The painting is every bit as good as expected - perhaps even more so - but, despite a great location, I was disappointed with the building as a whole. Its diminutive exterior should be pleasing but isn't, to my eyes at least; it's all angular and jutting but that might be the Surrey vernacular to which I am unaccustomed.

Inside it's spartan, smaller than you'd expect and rather dull. Having said that it does have probably the most important mediaeval wallpainting in the country: which is nice.

I don't have the relevant Pevsner, Surrey's a long way from home, but more info on the Doom can be found here.

Chaldon. One famous thing draws the traveller to this beauty spot among the Surrey Downs, one of the finest ancient possessions of its kind in the land; but there are other treasures old and rare and quaint. They are gathered in the little church with more than 1000 years of history behind it, set quietly at home with Nature, its companion an ancient farmhouse with a bargeboard 600 years old.

The church is high and short and wide, with a tower and shingled spire rising up from a corner by the porch. The outlines of the nave and chancel are as they were in the century of the Conqueror, and some of the masonry from that time is still here. From the next century come one of the aisles and the chapel. The other aisle was built on two centuries later.

One of the curious possessions of Chaldon is in the chancel, next to an arched tomb 600 years old, a remarkable tablet with a face in the form of a flaming sun. It does not seem to be anybody’s memorial, yet it has a message for all from 1562, and says:

Good Redar warne all men and women while they be here

to be ever good to the poore and nedy.

The cry of the poore is extreme and very sore.

In thys worlde we rune oure rase:

God graunte us to be with Christ in tyme and space.

It is possible that the initials on the tablet refer to John and Ellen Richardson, who were living here in Elizabeth’s reign and may have wished to preach this little sermon.

From a century later comes the fine pulpit, one of the few known to have been made in the Commonwealth. It bears the name of Patience Lambert, who had seen her husband buried in the nave below.

In the porch hangs the oldest bell in Surrey, and one of the oldest in the country, its voice still heard. It was certainly made before 1250 and may be several decades earlier, and it tells us that it is Paul’s bell. Its fellow, Peter’s Bell, was here 400 years ago, but is now lost; the two may well have been ringing in the Norman church.

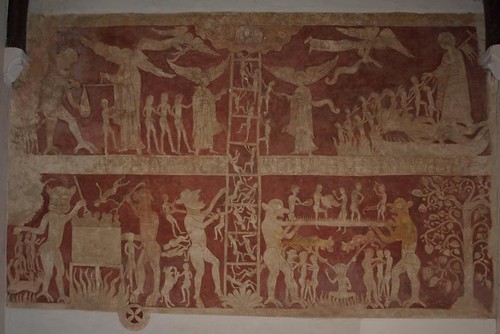

The chief of all Chaldon’s treasures is counted among the rare possessions of England, adorning the oldest wall of the church with a little Norman window above it. It is the great painting of the Ladder of Salvation, leading up to heaven and down to hell, an extraordinary achievement of Norman art thought to be the work of a monk 750 years ago. Preserved by a coat of whitewash (under which it was found in 1870), it is in wonderful condition, something to fascinate old and young today as it has been fascinating the people of Chaldon for centuries.

This great picture, 17 feet long and 11 feet high, is filled with astonishing figures and scenes. As old as the Dream of Jacob, and perhaps much older, is the idea of the ladder of salvation with the ascending and descending figures. Halfway up the ladder is a band of cloud stretching the length of the picture. It is painted in the conventional manner of olden days and is the dividing line between the salvation of souls and the torments of hell. With the ladder it forms a great cross, cutting the picture into four parts.

At the right of the lower division is the Tree of Life. Its formal design is one of the clues that help us to guess the date of the picture, which was painted about 1170, the year St Thomas of Canterbury was murdered. A serpent is hiding among the branches. It is here that the story begins, for we are first reminded of the Fall of Man.

The remainder of the lower division shows the torments of hell. Next to the tree two huge demons hold up the bridge of spikes, over which cheating tradespeople, bearing symbols of their trades, are timidly walking. This punishment is another very old idea going back almost as far as thought can reach. The nightmare bridge over Gehenna was believed to be as narrow and sharp as a razor. A blacksmith is one of the unfortunate people in the act of crossing it. His hand is raised with a hammer, and he is ready to strike a red-hot horseshoe which he holds in pincers. Villagers of 700 years ago probably knew at once that he was the blacksmith of the well-known story who was condemned to forge a horseshoe without an anvil while crossing the bridge. The man who holds a bowl so carefully at the other end was probably a milkman who had given short measure to his customers, for the bowl is painted yellow and contains white fluid. He has been given the impossible task of carrying it across the bridge; and it looks as if he will soon be crying loudly over spilled milk in the awful abyss below, where a usurer sits among roaring flames on a fiery seat. A big purse of money hangs from his neck and three bags of gold are suspended from his waist.

Here again is a subject of countless stories familiar to the village people of mediaeval times. The usurer has no eyes, and gold coins, which he is forced to count, are pouring from his mouth. Two demons leap above him and prod at his head with their pitchforks. Fire is raging in the left division below the bar of clouds, where we see a great cauldron full of suffering souls. Two frightful demons are prodding them with pitchforks. The one on the left is holding a group of souls above a demon wolf gnawing at their feet, indicating that they are dancers, who were specially denounced by the monks of those days. A dog is about to bite a lady’s hand, the allusion being, no doubt, to the wealthy lady who pampered her dogs and fed them with the rich food she should have given in charity to the poor. Clinging frantically to the bottom of the Ladder of Life are more lost souls, most of them falling down, others being relentlessly picked off with a two-pronged fork by a monster demon showing his teeth. He is handing a victim over his shoulder to the demon of the cauldron.

It is a relief to look up to the top of the ladder, where angels help the good souls to reach the heaven of their aspirations. On the right, above the Tree of Life, is a dramatic rendering of the Descent into Hell. Satan lies bound, and Christ stands over him thrusting the staff of his banner into his mouth, while Adam and Eve and the souls of the patriarchs are set free.

The Weighing of Souls (on the left of the ladder) is one of the most interesting pictures in this old English Book of the Dead. Here is another idea found in ancient religions, particularly in that of the Egyptians. The Archangel Michael holds the scales. Another angel seems to be carrying a tablet with a record of good deeds. Satan, with his tongue out, is dragging along a group of souls by a rope, and slyly tries to press down the scales on his side and thus secure another victim. One fortunate soul is being lifted up to heaven by an angel.

In all England there is not a more complete example of 12th century painting than this. It is one of the most precious of our national possessions; only fragments are missing. In planning the picture the artist appears to have forestalled Dante, who used many of the same ideas in his Divine Comedy about 60 years after this Chaldon scene appeared. Here the artist has broken away from the Byzantine tradition of representing people conventionally. Although very few of the animated figures have faces they are full of expression and are painted in natural attitudes. The complicated subject is treated with great simplicity. The ease with which the painter has handled his brush, and the skill with which he has arranged the ideas he has taken from the legends and stories of his day, reveal him as an artist of no mean talent.

To the Chaldon people this painting must have been of tremendous interest. They could neither read nor write, but the picture’s story was something they could understand.

The church is high and short and wide, with a tower and shingled spire rising up from a corner by the porch. The outlines of the nave and chancel are as they were in the century of the Conqueror, and some of the masonry from that time is still here. From the next century come one of the aisles and the chapel. The other aisle was built on two centuries later.

One of the curious possessions of Chaldon is in the chancel, next to an arched tomb 600 years old, a remarkable tablet with a face in the form of a flaming sun. It does not seem to be anybody’s memorial, yet it has a message for all from 1562, and says:

Good Redar warne all men and women while they be here

to be ever good to the poore and nedy.

The cry of the poore is extreme and very sore.

In thys worlde we rune oure rase:

God graunte us to be with Christ in tyme and space.

It is possible that the initials on the tablet refer to John and Ellen Richardson, who were living here in Elizabeth’s reign and may have wished to preach this little sermon.

From a century later comes the fine pulpit, one of the few known to have been made in the Commonwealth. It bears the name of Patience Lambert, who had seen her husband buried in the nave below.

In the porch hangs the oldest bell in Surrey, and one of the oldest in the country, its voice still heard. It was certainly made before 1250 and may be several decades earlier, and it tells us that it is Paul’s bell. Its fellow, Peter’s Bell, was here 400 years ago, but is now lost; the two may well have been ringing in the Norman church.

The chief of all Chaldon’s treasures is counted among the rare possessions of England, adorning the oldest wall of the church with a little Norman window above it. It is the great painting of the Ladder of Salvation, leading up to heaven and down to hell, an extraordinary achievement of Norman art thought to be the work of a monk 750 years ago. Preserved by a coat of whitewash (under which it was found in 1870), it is in wonderful condition, something to fascinate old and young today as it has been fascinating the people of Chaldon for centuries.

This great picture, 17 feet long and 11 feet high, is filled with astonishing figures and scenes. As old as the Dream of Jacob, and perhaps much older, is the idea of the ladder of salvation with the ascending and descending figures. Halfway up the ladder is a band of cloud stretching the length of the picture. It is painted in the conventional manner of olden days and is the dividing line between the salvation of souls and the torments of hell. With the ladder it forms a great cross, cutting the picture into four parts.

At the right of the lower division is the Tree of Life. Its formal design is one of the clues that help us to guess the date of the picture, which was painted about 1170, the year St Thomas of Canterbury was murdered. A serpent is hiding among the branches. It is here that the story begins, for we are first reminded of the Fall of Man.

The remainder of the lower division shows the torments of hell. Next to the tree two huge demons hold up the bridge of spikes, over which cheating tradespeople, bearing symbols of their trades, are timidly walking. This punishment is another very old idea going back almost as far as thought can reach. The nightmare bridge over Gehenna was believed to be as narrow and sharp as a razor. A blacksmith is one of the unfortunate people in the act of crossing it. His hand is raised with a hammer, and he is ready to strike a red-hot horseshoe which he holds in pincers. Villagers of 700 years ago probably knew at once that he was the blacksmith of the well-known story who was condemned to forge a horseshoe without an anvil while crossing the bridge. The man who holds a bowl so carefully at the other end was probably a milkman who had given short measure to his customers, for the bowl is painted yellow and contains white fluid. He has been given the impossible task of carrying it across the bridge; and it looks as if he will soon be crying loudly over spilled milk in the awful abyss below, where a usurer sits among roaring flames on a fiery seat. A big purse of money hangs from his neck and three bags of gold are suspended from his waist.

Here again is a subject of countless stories familiar to the village people of mediaeval times. The usurer has no eyes, and gold coins, which he is forced to count, are pouring from his mouth. Two demons leap above him and prod at his head with their pitchforks. Fire is raging in the left division below the bar of clouds, where we see a great cauldron full of suffering souls. Two frightful demons are prodding them with pitchforks. The one on the left is holding a group of souls above a demon wolf gnawing at their feet, indicating that they are dancers, who were specially denounced by the monks of those days. A dog is about to bite a lady’s hand, the allusion being, no doubt, to the wealthy lady who pampered her dogs and fed them with the rich food she should have given in charity to the poor. Clinging frantically to the bottom of the Ladder of Life are more lost souls, most of them falling down, others being relentlessly picked off with a two-pronged fork by a monster demon showing his teeth. He is handing a victim over his shoulder to the demon of the cauldron.

It is a relief to look up to the top of the ladder, where angels help the good souls to reach the heaven of their aspirations. On the right, above the Tree of Life, is a dramatic rendering of the Descent into Hell. Satan lies bound, and Christ stands over him thrusting the staff of his banner into his mouth, while Adam and Eve and the souls of the patriarchs are set free.

The Weighing of Souls (on the left of the ladder) is one of the most interesting pictures in this old English Book of the Dead. Here is another idea found in ancient religions, particularly in that of the Egyptians. The Archangel Michael holds the scales. Another angel seems to be carrying a tablet with a record of good deeds. Satan, with his tongue out, is dragging along a group of souls by a rope, and slyly tries to press down the scales on his side and thus secure another victim. One fortunate soul is being lifted up to heaven by an angel.

In all England there is not a more complete example of 12th century painting than this. It is one of the most precious of our national possessions; only fragments are missing. In planning the picture the artist appears to have forestalled Dante, who used many of the same ideas in his Divine Comedy about 60 years after this Chaldon scene appeared. Here the artist has broken away from the Byzantine tradition of representing people conventionally. Although very few of the animated figures have faces they are full of expression and are painted in natural attitudes. The complicated subject is treated with great simplicity. The ease with which the painter has handled his brush, and the skill with which he has arranged the ideas he has taken from the legends and stories of his day, reveal him as an artist of no mean talent.

To the Chaldon people this painting must have been of tremendous interest. They could neither read nor write, but the picture’s story was something they could understand.

No comments:

Post a Comment