I very nearly made a major error at St George, locked, keyholders listed, by almost not seeking out the key - the light was beginning to go and the exterior did not particularly inspire me. Luckily, however, I saw a likely window in the south aisle and changed my mind and so did not miss one of the best interiors in Suffolk to date [unsurprisingly Simon Jenkins doesn't mention it, perhaps he didn't seek out the key - 1000 best churches my arse]. Here is an outstanding collection of bench ends, poppyheads, choir stalls, misericords, early C16th Flemish reliefs, a faded St Christopher and the best Hugh Easton window I've seen to date. Sadly the church is, to all intents and purposes, redundant - in that it is rarely used apart from high days and holidays - but I can't imagine the CCT will not step in at some point.

ST GEORGE. A fine Perp building, tall and aisleless, and vigorous in the simplicity of its decorative enrichments. Said to have been built by Robert Davey, who died in 1401. Flushwork chequerboarding on buttresses and parapets. Flushwork panelling on the S porch. E window of five lights with much panel tracery, nave and chancel with very tall two-light windows, also with panel tracery. The S porch has an entrance still entirely C14 in its responds and arch. One niche above the entrance. Cambered roof with tie-beams in the church. (Ceilure above the rood screen.) - FONT. Octagonal, early C14. Bowl with eight figures under crocketed gables. - SCREEN. Only the dado. Tall and traceried. The panels painted red and green. - BENCHES. Fine set with traceried ends, poppy-heads, and animals on the arms, also seated and kneeling figures. - STALLS. With close tracery on the ends and instead of poppy-heads small standing figures: a preacher in the pulpit, a deacon, a man holding a candlestick, men holding shields, etc. Traceried fronts. Also some MISERICORDS (bird, demi-figure of angel, cockatrice, etc.). - (DOOR. To the upper stages of the tower. Iron-bound in a wickerwork pattern. G. McHardy) - SCULPTURE. l. and r. of the reredos nine Flemish early C16 reliefs. - WALL PAINTING. Huge St Christopher on the N wall. The heron, the lobster, and the fishing hermit ought to be noted. - PLATE. Cup 1562; Salver 1740. - MONUMBNTS. Paul d’Ewes. By John Johnson, the contract of 1624 preserved (for £16 10s.). Stone, painted. Two kneeling wives facing one another. Between them, kneeling frontally, the husband. Children in the ‘predella’. Flat architecture ending in a flat open segmental pediment. - Sir Willoughby d’Ewes d. 1685. Handsome, with scrolly Corinthian pillars and an open pediment.

STOWLANGTOFT. It has a few moated farms (a rare distinction for any village), and a church of the 14th century rich with treasure, standing on a spot where Romans camped, and Normans built. It has its original font and part of the old screen, and wall-paintings in which we can still make out St Christopher striding through the water with lobsters and other dwellers of the deep about his feet. In one corner of the picture is a plump little cherub playing with two rabbits.

But we come to this church for its rare carvings in wood. The six misereres on the choir-stalls rank among the finest in any parish church, having intricate and delicate carvings of angels, eagles, dragons, and other birds and beasts. The crowning glory of all this work, 600 years old, is the collection of poppyheads and carved bench-ends, which are among the finest in the land. Their richness and variety can only be fully appreciated when they are seen. There are more than 60 carved figures and animals, dogs, eagles, hedgehogs, birds with human heads, a grinning cat with its tongue out, a pouter pigeon, a kilted Scot, a chemist with his pestle and mortar, a mermaid admiring her tail, a pig playing a harp, a squirrel biting a nut, and a little child kneeling at a prayer desk. These are a few of the delightfully fantastic designs in this unique gallery of medieval art.

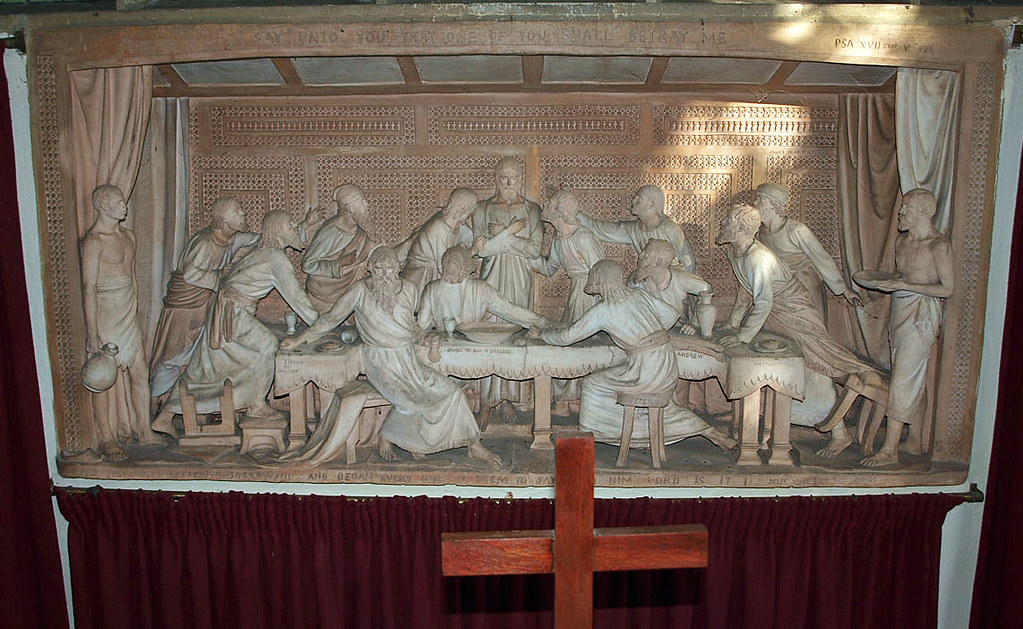

Yet this is not all. The church has been still further enriched by a wonderful series of carvings, nine groups of 15th century Flemish work representing scenes from the Last Days in Jerusalem, set on oak pedestals at the sides of the reredos. In high relief they are carved from solid oak about five inches thick. There are many figures in each group and the clear-cut finish of detail is astonishing. One rare scene is of Christ preaching to the Spirits in prison; in another the mouth of Hell is represented by the open jaws of a monster in the act of swallowing four unhappy victims. Other groups are the Agony of Gethsemane, the Road to Calvary, the Scourging, the Descent from the Cross, the Entombment, the Resurrection, and the Ascension.

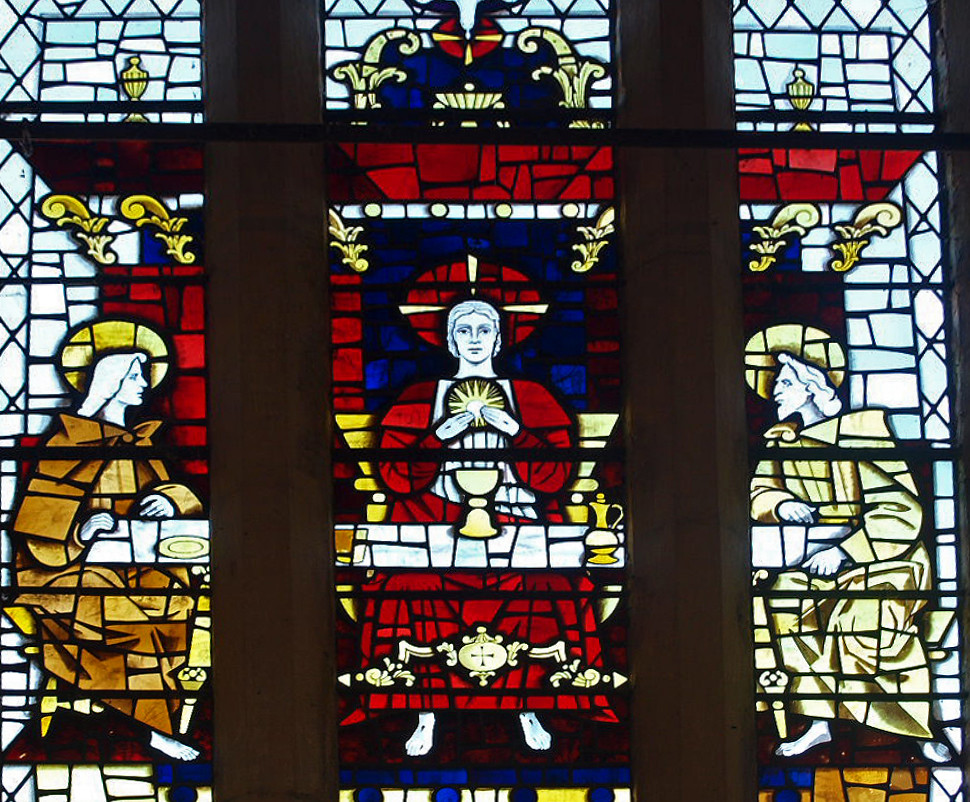

Some of the windows were painted last century by a daughter of the rector; in them are small medallions of the Beatitudes and other Bible scenes. Even the lead work of these windows was made at the rectory, where Cardinal Newman would come visiting and would probably see these windows being made. Two modern windows of the chancel have figures of Loyalty, Love, Courage, and Humility, and the alabaster reredos represents the Lord’s Supper.

A 16th century portrait brass has a knight in armour, his wife beside him with her head on a cushion. On a fine canopied wall monument is a figure of Paul d’Ewes, holding a book and kneeling with his two wives and their eight children. One of the children in the group is Sir Symonds d’Ewes, who was born at Coxden in Dorset in 1602 and spent his life in research, studying old documents and manuscripts. He began with the records of the Tower of London and his enthusiasm never wavered. It was his ambition, “if God permit, and that I be not swallowed up of evil times, to restore to Great Britain its true history, the exactest that ever was yet penned of any nation in the Christian world”; but he was inclined to over estimate his capacities, and he is chiefly remembered as a diligent copyist. A strict Puritan and a man of sterling character, he served in the Long Parliament, but was never quite happy in the stormy politics of those times, and when he was expelled by Colonel Pride, with 40 other men, he said Goodbye to Westminster for ever.