ST ANDREW. A cathedral was established at Soham by St Felix in the early C7. It was destroyed by the Danes and never rebuilt. Its site is supposed to have been on the E side of the main village street opposite the church. Cruciform church of the late C12. But to the eye, as one approaches the church, it is Perp of a very ambitious kind. The tower and the N view with East Anglian flushwork are what will be remembered. The interior on the other hand is dominated by the earlier remains, especially the four arches of the crossing. They are plain, double-stepped and pointed, except for the W side of the W arch on which Late Norman and Early English decoration is lavished, a three-dimensional kind of crenellation with slanting sides to the merlons and various dog-tooths. Plain and pointed also the arches from the aisles into the transepts, and one-stepped and pointed those of the four-bay arcades. These rest on alternatingly circular and octagonal piers with many-scalloped capitals. The masonry of the transepts is supposed to belong to the same date, and that of the chancel to the C13. Of the C13 also the Double Piscina in the S transept with shafts and arches. The next phase of importance is the Dec style of the early C14. To this belongs the chancel in its present form with a five-light E window that has rich flowing tracery* and the S windows. Dec also the S doorway and the (renewed) S aisle and larger S transept windows. C14 probably the Sedilia too (ogee arches and a framing with a fleuron frieze), and perhaps the addition to the arcade of a W bay separated from the others by a stretch of wall. After that comes the contribution of the Perp, and that is above all the W tower. This is called the Novum Campanile in 1502, when it was probably under construction. It was no doubt a replacement of the crossing-tower. It is of four stages, with diagonal buttresses, a flushwork frieze at the base, a very big four-light W window (renewed), an immensely tall tower arch, and a gorgeous top with stepped battlements and pinnacles decorated with flushwork. At the same time the N transept and N aisle were remodelled with Perp windows, a N chancel chapel was added (arch from the chancel with fleurons) and also a N porch, the latter with flushwork decoration in the battlements and with pinnacles. The porch has inside handsome Perp wall panelling (cf. Isleham, Little Chishall) and a roof on head-corbels. The clerestory also is an addition of the late Middle Ages, and in connexion with its erection the nave received its beautiful roof which is constructed with alternating hammerbeams with figures of angels and castellated tiebeams carrying ten queen-posts each. - ROOD SCREEN, CHANCEL STALLS, CHANCEL PANELLING, and COMMUNION RAIL - all Gothic of 1849 (designed by Bonomi of Durham). - PARCLOSE SCREEN to the N chancel chapel. Perp ; good. Two-light divisions with broad ogee arches and Perp tracery above. Pretty cresting. The uprights are shaped as buttresses. - CHANCEL STALLS with simple misericords; under the tower. - BENCH-ENDS, many, with poppy-heads, also seated beasts, the head of an abbot etc. - PAINTING. Chancel N wall; figure of a bishop; C14. - STAINED GLASS. C15 bits of figures etc. in the Vestry. - MONUMENT. Long ogee-headed recess in the N transept N wall.

* Inside l. and r. of the E window are two niches with tiny bits of flushwork enrichment.

SOHAM. It was one of the English cradles of Christianity, where Felix of Burgundy came to found his abbey on high ground above the plain. Here they laid him to rest, and a few years later St Etheldreda founded her abbey at Ely, and both abbeys flourished till both were destroyed by the Danes. Soham Abbey was never raised again, but the little town has a fine view of the cathedral which grew out of Etheldreda’s abbey at Ely, standing on the hill at the end of the five-mile Causeway built to link the two towns soon after the Conquest.

The fruitful orchard land of what was once Soham Mere lies to the west. The sails of a windmill turn at each end of the straggling town and between them lies the splendid church built nearly 800 years ago. Its oldest remains are still its chief glory within, but it is to the 15th century that Soham owes its grand tower, rising above the fenland like a symbol of faith that many waters cannot quench. It rises 100 feet high, with lovely battlements and pinnacles, and looks down on two beautiful medieval porches. The aisles have cornices carved with roses, and there are heads at the south doorway. There is an impressive array of arches inside, four of them believed to have supported the central tower of the 12th century church. The western arch has rich mouldings and capitals of that period, and most of the simpler arches of the nave are of the same age. The tower arch soars impressively, and an arch of the 15th century, leading into a chapel, has two rows of flowers in its mouldings, embattled capitals, and grotesque animals on each side. The chancel has 13th century walls, the south transept has a 13th century piscina, but the richly carved sedilia is 14th. A brave array of angels, sitting and kneeling, praying and holding shields, looks down from the grand old roof.

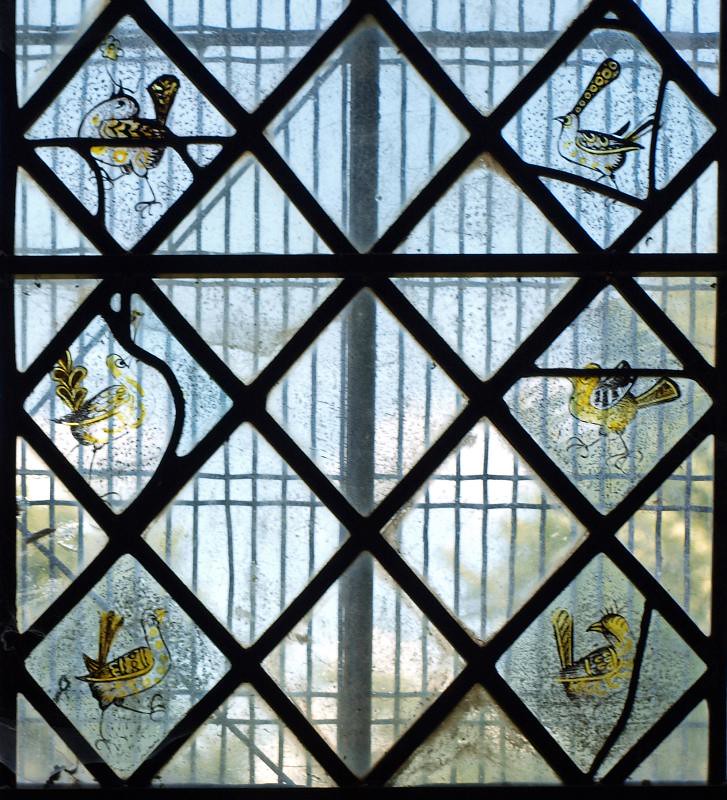

In one of the chapels, to which we come by an ancient door with iron bars and a massive lock, is an old stone altar, and medieval glass with angels, birds, and flowers. Among a wealth of ancient woodwork in the church is a 15th century screen, its tracery tipped with roses, animals, and grotesque faces; an eagle and a queer man are peeping out above the entrance. There are 15th century benches with carved heads on which is an angel, a bishop, and a flying lizard, and on some 600-year-old stalls in the tower are carved seats with the quaint fancies of the medieval craftsmen. On one of the walls is an old painting of a bishop, and hidden behind the organ is the 16th century monument of Edward Bernes, showing his 15 children kneeling; he and his wife are lost, An inscription in the chancel tells of John Cyprian Rust, “scholar and friend of children,” who shepherded his flock here for 53 years.

In the churchyard lies a very old man whose inscription says curiously, “Dr Ward, whom you knew well before, was kind to his neighbours and good to the poor,” and not far from him is the grave of Elizabeth D’Aye, unknown to most of those who come into this churchyard, yet a woman of much interest, for her mother was the only grown-up daughter of Cromwell’s best son, Henry. Elizabeth had come down in the world. Her mother, Elizabeth Cromwell, had married an officer in the army, William Russell of Fordham, who lived far beyond his income, kept a coach and six horses, and gathered so many creditors about him that it was said to be fortunate that he died. His widow, so far from trying to retrieve the shattered fortunes of her family, struggled to keep up appearances, and it is recorded that she took as many of her 13 children as she could and went up to London, where she died of smallpox caught by keeping the hair of two of her daughters who had died from it.

Her daughter Elizabeth married Robert D’Aye of Soham, who also spent a good fortune, and was so reduced that he died in the workhouse. Richard Cromwell’s daughter appears to have come to widow D’Aye’s assistance, but she died in the grip of poverty, leaving behind her still another Elizabeth, who married the village shoemaker of Soham, a man of honesty and good sense who rose to be a high-constable. Well may the biographer of the House of Cromwell be moved by the thought of his descendants begging their daily bread. “Oh, Oliver,” says he, “if you could have seen that the gratification of your ambition could not prevent your descendants in the second and third generation from falling into poverty, you would surely have sacrificed fewer lives to that idol. How much are they to be pitied!”

There was born at Soham in 1748 a leather-seller‘s son named James Chambers, who must have broken his father’s heart by choosing evil ways and living the life of a ne’er-do-well while trying to be a poet. He lived to be nearly 80, when he died at Stradbroke, and for most of his life he appears to have been a roaming gipsy, making acrostics of people’s names if they would give him a meal. He wrote some of his verses in Soham workhouse, but none of them are to be matched with the fine work that has come from many of these houses of adversity. There are references to him in old books and papers, but he has been forgotten as a good-for-nothing, and the best reference we have found to him was written by Mr Cordy of Worlingworth in Suffolk:

A lonely wanderer he, whose squalid form

Bore the rude peltings of the wintry storm:

Yet Heaven, to cheer him as he passed along,

Infused in life’s sour cup the sweets of song.

Mr Cordy made an appeal for him and found him a cottage, which was furnished so as to encourage him with his poems. But it was no use; in a month or two he was off again, preferring a bed of straw to a couch of down.

Flickr.

The fruitful orchard land of what was once Soham Mere lies to the west. The sails of a windmill turn at each end of the straggling town and between them lies the splendid church built nearly 800 years ago. Its oldest remains are still its chief glory within, but it is to the 15th century that Soham owes its grand tower, rising above the fenland like a symbol of faith that many waters cannot quench. It rises 100 feet high, with lovely battlements and pinnacles, and looks down on two beautiful medieval porches. The aisles have cornices carved with roses, and there are heads at the south doorway. There is an impressive array of arches inside, four of them believed to have supported the central tower of the 12th century church. The western arch has rich mouldings and capitals of that period, and most of the simpler arches of the nave are of the same age. The tower arch soars impressively, and an arch of the 15th century, leading into a chapel, has two rows of flowers in its mouldings, embattled capitals, and grotesque animals on each side. The chancel has 13th century walls, the south transept has a 13th century piscina, but the richly carved sedilia is 14th. A brave array of angels, sitting and kneeling, praying and holding shields, looks down from the grand old roof.

In one of the chapels, to which we come by an ancient door with iron bars and a massive lock, is an old stone altar, and medieval glass with angels, birds, and flowers. Among a wealth of ancient woodwork in the church is a 15th century screen, its tracery tipped with roses, animals, and grotesque faces; an eagle and a queer man are peeping out above the entrance. There are 15th century benches with carved heads on which is an angel, a bishop, and a flying lizard, and on some 600-year-old stalls in the tower are carved seats with the quaint fancies of the medieval craftsmen. On one of the walls is an old painting of a bishop, and hidden behind the organ is the 16th century monument of Edward Bernes, showing his 15 children kneeling; he and his wife are lost, An inscription in the chancel tells of John Cyprian Rust, “scholar and friend of children,” who shepherded his flock here for 53 years.

In the churchyard lies a very old man whose inscription says curiously, “Dr Ward, whom you knew well before, was kind to his neighbours and good to the poor,” and not far from him is the grave of Elizabeth D’Aye, unknown to most of those who come into this churchyard, yet a woman of much interest, for her mother was the only grown-up daughter of Cromwell’s best son, Henry. Elizabeth had come down in the world. Her mother, Elizabeth Cromwell, had married an officer in the army, William Russell of Fordham, who lived far beyond his income, kept a coach and six horses, and gathered so many creditors about him that it was said to be fortunate that he died. His widow, so far from trying to retrieve the shattered fortunes of her family, struggled to keep up appearances, and it is recorded that she took as many of her 13 children as she could and went up to London, where she died of smallpox caught by keeping the hair of two of her daughters who had died from it.

Her daughter Elizabeth married Robert D’Aye of Soham, who also spent a good fortune, and was so reduced that he died in the workhouse. Richard Cromwell’s daughter appears to have come to widow D’Aye’s assistance, but she died in the grip of poverty, leaving behind her still another Elizabeth, who married the village shoemaker of Soham, a man of honesty and good sense who rose to be a high-constable. Well may the biographer of the House of Cromwell be moved by the thought of his descendants begging their daily bread. “Oh, Oliver,” says he, “if you could have seen that the gratification of your ambition could not prevent your descendants in the second and third generation from falling into poverty, you would surely have sacrificed fewer lives to that idol. How much are they to be pitied!”

There was born at Soham in 1748 a leather-seller‘s son named James Chambers, who must have broken his father’s heart by choosing evil ways and living the life of a ne’er-do-well while trying to be a poet. He lived to be nearly 80, when he died at Stradbroke, and for most of his life he appears to have been a roaming gipsy, making acrostics of people’s names if they would give him a meal. He wrote some of his verses in Soham workhouse, but none of them are to be matched with the fine work that has come from many of these houses of adversity. There are references to him in old books and papers, but he has been forgotten as a good-for-nothing, and the best reference we have found to him was written by Mr Cordy of Worlingworth in Suffolk:

A lonely wanderer he, whose squalid form

Bore the rude peltings of the wintry storm:

Yet Heaven, to cheer him as he passed along,

Infused in life’s sour cup the sweets of song.

Mr Cordy made an appeal for him and found him a cottage, which was furnished so as to encourage him with his poems. But it was no use; in a month or two he was off again, preferring a bed of straw to a couch of down.

Flickr.

No comments:

Post a Comment