Whilst not the most exciting of interiors - it was extensively restored three times following fires in 1545, 1897 and in 1940 there was a direct hit on the north door in the summer and the following December the church was showered with so many incendiary bombs that even the cement caught alight - there is plenty of interest here. Given that only the shell, the arcade in the chancel, the outside walls and the tower survived the bombing this is a very sympathetic restoration.

Mee's entry records the pre-bombed church and is interesting as it shows what was lost to the incendiaries.

At the end of Monkwell Street is a passage opening to an avenue of trimmed planes in the churchyard of St Giles’s, Cripplegate.

Rahere the king’s jester built St Bartholomew’s and his friend Alfune built St Giles’s. That was in the reign of William Rufus, but the church as we see it has been twice rebuilt, and except for the base of the tower is mostly 400 years old. It must be for ever a place of pilgrimage for the English-speaking race.

Here one drab November day in 1674 they buried an old neighbour, giving him a “very decent interment according to his quality.” The little procession had come from a house not far away, with brother Christopher and two nephews, a few learned friends, and a “concourse of the vulgar” to say farewell to a blind old man in grey so long familiar in these streets. He was John Milton.

Here one summer’s day in 1620 there had come another small procession with a joyous purpose, for a young man from the country was marrying a merchant’s daughter from Essex; he was not yet 21, but was a man with great spirit, kneeling here in front of the altar with his bride, and his name was to ring round the world with that of the blind old man. He was Oliver Cromwell, and his bride was Elizabeth Bourchier. One day in the years that lay ahead an exiled king was to come back to his throne to find a paper at his Privy Council marked Old Mrs Cromwell - Noll’s Wife’s Petition.

This precious church was spared by the Great Fire, but it has suffered from other fires, for the City has always pressed closely round it, as the warehouses do still. It is plainly seen from Fore Street (the ancient way before the Wall), or from the churchyard, but the best view is from the vicar’s gate, where we see the tower with its fine 15th century base and its upper storey of 1684 with a wooden lantern and a fine musical peal of 12 bells which play hymns and songs every three hours.

This church with so much history has in its churchyard a visible monument of the earliest days of our history, a bastion of the Roman Wall with flowers and plants creeping out of its crevices. It is a thrilling sight. Sharing the churchyard with it is Milton’s statue, with these famous lines from Paradise Lost:

O spirit! What in me is dark

Illumine; what is low, raise and support,

That to the height of this great argument

I may assert Eternal Providence

And justify the ways of God to man.

On the pedestal are scenes in Comus and Paradise Lost. In the church is a tablet marking the grave of the poet; he lies with his father in the chancel. Near the tablet is his bust, by John Bacon.

The oldest monument that has escaped the fires of Cripplegate is that of Thomas Busbie, a rich cooper who died in 1575. His painted figure shows him in a black coat, his face full of benevolence, and his epitaph tells us that he gave the poor of Cripplegate every year four loads of the best charcoal and 40 dozen loaves.

Near him lies a man who died the year before the Armada came, before either Milton or Cromwell was born, leaving behind him the Book of Martyrs which was placed with the Bible in hundreds of churches, chained for safety. His name is on the north wall. John Foxe had saved his life by living abroad in the years of persecution, and though he might have held high oflice in the Church he lived in toil and privation, writing what he believed was true. It was his deepest conviction that religion had no place in it for cruel violence, a truth that was rarely seen in his day among any body of Christians in the land.

Here Lies Martin Frobisher

In that Tudor age they brought to this place another man who lives in history though his heart is buried far away in Plymouth; he was that plain old sailor Martin Frobisher, explorer of the North-West Passage, one of the most skilful of the men who shattered the Armada, and a hero after Queen Elizabeth’s own heart. His monument is in a dim corner of the south aisle, and has a relief of a sailing ship bristling with cannon. It was put here 300 years after the defeat of the Armada, and has on it the lines of Macaulay beginning, Attend! all ye who list to hear our noble England’s praise. On an ornate monument in the north aisle is a bust of Sir William Staines, Lord Mayor in 1800, in his chain of office.

Here also lies John Speed, the Cheshire man who spent most of his days working as a tailor in London, but whose remarkable knowledge of history won for him the friendship of Fulke Greville. It was Fulke Greville who enabled him to take up the task of drawing maps of all the counties of England, and of writing their history “from Julius Caesar to King James.” He was the first man to summarise all the history that was known of his country. They laid him in this church in 1629; and here we see his figure, with a book in his right hand and his left on a skull, enclosed as in a cupboard. Near him are kneeling 17th century figures of Richard and Elizabeth Smith. An Elizabethan vintner, Roger Mason, is also here, engraved on a stone panel, kneeling with his wife and daughter.

The famous Lancelot Andrewes, who was vicar here before he became three times a bishop and one of the greatest spiritual forces in the life of the Church, is remembered with an inscription. He was one of the men who made the Authorised Version, and when he passed away in 1626 Archbishop Laud wrote in his diary: “About four o’clock in the morning died Lancelot Andrewes, the Great Light of the Christian Church.” Another vicar here was Samuel Annesley, whose daughter Susannah became the mother of John Wesley.

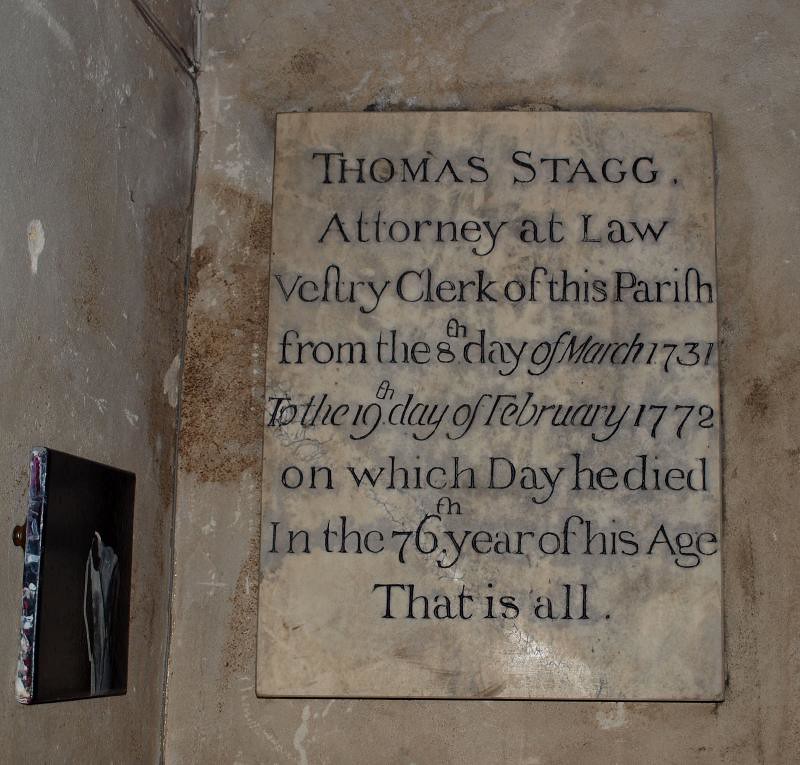

That is All

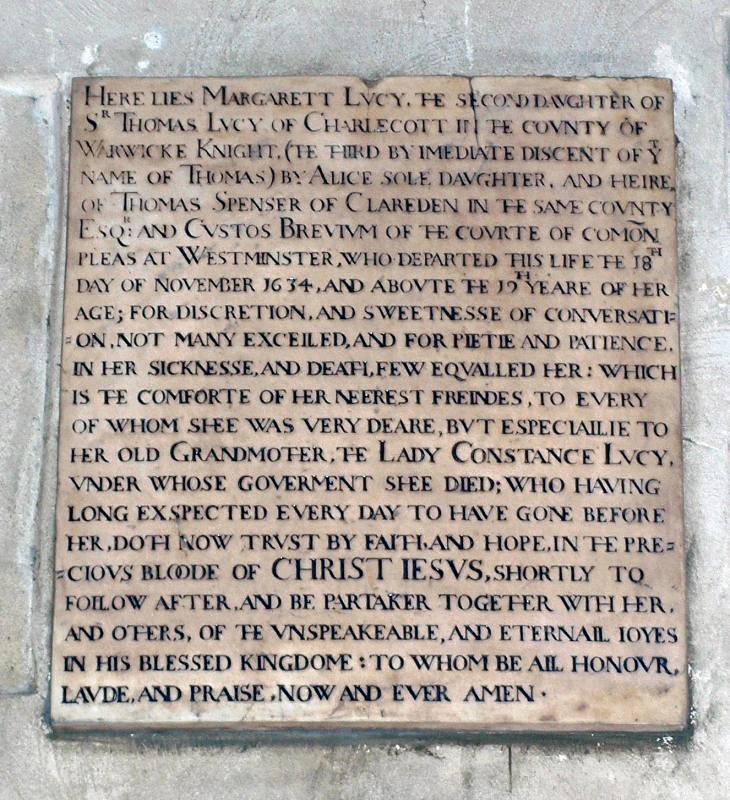

Over the north door is a fine marble monument to Edward Harvist, one of King James’s gunners, who is shown facing his wife across a prayer desk. Edmund Harrison, embroiderer to three Stuart kings, has a tablet saying he “left the troubles of this world” in the year of the Fire, and just below is a panel engraved with the kneeling figure of Charles Langlie, a Tudor brewer. In the north aisle is a curious and striking monument with a figure of a girl in a shroud rising from a coffin; it is thought she was a relative of Sir Thomas Lucy, Shakespeare’s Justice Shallow. On the south wall are little 17th century figures of Matthew and Anne Palmer, with five children. A monument by Thomas Banks shows Mrs Hands dying in the arms of her husband, a vicar here, and near this is the epitaph to Thomas Stagg, an 18th century vestry clerk, giving the date of his clerkship and his death, and adding, That is all. The church has other treasures worthy of notice. The altar, the balusters of the rails, the clock with the gilt figure of Time, the pulpit with festoons of fruit and flowers, the font cover with its gilded dome, and the lectern, are all early 18th century, and it is believed that some of this woodcarving is the work of the Richard Saunders who made Gog and Magog in the Guildhall. The fine oak reredos of 1704 has modern painted panels, and the north chapel has a 17th century reredos with carved angels and paintings of Moses and Aaron. Like the 18th century doors to the north lobby, it came from a lost church. Hidden under the reredos are tiles 600 years old.

The east window is oval, with some 18th century glass. A modern window with three panels of the Nativity is in memory of Edward Alleyn, the actor friend of Shakespeare and founder of Dulwich College. Two other famous names come into the church register: Holman Hunt, whose painting of the Light of the World is known everywhere, and who was baptised here; and Daniel Defoe, whose death is recorded here although he lies in Bunhill Fields. He lived close by in the Barbican, and it is thought his book on the Plague deals with this parish. During that awful year the number of burials in this churchyard reached 800 in a week.

A large church mostly of c. 1545-50, i.e. at the end of the medieval church-building tradition. Much restored in the late C19 and again by Godfrey Allen after severe bomb damage (reopened 1960). It now serves as the centrepiece of the Barbican Estate’s main open space. Overshadowed by massive concrete forms and paved right up to the walls, it looks in its situation by the lake almost as if dismantled and brought from elsewhere; but it also anchors the late C20 environment in the wider urban context - in part by marking the true ground level, something visitors to the Estate may find elusive - and in an older history.

The church is recorded as having been built by Aelmund the priest c. 1102-15. According to Stow, the former vicarage stood on the site of an earlier church further W, but this may only have been a wayside shrine (by tradition the church marks the resting place of the body of King Edmund Martyr outside Cripplegate in 1010). The addition of guild chapels to the church on the present site in the C14 culminated in its complete rebuilding in 1390. The C16 rebuilding, following a fire of 1545, is thought to have reused the C14 plan, which tapers markedly from W to E with the tower slightly off axis. Substantial late C14 work survives in the chancel walls, better visible since cleaning in 1994. C14 work also remains in the base of the tower, which has angle buttresses to the outer corners, a big NW stair-turret and two-light windows. Brick top stage with panelled parapet and stubby pinnacles, added by John Bridges in 1682-4. Its two-light tracery differs from that of the restored lower apertures, but its forms are also late C19 and not 1680s Gothic. The pretty open cupola is a post-war restoration. Otherwise, the church was refaced in ragstone by F. Hammond (S side 1884-5, redone after the fire damage in 1897; N side 1903-5).

Inside, the nave and aisles are of seven bays with a partly projecting chancel, the ritual chancel extending also to the two bays furthest E. The stone piers have a moulding of four shafts connected by deep hollows with thin filleted diagonal shafts. The hollows continue around the arch. Aisle windows of three lights with simple panel tracery, on the N simpler than on the F. Fine shafts up to the roof between depressed-arched windows. The carving of corbels, stops etc. is renewed. The E end was much altered in the C18, and the chancel arch dates only from 1858-9 (galleries removed 1862). The Perp E window is post-war, based on late C14 traces discovered during restoration (replacing a large azil-de-boeuf window of 1704 with glass of 1791 by Pearson). A two-light N chancel window was opened up at the same time; the answering S window remains blocked. The post—war roof is arch-braced. Traces survive of the ROOD—LOFT DOORWAY (S wall), battered double SEDILIA with near-equilateral arches (restored with salvaged Roman tiles), and PISCINA in a square-headed surround. They look late C14.

Few FITTINGS survived the war and the church has been refurnished, partly with items from elsewhere. The big new W GALLERY by Cecil Brown has tall Composite columns. On it an ORGAN CASE, from St Luke Old Street, of 1733 by Jordan & Bridge; rebuilt in 1970 by Noel Mander, with casework of 1684 from St Andrew Holborn (behind). - FONT with elegant stem and bowl with acanthus leaves, and domed COVER, with pilasters and garlands, both from St Luke Old Street. - SWORD REST. C20. - STAINED GLASS. E window, Crucifixion by A. K. Nicholson Studios, 1957. - Armorial W window by john Lawson (Faithcraft Studios), 1968. - SCULPTURE. Four busts of c. 1900 (Milton and Defoe by Frampton; also Cromwell and Bunyan), on loan from the Cripplegate Institute. - Bronze statue of Milton (who is buried here) by Horace Montford, 1904. It formerly stood N of the church, facing the old line of Fore Street (its battered pedestal, designed by E.A. Rickards, stands outside, minus Montford’s reliefs). - MONUMENTS. Thomas Busby d.1575, damaged bust from a once large monument. - John Speed d. 1629. Bust, damaged in the war, restored 1971 in a replica of part of the old surround. Attributed to John & Matthias Christmas (Aw). - Elizabeth de Vallingin d.1772 (part), with circular plaque of a female mourner, pyramid and urn. - Thomas Stagg d.1772, tablet abruptly inscribed: ‘that is all’. - Bust of John Milton, by the elder Bacon, given by Samuel Whitbread in 1793. The pedestal has a little carving of the serpent and apple. - Bust of Sir William Staines d.1807, by Charles Manning, from a large monument destroyed by bombing.

Around the church is a brick-paved area planted with trees, partly on the site of the pre-war churchyard. The late C19 GAS LAMPS, scattered about like saplings, were brought here from Tower Bridge. Some early C19 tombstones of rounded-coffin type, with other slabs reused as seats. The huge monolith of the Stanier vault (S side) is worth looking at. A church hall is accommodated below ground level E of the chancel.

Flickr.

The church is recorded as having been built by Aelmund the priest c. 1102-15. According to Stow, the former vicarage stood on the site of an earlier church further W, but this may only have been a wayside shrine (by tradition the church marks the resting place of the body of King Edmund Martyr outside Cripplegate in 1010). The addition of guild chapels to the church on the present site in the C14 culminated in its complete rebuilding in 1390. The C16 rebuilding, following a fire of 1545, is thought to have reused the C14 plan, which tapers markedly from W to E with the tower slightly off axis. Substantial late C14 work survives in the chancel walls, better visible since cleaning in 1994. C14 work also remains in the base of the tower, which has angle buttresses to the outer corners, a big NW stair-turret and two-light windows. Brick top stage with panelled parapet and stubby pinnacles, added by John Bridges in 1682-4. Its two-light tracery differs from that of the restored lower apertures, but its forms are also late C19 and not 1680s Gothic. The pretty open cupola is a post-war restoration. Otherwise, the church was refaced in ragstone by F. Hammond (S side 1884-5, redone after the fire damage in 1897; N side 1903-5).

Inside, the nave and aisles are of seven bays with a partly projecting chancel, the ritual chancel extending also to the two bays furthest E. The stone piers have a moulding of four shafts connected by deep hollows with thin filleted diagonal shafts. The hollows continue around the arch. Aisle windows of three lights with simple panel tracery, on the N simpler than on the F. Fine shafts up to the roof between depressed-arched windows. The carving of corbels, stops etc. is renewed. The E end was much altered in the C18, and the chancel arch dates only from 1858-9 (galleries removed 1862). The Perp E window is post-war, based on late C14 traces discovered during restoration (replacing a large azil-de-boeuf window of 1704 with glass of 1791 by Pearson). A two-light N chancel window was opened up at the same time; the answering S window remains blocked. The post—war roof is arch-braced. Traces survive of the ROOD—LOFT DOORWAY (S wall), battered double SEDILIA with near-equilateral arches (restored with salvaged Roman tiles), and PISCINA in a square-headed surround. They look late C14.

Few FITTINGS survived the war and the church has been refurnished, partly with items from elsewhere. The big new W GALLERY by Cecil Brown has tall Composite columns. On it an ORGAN CASE, from St Luke Old Street, of 1733 by Jordan & Bridge; rebuilt in 1970 by Noel Mander, with casework of 1684 from St Andrew Holborn (behind). - FONT with elegant stem and bowl with acanthus leaves, and domed COVER, with pilasters and garlands, both from St Luke Old Street. - SWORD REST. C20. - STAINED GLASS. E window, Crucifixion by A. K. Nicholson Studios, 1957. - Armorial W window by john Lawson (Faithcraft Studios), 1968. - SCULPTURE. Four busts of c. 1900 (Milton and Defoe by Frampton; also Cromwell and Bunyan), on loan from the Cripplegate Institute. - Bronze statue of Milton (who is buried here) by Horace Montford, 1904. It formerly stood N of the church, facing the old line of Fore Street (its battered pedestal, designed by E.A. Rickards, stands outside, minus Montford’s reliefs). - MONUMENTS. Thomas Busby d.1575, damaged bust from a once large monument. - John Speed d. 1629. Bust, damaged in the war, restored 1971 in a replica of part of the old surround. Attributed to John & Matthias Christmas (Aw). - Elizabeth de Vallingin d.1772 (part), with circular plaque of a female mourner, pyramid and urn. - Thomas Stagg d.1772, tablet abruptly inscribed: ‘that is all’. - Bust of John Milton, by the elder Bacon, given by Samuel Whitbread in 1793. The pedestal has a little carving of the serpent and apple. - Bust of Sir William Staines d.1807, by Charles Manning, from a large monument destroyed by bombing.

Around the church is a brick-paved area planted with trees, partly on the site of the pre-war churchyard. The late C19 GAS LAMPS, scattered about like saplings, were brought here from Tower Bridge. Some early C19 tombstones of rounded-coffin type, with other slabs reused as seats. The huge monolith of the Stanier vault (S side) is worth looking at. A church hall is accommodated below ground level E of the chancel.

Flickr.

No comments:

Post a Comment