of old monastic buildings, the most striking being the tall graceful arches of the Infirmary, with an arcade of the l3th.century standing free in space. In the middle of the Cloister is a Norman well to which the white-robed monks would come for water. It was lost for centuries and has been discovered in our time. The mouth of the well was closed by a huge gravestone, but a depression in the turf led workmen to excavate, whereupon they found three steps leading to the water, and square walling showing fine Norman tooling.

It is a noble view of the walls of the cathedral that the cloisters give us, with graceful Norman arches by the hundred, stately windows of all our building centuries, and the solid and dignified central tower crowning it all. Here we see every age of this great cathedral except the Saxon; and it is an impressive spectacle, for these walls are crowded with the masterly strength and grace of the round arches of the 12th century, the delightful decorated parapet of the 13th, and stately windows with the simplicity of the 13th, the decorative development of the 14th, and the rich tracery of the 15th.

Few cathedrals have more delightful exteriors, and Peterborough is remarkable for three things the traveller sees before he comes inside, three additions to this Norman fane (at the middle and the ends) that do not spoil it, but enhance its glory. One is the central tower which, still on its Norman foundations, was raised to its battlements in the 14th century and last century was taken down and rebuilt stone by stone. Another is the lovely 15th century building enclosing the apse and is still called the New Building. It gives a delightful aspect to the east end of this great place, lengthening the cathedral by many feet, its fine walls pierced with 13 windows and crowned with a richly decorated parapet. Twelve massive buttresses hold up these walls, crowned by seated figures believed to represent the Apostles, and all much worn by the winds and rains of 500 years. The third great addition since Norman days is the incomparable west front, for the Normans had no great front to their building but left it for the 13th century to add. The main stages of the cathedral therefore cover four centuries, the main structure 12th century, the west front 13th, the central tower 14th, the east end walls 15th.

It is the marvellous west front which remains forever in the memory of all who behold it. Looking at this front across the grassy space the traveller’s mind runs back to Salisbury and Wells. It has the same sense of something rare and wonderful, something majestic, and with a strength that has kept it where it is for 700 years, yet with a soaring lightness that holds us spellbound by its enchantment. William Morris thought of it all when he wrote his Earthly Paradise:

I who have seen

So many lands, and midst such marvels been,

Can see above the green and unburnt fen

The little houses of an English town,

Cross-timbered, thatched with fen-reeds coarse and brown,

And high o’er these, three gables great and fair,

That slender rods of columns do upbear

Over the minster doors, and imagery

Of kings and flowers no summer field doth see,

Wrought in these gables.

It is a true image that the poet gives us of this west front, with its appealing beauty, its variety within a scheme of ordered symmetry. The whole mass is superb, with no suggestion of weight about it. There must be well over a mile of slender columns in these three noble arches soaring 81 feet high, and outside and above them rise lovely towers and gables and turrets adorned with delicate arches, wheel-windows, pierced arcading, carved pinnacles. and impressive statues. We wonder that so delicate a thing can have survived the buffetings of our English weather for six or seven hundred years and show so little sign of weariness or age. Professor Freeman called it “the noblest conception of the old Greek translated into the speech of Christendom,” and truly it is one of the grandest fronts in Europe. It completes with Gothic splendour the mighty work of the Normans behind it.

The great minster is 158 yards long, and of this 130 yards was built by the Normans in the space of 80 years. They left the west end unfinished, and in the next generation the English builders crowned it with these great towers and arches, so linking the work of the Conqueror’s men with that of the English builders who were to crown this island with such wonder for the next 300 years. The three stupendous arches of the front are crowned with delightful gables, the wide sweep being extended and completed by a slender tower on each side. The columns of the arches are unattached to the west wall of the cathedral, which the English builders covered with doorways, windows, and arcading, giving the arches a rich background. Over a century later (about 1370) the builders set a porch in the central arch rising halfway to the top. It may have been desirable as a support to the great piers, but the work was done with no suggestion of an afterthought, for this fine and delicate structure in no way spoils the dazzling spectacle.

The porch has delightful towers on each side, rising in two storeys enriched with niches and arcading, and above the arched doorway is a great traceried window crowned with an embattled roof. The porch runs back to join the arch of the main doorway into the minster, and has side arches opening into the space between the west front and the inner west wall. The vaulted roof has carved bosses, one of which is thought to be unique; it is a Trinity, and shows the Father with a beardless face holding the Risen Christ, with the Holy Spirit appearing in the form of a dove and seeming to be speaking to the Father.

Soaring up the towers and running across the gables of this front, and set in the spandrels of the great arches, are scores of smaller arches, some with windows, some with ornament, some with statues of benefactors and apostles. The base of each gable is filled with a rich arcade framing four windows and three apostles, with another apostle in the top of each of the three gables, completing the Twelve. St Peter presides in the centre. In the middle of each gable is a beautiful wheel-window, the central one with eight spokes, the others with six. Each of these round windows is set between two niches with statues of kings in them, so that each gable has four apostles and two kings. The niches in the spandrels of the great arches have twelve statues of benefactors of the minster, so that there are 30 figures in all. They are all very vivid, though some are badly battered by the wind and rain. The expression on the face of St Peter is remarkably good; he is giving his blessing with his right hand and has two keys in his left.

All three gables are crowned with a finely decorated cross, and between the gables are delightful octagonal turrets through which we see the sky. There are similar turrets on the bell-tower rising behind the front. The two towers belonging to the west front are crowned with pinnacles and soaring spires. It is the turrets and pinnacles of these western towers which add much to the feeling of lightness and delicacy of this great structure.

The central doorway which brings us in is divided by a noble pillar rising from a richly carved base on which a monk is being tortured by demons, a sculpture put here 700 years ago, apparently to encourage moral discipline in all who come into this fine place. The west wall pierced for this doorway has five 13th century windows filled with 15th century stone tracery, and arcading covers the wall running beyond the clustered piers of the arches and round the graceful sides of the towers. The arched door by which we enter has opened and shut for 700 years to admit every traveller who has come this way; it is carved with foliage on the capital of its central post, and its cross-pieces still have the ornament put there by the 13th century carpenter. We open this ancient door and are thrilled to find ourselves in Norman England. All about us is a spectacle unsurpassed, and only equalled in our island by the Norman splendour of Norwich, Durham, and Tewkesbury.

It is the simplicity of this vast place that strikes us first. The severe beauty of it all rises up to the triforium and the clerestory, the mighty columns bearing tier on tier of round arches of various sizes and groupings (single arch, double arch, triple arch as they rise), admirably proportioned and graduated so that we have the same feeling of lightness and grace that comes to us at the West Front. It is Norman at its purest and best, strength without a sense of over-bearing weight.

We notice that the English builders of the towers rising above the western transept could not but pay tribute to this Norman splendour by building in keeping with its style; they even used the Norman arches in the upper windows on each side, and used round arches for the frames of three doorways. We are standing where Norman hammers and axes were resounding eight centuries ago, and well may we wonder at it all, for this vast nave, begun in 1117, was finished before the century was out and is truly as magnificent as anything made by hands can be. The massive piers have clustered columns about them and arches of three orders, almost plain, with simple capitals; the great arches of the triforium are carved and have a pair of smaller arches set in each; and stately half-columns rise between the arches to the top of the lofty three-arched clerestory, touching the famous painted roof which crowns the longest, widest, and loftiest Norman nave in England.

Fitting it is that such a nave should have such a roof, for it is unique in England, the only Norman roof in any of our cathedrals; the wood is Norman and the painting English. There are only a very few surviving Norman timbers in our churches, and only one or two roofs among them, but nowhere is anything so spectacular as this. It is 204 feet long and 35 feet wide, and is divided into diamonds. In each diamond is a painted figure which has been there since about 1220, though the roof was repainted in 1834. The figures are sacred and grotesque, and worthy of another restoration. Here, among kings, queens, and minstrels, is Peter with the keys, and among the grotesque scenes are a monkey carrying an owl and riding backwards on a goat, a mother entertaining her child with a red cup and ball, a man with the head and feet of a donkey, and a lion dancing to an ass playing a harp. It is believed that the roof was made flat by the Normans but has since been raised and given sloping sides.

It was at the time of the raising of the ceiling that the Lantern Tower was restored in the 14th century, its east and west arches being made higher and pointed — the only alteration of the Norman work. The Norman arches of the transepts were not touched, however, and these superb structures, each with four bays, are as the Normans saw them, with simple arcading round the walls below the windows. Each transept has chapels, three in the south and one in the north. The southern chapels are dedicated to St Oswald, St Benedict, and St Kyneburga with St Kyneswith (the two Castor saints); in the Oswald Chapel is a stone stairway leading to an upper chamber. The northern chapel is dedicated to St Ostry. The beautiful wooden screens enclosing all the transept chapels are 15th century. In the west wall of the south transept is a richly carved 14th century doorway into a Norman chamber, with a stone vaulted roof, which is now the Sacristy, and in the north wall of the north transept is a rare Norman doorway, with a tympanum of scale-work, leading to the triforium.

But we have come into the transepts forgetting a glorious spectacle on the way, for it happens at Peterborough that the oak choir-stalls are in the two bays of the nave before the crossing. Modern, they are in striking contrast to their massive and severe environment. The stalls are richly traceried and canopied, the canopies being octagonal and in three stages, and each canopy crowned with a niche for a carved figure. There are 44 of these figures, all given by friends or by the Freemasons of England, and most of the statues are of people associated with the minster.

These are the names of the figures, beginning at the dean’s stall and going east on the south side. The dean’s stall has St Paul and St Andrew above it, and going east are: The patron saint, Peter; the first Saxon abbot, Saxulf; abbots from 971 to 1496, in this order: Adulf, Kenulf, Leofric, Turold (appointed by the Conqueror), Ernulf, Martin de Bec, Benedict (builders of the nave) Martin of Ramsey, John of Calais (builder of the cloisters), Richard of London (builder of the north-west tower), Adam of Boothby, William Genge, Richard Ashton (who began the New Building), and Robert Kirton (who finished the New Building). Next come three bishops (Towers, White, Magee) and three deans (Patrick, Saunders, Perowne).

On the north side of the stalls are these: King Wolfere and King Ethelred on the Vice-Dean’s stall, and then: King Peada, founder of the monastery; Abbot Cuthbald, Saxon; King Edgar of Mercia and his queen; Abbot Brando, 1066; Hereward his nephew, the great patriot; John de Sais, who started the choir; Abbot Hedda, slain by the Danes; Robert of Lindsey, with a model of the west front which he saw built; Godfrey of Crowland, with a model of the palace gateway; William Ramsey, abbot; Prior William Parys, builder of the Lady Chapel, now gone; St Giles, with the hind that took refuge in his cell; Hugh Candidus, chronicler and prior of the monastery; Abbot Overton; Catherine of Aragon; Dean Cosin; Prebendary Gunton; Bishop Marsh; Bishop Davys; Dean Monk; Dean Argles.

There are smaller figures tucked away in the carving of the canopies, from the Old and New Testaments; and on the two western stalls are carved panels of much interest. Four on the south represent the miracle by which the arm of St Oswald was preserved, this having been one of the relics of the monastery; on the north are four panels telling the story of Ethelwold, the great church builder of Peterborough and Winchester.

We have now completed the nave and may cross into the choir proper, looking up on our way into the vaulted roof of the Lantern Tower, with its painted medieval carving. The central boss shows Our Lord holding an orb, and other bosses have the symbols of the Evangelists. The transept roofs on each side are original, but are not painted. The roof of the choir is of wood to match the nave roof, but is 15th century and flat, carved and painted with bosses of the Crucifixion, the Devil with a wooden leg, three fishes, three lilies, and angels on medallions. The ceiling of the apse is painted to show Christ as the true vine and the disciples as the branches.

The coloured roof of the choir looks down on a tessellated pavement of a thousand rainbow hues, the patterns varying as we go east to the baldachino, which rises 35 feet and stands on a dais; it is of alabaster from Derbyshire and is a memorial to Dean Saunders, given by his children. From the four marble columns at the corners of the baldachino spring decorated arches with mosaic spandrels, and in canopied niches stand the Four Evangelists. The central panel at the front is a figure of Our Lord, and at the back in the same position is St Peter. The mosaic floor of the choir, with the wooden throne and the pulpit, were given by Dean Argles, who was here for 43 years; and in memory of him are the iron screens enclosing the choir, fine pieces of craftsmanship.

The throne is raised on three steps with a lofty canopy and a spire. On the sides are Peter and Paul, and on the book-rest are symbols of four Virtues - Temperance, Wisdom, Fortitude, and Justice. On the lower tier of the canopy are six figures of abbots and bishops: Saxulf, the first Abbot, Cuthbald, John de Sais, Benedict, Hugh of Lincoln with his swan, and John Chambers, last abbot and first bishop. In the upper tier are four bishops: Dove, Cumberland, Kennett, and Magee. The oak pulpit is also very elaborate. Round the base are arcading and four niches with abbots: John de Sais with the model of the apse, Martin de Bec, William of Waterville, and Walter of St Edmunds. Round the pulpit itself are three preaching scenes, with four saints in canopied niches dividing them: Peter, Paul, James, and John. The three scenes are attractively grouped, showing Abbot Saxulf converting the Mercians, Christ sending out the Apostles, and Peter preaching after Pentecost.

The choir has four bays, and it is interesting that all the tympana of the recessed arches under the main arcade of the triforium have different varieties of ornament. In two of these we see round holes pierced through the stone, the far-off beginning of tracery. The great bronze lectern (which must long outlast the wooden lectern in the nave) has a medieval bronze eagle on its original base, given to the minster by two men of the monastery, Abbot Ramsey and Prior Malden, of the 15th century. It may have been from this lectern that an angry Cromwellian soldier seized the big velvet-covered Bible now seen in the glass case in the nave. The story is that he took also a prayer book, some silver, and the altar candlesticks, and that when he showed them in triumph to his colonel the officer sent him back with his loot. In the choir aisles are two interesting fragments of ancient timber, one Norman — a pair of thin wooden pillars from the time when the English style was displacing the Norman, for below the Norman carving are gilded 13th century capitals cut with foliage. These are in the Ostry Chapel entered from the north aisle; in the south aisle hang three miserere seats with carving probably belonging to the original choir-stalls.

From either of these choir aisles we come into the 15th century’s great contribution to the cathedral, the New Building enclosing what is probably the finest Norman apse in the kingdom, with five bays divided by clustered shafts rising to the roof. The tracery in the upper windows is 14th century, and the three eastern arches were opened to the ground when the apse was enclosed by the splendour of the new East end, in the golden age of English architecture.

The New Building is in the style of the famous King’s College Chapel at Cambridge, and the eye is instantly drawn to the marvellous fan tracery of its roof, a wondrous spectacle. The roof is supported on two fine piers, richly carved arches, and the twelve outside buttresses crowned with the Apostles. It is the supreme wonder of this perfect little building, so filled with light from its great windows. The stone fans are like fine lace, and worked in among them are huge bosses of the lions of England and crowns pierced with arrows. The walls are arcaded below the windows, the arches being finely carved, and on the great entrance arch from the south choir aisle are many small devices, among which we read the last exultant verse of the Psalms, “Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord.” Everywhere it is evident that the 15th century craftsmen building this lovely place felt that nothing but the noblest work of man would do.

Here, in the newest part of the cathedral, the oldest treasure lies. It is a great sculptured stone believed to be Saxon, with six full-length figures on each side and primitive ornament on its roof-like top. It is said that it is the shrine made to commemorate the massacre by the Danes of Abbot Hedda and his monks in 870, but this has been questioned, and it is possible that it may be earlier work still, part of the shrine of St Kyneburga brought here with her remains in the 11th century. The sculpture is distinctly like that of a Saxon figure preserved in Castor church. All these twelve figures are crowned with a halo, and the halo round the head of Our Lord is marked with a cross. The shrine has been out in the winds and rains for centuries and is much worn, but it is a little masterpiece.

But if we would go back to the far-off Saxon beginnings of this place we come down the steps near the south-west pier of the lantern tower. The foundations of the transepts and the choir were found when this pier was rebuilt in 1883, and down these steps we may descend to view them. We may kneel in the very place where Hereward the Wake was made a knight, and where he would kneel through his vigil. It is the most thrilling spot in Peterborough. Here are fine stones believed to be part of the first Saxon church, and coffin lids with handsome crosses by Saxon masons. Fragments of carving from the church are worked into the pier, and other pieces of charred stone and timber from here are preserved behind glass in an aumbry of the south choir aisle, opposite the lovely 13th century piscina.

As we enter this south choir aisle we come upon the magnificent Norman arch for a tomb in which three abbots were laid, and here still lies the figure of one of them, said to be Abbot Andrew, laid to rest about 1200. It is one of six tombs of abbots which all travellers come to see, four more in this aisle, and a sixth in the aisle on the north of the choir. It has not been possible to identify two of the abbots, but Alexander of Holderness is known by a metal plate found on his coffin; we can see the plate with fragments of the abbot’s boots and clothing in a case in the nave. Alexander died in 1226 and has a very elaborate canopy. John Chambers, the last abbot and the first bishop, had his image carved in stone during his lifetime, and here it remains, much worn. Abbot Benedict, who lies in the north choir aisle, not far from a magnificent 14th century chest, is a very stately figure with his crozier ending in the mouth of a superbly carved reptile at his feet. All the six abbots hold croziers in their right hands and books in their left, and they are probably the best group of Benedictine monks in England, splendid figures in stone and marble.

This cathedral, which is not rich in monuments, has had within its keeping the bodies of two queens, tragic figures both, Catherine of Aragon and Mary Queen of Scots. No wall-monuments mark their resting-place, only two flags for each poor queen. The Queen of Scots has gone, and has a magnificent tomb in the richest chapel in the land, a few feet away from the tomb of Queen Elizabeth who signed her death warrant. Queen Catherine lies under a marble stone put here by the Catherines of England, Ireland, Scotland, and America in 1895. But the flags of England and Aragon are all the glory that is here to mark the grave of one of the most pathetic women in the world, first wife of the imperious Henry the Eighth, first victim of his wrath, though happily our royal butcher spared her life. As we stand by the grave of this much-wronged lady, stranger in a strange land, we may remember the words which Shakespeare makes her say as she lay dying:

When I am dead

Let me be used with honour; strew me o’er

With maiden flowers, that all the world may know

I was a chaste wife to my grave; embalm me,

Then lay me forth; although unqueened, yet still

A queen, and daughter to a queen, inter me.

Mary Queen of Scots was buried here by night, and an old pamphlet tells us that the body was brought from Fotheringhay in a coach with about a hundred men attending. Queen Elizabeth paid £321 l4s 6d for the funeral, which was followed by a formal procession through the city the next day. The coffin borne through the streets in the procession was empty though the fact was not known to the people; it was empty because the actual coffin with the body was so heavy that it could not have been carried. It weighed nearly half a ton. It was let into the grave by candlelight, and four officers attending broke their white staffs and threw them into the grave. Two Scottish flags hang on the piers to mark the place from which King James removed his mother’s body to Westminster Abbey in 1612.

Perhaps the most famous of all the varied memorials is the curious picture of Old Scarlett which hangs on the west wall of the nave. He was the verger who buried the two queens, and it was his boast that he had buried the whole population of the city twice over. He lived from 1496 to 1594 and his whole life was bound up with the cathedral.His picture, which is not the original but a copy made in 1747, shows him holding a spade, a pickaxe, keys, and a whip, and at his feet is a skull, grim symbol of his office. Under the portrait are 12 lines of rhyme. In the parish registers of St John’s Church it is recorded that there was paid to Old Scarlett “being a poor old man, and rising often in the night to toll the bells for sick persons, the weather being grievous, and in consideration of his good service, towards a gown to keep him warm, 8s.”

The minster would be much richer in shrines and tombs but for the destruction of the Civil War; but one richly carved 15th century shrine remains by the wall of the apse, just inside the New Building. It is believed to be the tomb of a kinswoman of St Kyneburga and St Kyneswith, the Christian daughters of the pagan King Penda. She is known as St Tibba, and is supposed to have been the patron saint of hunters, having a frieze of carved animals and birds on her shrine. It is thought that the shrine was once the reredos of one of the cathedral’s 22 altars, and it is said that the stone now resting on the altar of St Oswald’s Chapel is from another of these altars. Also in the New Building is a ruined fragment of the 17th century monument to Sir Humfrey Orme who had it erected in his lifetime and saw it in ruin. Near it Thomas Deacon, who founded a school at Peterborough which still bears his name, reclines lifesize on his 18th century tomb. There is a wall-monument to Bishop Cumberland who died in 1718, and a tablet of 1695 to Roger Pemberton, whose epitaph has a line of Greek from Homer: “The race of men is as the race of leaves.” Modern figures on tombs in the New Building are of Dean Ingram with a long beard, Bishop Clayton of Leicester in the more severe style of modern art, and there is a portrait head of Frederick Cecil Alderson who died in our own century after being chaplain to two monarchs; he wears a mortar board and his medallion is encircled by a bronze wreath.

In the south choir aisle is the white marble memorial of Archbishop Magee with a lifesize portrait of Bishop Mandell Creighton near it. Bishop Creighton lies in St Paul’s, having been Bishop of London, but he was six years bishop here; his epitaph is a little unfortunate in saying that he tried to write true history. Archbishop Magee lies in the burial ground here, and his epitaph describes him as one of the outstanding figures of last century. Unfortunately he is too often remembered by one of the stupidest sayings of the century — that he would rather see England free than sober. Edith Cavell and her teacher are both remembered in the nave by bronze tablets on piers. Nurse Cavel1’s portrait is in relief with a tablet saying that she was a pupil at Laurel Court School, and her teacher’s tablet tells us that Margaret Gibson was the blind Principal of the School for 40 years and the first woman to receive the freedom of the city. On the west wall of the nave is a bronze relief of a soldier known as the Lonely Anzac; he was Thomas Hunter, and died in Peterborough during the First World War, this memorial being shared with Peterborough by the citizens of his home town in New South Wales. Close by, on the south arm of the western transept, are the names of the men of St Peter’s Training College and the Old Boys from the King’s School who fell in the First World War, and on the opposite wall, in the Baptistry, is a tribute to King Peada who founded the first monastery. The font basin is 700 years old and was rescued from a garden.

The only old glass at Peterborough is a collection of fragments from the l4th and 15th centuries in the central windows of the apse; in it we can recognise St Peter receiving the keys from the Master. The windows have no special merit, but one in the south transept is by Rossetti, a vivid piece of colour showing the lowering of Joseph into the pit by his jealous brothers. The brother letting Joseph down is remarkable for having a head like the artist’s wife, with her mass of red hair. A window in the Oswald Chapel has Our Lord on the Cross between St Leonard and St Crispin; and in the New Building are five stained windows in memory of Dean Barlow (with groups of Jews and Gentiles below the figures of Peter and Paul, and angels with a scroll saying, “Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel”); Dean Butler; Dean Davys; Canon Twells, who wrote At Even, ere the sun was set; and Canon Alderson, with models of the cathedral and two churches he ministered in. The west window is in memory of men who fell in the South African War, and has two rows of five lights, with Paul, Peter, and Andrew, King Peada, and Bishop Ethelwold in the top row, and St George, St Michael, St Alban, Josiah, and Gideon below.

The cathedral library is in the room over the great west porch and in it is one of the rarest treasures from the 13th century, the Swapham Cartulary; in it is the receipt for ten shillings paid for its return by a soldier in the Civil War. The library has also a 14th century Bible with a delightful illumination of angels on Jacob’s Ladder.

The city has little history apart from the cathedral, but there is much to entertain us. Entering Peterborough through its suburb of Fletton on the Huntingdon border, we cross the River Nene by a wide concrete bridge which takes the place of four predecessors. Here men have been crossing the river since Godfrey of Croyland threw his wooden bridge across in 1308. Greatly astonished he would be could he see the titanic strength of this viaduct bridging the river and the railway. It is of five spans, and is 442 feet long. We must expect that the banks of the river below will be transformed into a park to keep company with the lovely natural spaces of the city round about.