I'm ashamed to say that I was so absorbed by the roofs and other features in the abbey, open [Jenkins ****], that I completely ignored/missed the quire - this may have been due to general church fatigue, a recent ban on quire photography in cathedrals or general stupidity...I blame the latter or maybe the former.

Apart from the fan vaulting - which is astonishing - there's an abundance of interior here from a C11th priest monument to C15th glass via Christopher Webb in the Lady Chapel, John Hayward's windows, the Horsey, Digby and Leweston monuments. It's a truly rewarding building.

In 705 Sherborne was made the see of the Bishop of Wessex. The church remained a cathedral till 1075, when the see was moved to Old Sarum. The cathedral became monastic in 998 and did not cease to be monastic till 1539. In the late CI4 a church was built immediately adjacent to the abbey church, the latter’s W wall serving as its E wall. Abbeys did not like parochial duties, for which the W part of their church had to be kept publicly open. In 1540 the abbey church was sold to the town, and the parish church was then demolished. That the town kept up the whole of the abbey church instead of demolishing the E end or the W end is much to Sherborne’s credit. Selby, Cartmel, Carlisle, Tewkesbury, Christ Church Oxford (St Frideswide), Southwark did more or less the same. Bridlington, St Iolm Chester, Dunstable, Leominster, Malmesbury, Holy Cross Shrewsbury, Waltham Abbey, Worksop preserved only the nave; Bristol and St Bartholomew London, only the choir.

The present church has minor but important Anglo-Saxon features, Norman transepts and crossing, and an E.E. Lady Chapel, but is predominantly Perp. The Perp work was begun from the E c.1420-30, and by the time of a fire which occurred in 1437 the crossing had been reached. The vaulting of the E end took place c.1450. The nave was built during the last quarter of the C15.

The church is c.255 ft long. It is built of Ham Hill stone.1

The church was restored in the 1850s by R. C. Carpenter (who died in 1855) and William Slater, his partner (nave and transepts 1849-51, choir 1856-8). Later the partnership was Slater & R. H. Carpenter, and the latter restored the tower in 1884.

EXTERIOR

The examination must start at the W front, although this faces us with what looks like extreme confusion. However, the confusion is fruitful; for it tells not only of the church in whose shadow we stand, but also of its Anglo-Saxon predecessor and of the parish church of All Hallows.

THE SAXON CHURCH. The rough masonry of the w wall belongs to it, as is proved by a completely preserved doorway which must once have led into the N aisle. It is now accessible only from inside the church. It is cut through the wall without any splays, is high in proportion to its width, and is accompanied by the typical shafts l. and r. at a distance from the opening. The shafts once continued as an arch. In section they are semi circular. Excavations about 1875, and again in 1964-70, have shown that w of this Saxon wall was a westwork consisting of a tower and two side chambers or transeptal features extending further N and S than the N and S aisles. The NE corner of the extension was found in I968 and is of good and telling long and short work.2

The shaft N of the Saxon doorway belongs to the scanty remains of All Hallows.

ALL HALLOWS. It is not known when the parish church was built. The late C14 is the most likely date. What remains is the whole N wall to the height of the original window sills with the wall shafts dividing aisle bay from aisle bay, the E responds of the aisle arcades (they are of standard section), and, to the N and S of these, the responds of high arches leading into side chapels which extended N and S of the ambulatory. The springing of the S archway is still in situ. The blocked doorway into the S aisle of the church is Norman, probably of c.1120, but the interior N jamb is evidently Saxon - cf. the laying of the stones - and similar to the N aisle doorway. There is in addition a narrower C14 doorway inside the Norman one. It was inserted c.1436. The main W doorway from All Hallows into the abbey church has tracery spandrels and a quatrefoil frieze over. W window of nine lights, the two principal mullions reaching right up into the principal arch.3

THE EXTERIOR CONTINUED. The Norman church extended as far W as the Saxon church, as the S porch proves. This is Late Norman. Norman rebuilding had probably begun early in the C12 at the E end and reached the S porch only c.1170.4 The upper floor of the porch is Victorian. The monumental entrance arch has zigzag at r. angles to the wall surface and two orders of columns. The capitals are fanciful, with masks, beaded bands, and foliage. There is also small nailhead l. and r., and round the corners to the W and E are blank arches with continuous roll mouldings. Such blank arches are also inside the porch. An upper tier of them has again zigzag at r. angles. The room is rib-vaulted. The S doorway is very large. It has an inner order of continuous zigzag at r. angles, one tall order of columns, and a zigzag arch, at r. angles too. The columns of the doorway inside the building have trumpet-scallop capitals, another proof of Late Norman date.

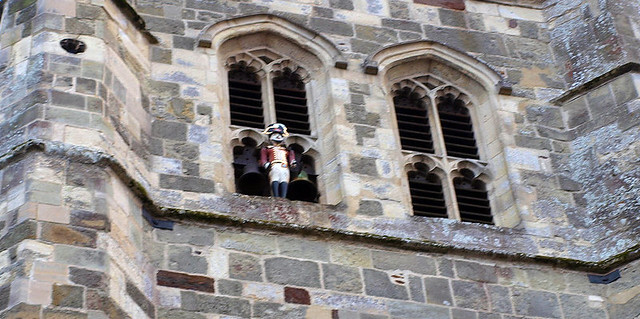

The S view of the church is well exposed and entirely Perp. The aisle windows are of three lights and the aisle has a parapet with blank quatrefoils, the first of many. The clerestory windows have steep two-centred arches, five lights with the two main mullions again reaching up into the main arch. Some of the sub-arches have straight shanks. The shallow buttresses between look Norman but are not. The S transept is evidently Norman, though the big S buttresses are Perp and so is the window. But in the E wall are exposed traces of the upper Norman windows. In the angle between S aisle and S transept is St Katherine’s Chapel, Perp too. Three-light windows and a quatrefoiled parapet. The S transept S window is of eight lights, again with the main mullions up into the main arch and again with some sub-arches with straight shanks. The Chapel of St Sepulchre is similar to that of St Katherine. The crossing tower has pairs of two-light bell-openings with a transom and Somerset tracery. Twelve pinnacles on the top. Before Carpenter there were eight. The choir S aisle has windows with depressed arches and four lights and another quatrefoiled parapet. A small doorway has leaf spandrels. The clerestory has flying buttresses and windows of six lights. They have two-centred arches, and the main mullions once more reach into them. There are also the straight shanks and sub-arches. The E window is of nine lights, the main mullions as before. More quatrefoiled parapets. The choir S aisle ends in the Chapel of St Mary le Bow. This looks curiously domestic, the reason being that this, its northern continuation, i.e. the larger part of the Lady Chapel, and the vestry block (see presently) were the Headmaster’s House of Sherborne School. The date of the conversion, 1560, is recorded on the E side. To the S are four-light mullioned windows. A multitude of shields of arms between them. Above the upper window is the coat of arms of Edward VI between twisted colonnettes.

SE of the chapel are handsome wrought-iron GATES of 1723.

The E end of the Lady Chapel was built as a war memorial in I921 to the design of Caroe. As Caroe liked his treatment of Gothic to be unexpected, he took motifs from the 1560 alterations to the Bow Chapel.

The N side of the church is less easily seen. Buildings of the school interfere, including the former monastic buildings now also belonging to the school.

The N side of the choir is like the S side. The vestry corresponding to the Bow Chapel is domestic-looking too. Three floors with mullioned windows, of six lights to the E. Of the chapel of Bishop Roger the C13 date is evident from the E window of three stepped lancets under one arch. The N transept stood to the N, against the monastic E range of the cloister. The roof-line of the dormitory is at once visible. The W and E windows are large and Perp, of six lights under depressed arches. Two transoms. The nave clerestory windows are as on the S side. But the aisle treatment is different. The windows are Victorian, but it is known that one original window had reticulated tracery, the only Dec feature of the whole church.

INTERIOR

The exterior having been treated as a perambulation, it might be useful to discuss the interior chronologically and always from E to W.

Of the ANGLO-SAX0N church some conjectures will appear presently.

NORMAN. Of the Norman choir nothing can now be seen except the plinths of the clasping buttresses of the E end visible below the stone bench in the ambulatory and some outer N walling inside Bishop Roger’s Chapel. It has three niches with continuous roll mouldings like the S porch and upper intersecting blank arcading, the colonnettes with three small scallops. Next, the crossing piers must be examined, and they are likely to be Saxon. What appears typically Saxon is the projection of the NE pier of the crossing to the NE and the SE pier to the SE, an angle of ninety degrees pre-supposing a crossing a little wider than the aisles. That is exactly the type of crossing one finds in the early C11 crossing of Stow in Lincolnshire, and also at Milborne Port in Somerset and Norton in County Durham. Equally puzzling are the nearly semi circular projections of the crossing piers into the transepts. They also do not tally in their bases and tops with the Norman work and may well be Saxon (cf. chancel arch Deerhurst, Glos.). The E and W crossing piers were rebuilt c.1850-5 by R. C. Carpenter (David Lloyd).

Clearly Norman on the other hand are the crossing piers otherwise, with their twin demi-shafts. Capitals of big, i.e. early, scallops. The E arch is now Perp, the W arch has had its shafts removed (for stalls) in the lower parts. The arches are stepped and the transept arches are stilted. There is no evidence of Perp work being higher than C12 work; on the contrary, the S transept walls (less parapet) are the same height as originally built in the C12, as the marks of the C12 weathering of its roof on the S tower face prove. The nave arch is not stilted; the transept arches are stilted because they are narrower yet reach the same height as the nave arch. The Perp crossing vault cuts into Norman lantern arcading in the tower. Seven arches, the middle one higher and wider.

The N transept has Norman walling, one odd shaft and capital exposed in the E wall and the complete arch to the N nave aisle. This also has tiny scallop capitals, except for one which has the kind of decoration like the porch capitals, i.e. may be a later alteration, as may be the roll attached to an edge of the arch. The Wykeham Chapel is Norman too. It has a straight E end and on that side and the S large upper intersecting arches. A fragment of the Norman E window also remains.

The S transept walling can be seen exposed in St Katherine’s Chapel. The arch to the S aisle is like the N arch, but all capitals are scalloped. Of the Norman nave all that can be seen is a piece of string-course on the NW crossing pier and in the E responds of the Perp piers the curve of a semi circular(?) respond. Of the aisle walling nothing is to be noticed, and the W wall - to end the Norman description - is confusing from inside as well. As has already been said, the Norman S doorway has a C14 doorway set in.

EARLY ENGLISH. This is mainly the Lady Chapel. It was originally three bays long, and Caroe’s E end cut it off. The entry from the retrochoir is marked by responds with a group of detached Purbeck shafts carrying lively stiff-leaf capitals and a finely and intricately moulded arch.5 Such capitals and shafting also for the former N and S windows. Short shafts on cornucopia-like corbels and again with stiff-leaf capitals mark the division between first and second bay. Rib-vault with a small boss and the springing of the ribs of the second bay.

The other E.E. contribution is Bishop Roger’s Chapel. but there is nothing to be remarked on inside except a good PISCINA and the Purbeck shafting of the E window, lancet lights as well as super-arch.

DECORATED. Signally absent, as has already been said.

PERPENDICULAR. This makes Sherborne what it is. Caroe was right to use it for his E bay of the Lady Chapel, and his tripartite entryarches, narrow-wide-narrow with thin piers, are a charming conceit. Above the tripartite arch is an Elizabethan (?) eight-light window, perhaps of the time of the front of the Bow Chapel. The retrochoir is fan-vaulted with many bosses; so are the choir aisles. The wall shafts are thin, but have the standard section. Panelled transverse arches W and E of the second bays from the W. The Chapel of St Mary le Bow has in its E wall a fireplace. This belongs to the alterations of 1560). The chapel itself dates probably from the C14 (cf. the S jamb of a former E window).

The choir has broad piers of complicated, unconvincing section. To the choir ‘nave’ the projection is the standard one, to the arches it is a triple shaft. The impressive thing is a broad panelled order which rises all the way up to embrace the clerestory window. There is one tier of panelling below these as well, and panelling against the E wall. The vault is a fan-vault, the earliest major one in existence (c.1450, i.e. after a fire in 1437),6 and indeed still with ribs, thin and straight as match-sticks - as if it were a lierne-vault.

The same fan-vaulting is used in the crossing. Broad panelling to the choir. The N transept is fan-vaulted too, whereas the S transept has a beamed ceiling with bosses. The Wykeham Chapel E of the N transept has a veritable primer-book fan-vault. The Chapel of St Sepulchre is lierne-vaulted, that of St Katherine again fan-vaulted (with a square of liernes in the middle). The nave aisles have lierne-vaults, the nave a gorgeous fan-vault with many bosses. The nave piers are not placed at equal distances, and it has been suggested that the narrower distances towards the W end are those of the Norman (or Saxon?) piers. The Perp piers are broad and panelled all over. Shields at the apexes of the arches (including a bishop of Exeter who ruled in 1509-19). Angel busts and fleurons along the string-course below the clerestory. The angels hold shields (including that of Cardinal Morton, who died in 1500). The clerestory windows have one tier of blank panelling below.

FURNISHINGS

From E to W, and always N before S.

LADY CHAPEL. REREDOS. A sheet of glass engraved by Laurence Whistler in 1967-8 with two cornucopias and other motifs. - CHANDELIER. The earliest example in England of the familiar brass type, inscribed 1657. It is probably Dutch import. Such chandeliers appear in innumerable Dutch C17 pictures. - STAINED GLASS. E 1957 by Christopher Webb.

RETROCHOIR. Some floor TILES.

CHAPEL OF ST MARY LE BOW. FONT. Octagonal, Perp, with a panelled stem. - Also some floor TILES. - SCREEN. Only the base is Perp. The upper part with the openwork inscription must be of c.1930. It was designed by Caroe. - STAINED GLASS. Old bits in the E and S windows.

CHOIR. REREDOS. By R. H. Carpenter, 1884, with large figures in relief by Forsyth. - STALLS. Victorian, but incorporating a series of MISERICORDS. They include (N) a man pulling his mouth open, the Last Judgement, (S) a chained monkey, a man whipping a boy, an archer, a woman beating a man. - STONE SCREENS. 1856, probably by Slater or R. H. Carpenter. - STAINED GLASS. Clerestory by Clayton & Bell, 1856-8. - PAINTING. The decoration on walls and vault is by Clayton & Bell, executed by Crace.7

NORTH CHOIR AISLE. MONUMENTS. Two of Purbeck marble to abbots. Of Clement only the head and the round arch above or behind his head is preserved. This is of c.1150, i.e. the earliest of the whole South West English series. The face is severely stylized, reminding one of Maya heads. - The other is easily C13. Shafts l. and r. of the effigy and a trefoiled arch.

SOUTH CHOIR AISLE. There is a third Purbeck MONUMENT here, yet a little later. The abbot’s head is below a pointed-trefoiled arch with a gable. There are no shafts. The arch stands on corbels, one a head, the other stiff-leaf. - Tester of a C17 PULPIT, used as a table-top.

BISHOP ROGER’S CHAPEL. Assembled here are a number of MONUMENTS, all tablets. Dominating the others is the enormous one to Carew Henry Mildmay d.1784. Drapery hanging from the top of an obelisk against which stands an urn. Medallion of his wife above the urn, his medallion against the plinth. Hutchins says it is by Thomas Carter. - John Eastmont d. 1723. Several urns, the top one in a scrolly open pediment.

CHAPEL OF ST SEPULCHRE. SCULPTURE. Wooden statue of St James, late C15. Spanish.

CROSSING PULPIT. 1899, designed by B. Ingelow and carved by James Forsyth. Ingelow was R. H. Carpenter’s partner. - LECTERN. 1869 by R. H. Carpenter, made by Potter’s of London.

WYKEHAM CHAPEL. MONUMENT. Sir John Horsey d. 1546 and his son d. 1564. Sir John Horsey bought the abbey at the Dissolution. He lived at Clifton Maybank. White stone. Tomb-chest with shields. Two recumbent effigies. Square pillars with arabesque decoration. Against the back wall the coat of arms in a lozenge (cf. Clifton Maybank, the frontis-piece of c.1535 now at Montacute in Somerset). Top with supporters and a small pediment.

SOUTH TRANSEPT. STAINED GLASS. Excellent S window with ninety-six figures. Designed by Pugin and made by Hardman; 1851-2. - MONUMENTS. John Digby, Earl of Bristol d. 1698. Signed by Nost. A vast machine, but not too large for its position. Reredos with up-curved top on two elegant Corinthian columns. Inside in front of blank arches Lord Digby, and a little lower down his two wives holding burning hearts. Two putti, decidedly too small, outside the columns. - A son and a daughter of Lord Digby, d. 1726 and 1729, have a smaller tablet without any effigies. However, the epitaph is by Pope.

NAVE. STAINED GLASS. The W window probably also by Pugin and Hardman (RCHM).

ST KATHERINE’S CHAPEL. STAINED GLASS. Many fragments are assembled here, including small whole bearded figures; C15. - MONUMENT. John Leweston d. 1584. White stone, the foot-end attached to the E wall. Tomb-chest with shields, recumbent effigies, six Corinthian columns, big top with putti. The underside of the canopy has the characteristically Elizabethan ornamental motifs of straight lines connecting circles and squares. Dr Girouard attributes the monument to Allen Maynard (cf. Longleat, Wilts.).

SOUTH AISLE. FONT. Octagonal, with on the bowl a veritable pattern book of blank Perp three-light and four-light windows. It is C19, not C15.

SOUTH PORCH. The wrought-iron GATE is of 1750 ‘to prevent indecencies’.

PLATE. Cup, 1636; Paten on foot, 1699; Flagon, 1708; Almsdishes, 1712 and 1786; Cup, 1824.

1. This piece of information and very much else I owe to Mr I. H. P. Gibb. He read the proofs for Sherborne Abbey and corrected much and improved much. For the Saxon work his help was especially precious.

2. Since this was written Mr Gibb has identified the N jamb of the blocked doorway at the W end of the S aisle.

3. The two lower rows of lights were added by R. C. Carpenter. In doing so he discovered remains of a Saxon window which originally looked out from an upper floor of the Saxon tower into the nave.

4. Mr Gibb draws my attention to the marked irregularities of the nave arcade (the N side piers stand 14 in. W of the corresponding ones on the S side and all the arches vary in width). He suggests that the Saxon arcade and clerestory survived until the C15 rebuilding, and adds: ‘Why the Perp builders retained the cores of the Saxon piers with their very irregular spacing and yet built a perfectly regular clerestory on top of them is a mystery’.

5. Mr Gibb tells me that only the S shaft of the entrance arch is real Purbeck. The other shafts are replacements in local Forest marble.

6. But Howard pointed out that the piers and clerestory windows of before 1437 told of an intended fan-vault.

7. Information from David Lloyd.

SHERBORNE. As he lay a captive in the Tower, waiting for his betrayal by the King of England, the founder of the British Empire asked his wife to bury him in Sherborne. Sir Walter Raleigh loved this place. So do we; so do all who come. It was the home of the dreamer and founder of the British Empire and it is the grave of two kings.

It has been a great place for a thousand years and more. Its beginnings were much farther back to Raleigh than Raleigh is to us. About 40 generations of men have passed this way since the Saxon bishop Aldhelm came from Malmesbury to build this church and set up this school. Some say Alfred himself found his love of learning here, and certainly his two brothers knew this place, for here they sleep, two kings before Alfred. So that we have at Sherborne the founder of this great school in Aldhelm, the foundations of our national greatness in Alfred, and the founder of our Empire in Sir Walter Raleigh. It is a high tradition.

Much there is that Raleigh himself would see here, in the streets, in the abbey, in the little hospital, and in the great house itself. Who can walk about in this place that he loved without thinking of the pity of it all? We think of that time when his doom was hastening on, when the knowledge that Raleigh was fitting out his ships set Spain thinking. Philip was not yet dead and he had not forgotten Elizabeth and the Great Armada. With such a king as James on Elizabeth’s throne the last of the Elizabethans could be hunted down. So the Spanish ambassador protested to the king against the activities of Sir Walter Raleigh and against his being free, and in the end this man who helped to scatter the Armada, the last of that incomparable group of Englishmen who spent their lives in fighting Spain, who made the English throne safe for this king to sit on and gave the English power at sea - the last of this company of immortals was handed over to Spain and betrayed by James himself. He set Raleigh free to organise an expedition and allowed him to organise it on the basis of war, and behind Raleigh’s back he gave the Spanish ambassador all the secret plans and this solemn promise to Philip: that if Raleigh offended the might of Spain he, King James himself, would send the founder of the British Empire back to be hanged in Madrid. Such things were done by our Stuart kings.

Raleigh was away a year, and when he came back to Plymouth, on a glorious summer’s day in 1618, his faithful wife was waiting for him. It must have been too much for her to bear, for Raleigh had failed. His dream had not come true, the Spaniards had attacked his unarmed men, and, bitterest news of all this woeful tale, their boy was dead.

So Raleigh met again this woman he had loved in the happy days at Sherborne, and in this desperate hour there stood beside them the kinsman who betrayed him, to arrest him in the name of the king. Spies were set to watch and trap him on the road to London, and on this journey up they passed through Sherborne. Raleigh’s heart was broken as he looked at it all, and there in this scene of his early married life, thinking of the tragedy of the faithful woman at his side, he burst out, All this was mine, and it was taken from me unjustly.

That is one of the moving memories which comes to us in this old Dorset town, this lovable and delightful place where we may walk back to medieval England when we will.

It lies in the middle of Blackmoor Vale. Surrounded by wooded hills, its pastures provide some of the richest grazing ground of the county, and it gathers about a Norman abbey, the beautiful old buildings of a famous school, a 15th century almshouse, and the ruins of a Norman castle.

In a park on one side of the little river Yeo stand the fine ruins of the castle built 900 years ago by the fighting Bishop Roger. He called it his palace, but it was as strongly fortified as any of the fortresses of the feudal barons. Queen Elizabeth gave the estate to Raleigh on hearing that he had seen and loved the fair town and the countryside on his rides from Plymouth to London, and after those days it was granted to the Digbys, who have it still. They defended it for the king in the Civil War and it was so shattered by the Parliamentary bombardment that it has remained a ruin. Cromwell is said to have undermined the north wall with the help of miners from the Mendips, and so forced its surrender.

But it was Raleigh himself who seems to have realised that there must be a new house. In the excavations that have been taking place in the ruins a flight of stone steps have been discovered which have suggested that Raleigh was making an effort to adapt the old house to his needs, but he must have given up the attempt. He wanted “the most fine house” and set to work to build it. Little could he have dreamed that in only a year or two his fine house would be taken from him and he would die a shameful death in the shadow of Parliament, betrayed by a king not worthy to unloose his shoe. A stone seat in the grounds is said to be where he sat smoking when his servant threw a flagon of ale over him, thinking he was on fire, but we do not know if the tale is true. The new house became the home of the Digbys, and after the Restoration of the Stuarts stones from the ruins were used to extend it and reconstruct it in the form of the letter H. Here William of Orange stayed after his landing, and his Proclamation to the English People was printed at a press set up in the drawing-room. A frequent visitor to the house was Alexander Pope, who came to stay with his friend “the good Lord Digby”; he is said to have written his Essay on Man in an arbour in the grounds. A Roman pavement discovered hereabouts is now the floor of the castle dairy.

Impressive and captivating as Sherborne is, its most thrilling possession is the ruin on a high knoll between two streams. It was the home of Raleigh in the days before he began the great house. The stone walls are broken, but there are magnificent fragments which thrill us with the thought that they are as Raleigh saw them - a round Norman pillar perfect with its capital and the walls of what appears to have been the chapel, with a lovely broken window on one side and a window complete with four rows of ornament on the other: it has shafts and an inner arch, and is the best part of the walls. There are three doorways, little chambers and corbels, fireplaces and Tudor windows, and great masses of masonry which are none too safe, all approached through a gatehouse with a high lantern tower and a Norman archway. This gateway, which is almost entirely Norman, was the only way into the castle, which was strongly defended by a moat 30 feet deep and by two lakes and marshy land on three sides, a narrow causeway leading to the gate. Just below is a farm, looking as it probably looked in Raleigh’s day; beyond is the abbey tower rising above the roofs; and all round the outer walls of the old castle is the glory of an English park, with nothing to break its silence but the song of birds. The ruins have been excavated in our time by Mr C. E. Bean, and a covered way from the castle down to the low ground has been found.

But there were great men here before Sir Walter Raleigh, and fine places before the castle, for Sherborne School was founded by Aldhelm as the 8th century was breaking. It is thought that Alfred was a scholar here, in a school then new. The Grammar School was spared when the monastery was destroyed by Henry the Eighth, and Edward the Sixth, the boy king who did so much for schools, endowed it. He is not forgotten, for his statue looks down on the boys as they flock into their ancient dining-room.

Many of the old monastic buildings now form part of the school. The Abbot’s Hall is their chapel, and the 15th century Abbott’s Lodging is converted into studies. The walls of the room where the monks received their visitors are covered with books. Perhaps the most charming bit of it all is the 17th century school-house, now the dining-room. Above its square hooded doors and mullioned windows extends a pillared balustrade of exquisite grace, and the Stuart arms over the doorway proclaim its loyalty. The wide courtyard, dominated with the tower of the abbey, dreams in the quiet noontide till the hour strikes from the abbey bells, when doors on all sides are flung open and hosts of boys flock out into the sunshine as Sherborne boys have done for about 1200 years.

We remember a picture over the door of the school chapel of Christ among the lilies, the gift of an Old Boy who painted it and sent it to the school “where he learned to love the holiness of beauty.”

We remember also the noble roll of honour with 59 Sherborne boys who won the DSO, and two who won the Victoria Cross. The VC’s were Charles Hudson and Edward Bamford. On the day Captain Hudson won his VC nearly all the officers of his battalion had been killed or wounded. The enemy had penetrated the line and almost reached our right flank. Hastily collecting some men, the captain charged the enemy, drove them back, and led a party of five up a trench where the Germans were 200 strong. Climbing over the parapet with only two men, he rushed the position although severely wounded, and went on directing the attack until a hundred prisoners and six machine guns were taken and the perilous situation was saved. Captain Bamford’s VC was won at Zeebrugge. It must have seemed that he was leading his marines to inescapable death when, after landing on the Mole, they stormed German batteries in the face of almost insuperable difficulties. Twice he crossed the Mole under heavy fire, establishing a strong position.

Today there are 450 boys sharing the atmosphere and the high tradition of this school, and it was good to find a sister School for Girls, founded by Mr and Mrs Kenelm Digby, with 300 girls on its rolls.

One other bit remaining of the monastery is the 14th century Conduit where the monks used to wash and shave. Finely preserved, it stands just off the lowest, widest, and busiest part of the street, its fine window tracery and the vaulted roof perfect of their kind. No finer architectural group is here than this graceful stone structure against its background of black and white timbered houses, with high roofs, tiny dormer windows, and rising behind, as if to crown a mass of ancient beauty, the slender pinnacles of the abbey tower. A wondrous sight it is, majestic at all times but like a dream on a Spring market day, when piles of oranges, lemons, and rosy apples stand out against the soft brown stone of the Conduit and the sheaves of mimosa, narcissus, anemones, and daffodils form a living and fragrant frame to an unforgettable picture.

Yet the heart of Sherborne is not here, but in its abbey, built in 706 by the wise St Aldhelm, its first bishop. A charming story tells us that King Ina of Wessex persuaded Aldhelm, then Abbot of Malmesbury and an old man, to undertake the hard task of organising the new diocese, where much rebellion and opposition were to be expected; and that the scholar began his new work by putting on the simple habit of a minstrel, winning all hearts by the sweetness of his song.

Aldhelm’s church was a cathedral, and such it remained for 370 years, during which time there were 27 Bishops of Sherborne. Not until 1075 was the seat of the bishopric removed to Old Sarum. In 998 was founded here the monastery of which the cathedral became the abbey church. We may see a built-up doorway and a fragment of wall which were part of St Aldhelm’s Saxon church, there when the Norman building was set up. Inside and out this place is wondrous to behold; it crowns with ancient grandeur the medieval town where we may all forget the stress and strain of life.

The Norman work includes the tower, with magnificent arches as far up as the bells, the finely restored south doorway which has a room above it, and part of the transepts. The two turrets of the Norman porch have each twenty little carved heads and four corner ones, great gargoyles, and parapets with roses in the quatrefoils.

The 13th century saw the building of the lady chapel and Bishop Roger’s Chapel, and in the 15th century this grand old place was decorated and transformed as if a Norman knight had put over his armour an embroidered tunic and a cloak studded with gems. The lower part of the pillars in the arcades was cased in graceful panelling, fine spacious windows took the place of the Norman triforium, and the clerestory and the great west window were opened out. The choir was practically rebuilt; the light and lofty stonework of its arches springs from floor to roof like a graceful tree, and breaks out in the wondrous fan-tracery of the roof, considered by some to be the most perfect example of fan-vaulting in England. It is a miracle of grace. Bishops and abbots of Sherborne look down from windows round the choir. Beneath them, and within the panels of every arch, are wall paintings which carry the eye in a riot of colour to the glories of the roof, where every boss and every panel of tracery glow in rich shades picked out in gold. Completing this brilliant mass of colour the naturally rich brown of the stone is in many places a deep red, attributed to a fire 500 years ago.

There are ten canopied choir stalls covered with carvings whose miserere seats depict quaint figures and scenes in the Middle Ages. Here a schoolmaster is soundly thrashing a boy lying across his knees; there a hen is gleefully hanging a fox; one hunter is drawing his bow while another wrestles with a lion; a grotesque head is set in a framework of vine leaves, and from every elbow-rest peer out weird and fanciful faces. In front of these priceless seats, the work of the 15th century, the modern stalls, the Bishop’s Throne, and the sedilia are worthy of their glorious predecessors. Carved in 1858 from 15th century roof beams, they are beautiful with angels, fruits, and wreaths of flowers.

The fan-vaulting of the nave and transepts is as fine as that of the choir, but the mellow brown of the stone is only enhanced by corbels of angels bearing azure shields and wonderfully painted bosses. A true lover’s knot unites the initials of Henry the Seventh and his queen Elizabeth of York. We see the Tudor rose, the emblems of the Passion, shields, dragons, and other mythical creatures. A rebus illustrates the name of the great Abbot Ramsam who carried out the magnificent 15th century restoration, his device showing a Ram with the letters SAM. Altogether there are 800 of these painted and gilded bosses, some of those in the north transept weighing half a ton.

In this wonderful roof endless waves of lacelike design rise one behind the other like the filmy crests of the on-coming tide, and its insistent beauty attracts the gaze as inevitably as the fathomless blue of an Italian sky. When all this glorious work was finished in 1490 a great fair was held in Sherborne, and Pack Monday Fair has been held on the second Monday in October ever since.

The south transept has a panelled roof of black Irish oak with gilded bosses. This is the chapel of the Digbys, benefactors of the abbey now and for many generations. There is a somewhat overwhelming monument to Lord John Digby, who died in 1698; he is standing between two wives, who are holding a lamp and a burning heart. The wigs of the ladies are piled in tight curls about their heads, and the ornate stiffness of the carving is equalled only by the pompous inscription. A skull and cross bones are the most natural details of the whole erection, and plump cherubs, their faces distorted by grief, guard it on either side.

In an inscription written by the poet Pope to Robert and Mary Digby, both of whom died young, are the lines:

Yet take these tears, MortaIity’s relief,

And till we share your joys forgive our grief.

These little rites, a stone and verse, receive,

Tis all a father, all a friend, can give.

To many it will seem that the most precious corner of this great place is in the chapel dedicated to St Catherine, where Raleigh used to sit. It has a beautiful 16th century memorial to John Leweston and his wife. On the canopied tomb the knight and lady rest in stately dignity, he fully armed with his feet on his helmet. Above the face of the lady her hair is gathered in a tightly-fitting cap beneath a wide-folded headdress. Her brocaded dress closely follows the lines of her figure, and she wears a ruff. But the finest tomb is that of Sir John Horsey, lying by the side of the young son who followed him to the grave in 1564. Both are in armour and are carved by a master, their family crest, the head of a horse, crowning the four corners of their canopied tomb.

Here, with nothing that is spectacular to mark it, is a thrilling spot which must seem sacred to all Englishmen. It is marked by a brass tablet behind the altar, near which lie two stone coffins of kings. They come to us from Saxon England and in these coffins were laid two brothers of King Alfred. This is what the tablet says:

Near this spot were interred the mortal remains of Ethelbad and of Ethelbert his brother, each of whom succeeded to the throne of Ethelwulf their father, King of the West ‘Saxons, and were succeeded in the Kingdom by their youngest brother Alfred the Great.

These coffins have been known for not very many years; Ethelbad’s was found in 1858 and Ethelbert’s in 1925. Ethelbad reigned five years, dying in 860. He helped his father to win a decisive victory over Danish pirates at Ockley in 851, an event to which is attributed the peace of his reign and the popular esteem in which he was held, all England mourning for him. Ethelbert was bequeathed the Kingdom of Kent, but on the death of his brother Ethelbad he became King of Wessex, reigning until 866. During his reign the Danes sacked Winchester, but he drove them off. His reputation was that of a peaceful and noble king.

The first of these kings was found just after the time of John Parsons, who was vicar here more than 52 years. He has a tablet but needs no monument, for it was by his exertions that the restoration of this church was begun and to a great extent completed, in 1851.Here sleeps a hero of the Indian Mutiny, Andrew Cathcart Bogle, VC. He died at Sherborne House after three years of patient suffering, having won his VC for conspicuous gallantry in leading the way into a house strongly occupied by the enemy, from which a heavy fire harassed the advance of his regiment. The Dorset soldiers who fell in the Great War are remembered by two finely carved oak screens, and the restoration of the base of the 14th century stone screen is the memorial the Freemasons offered to their fallen brethren.

We do not know where Cardinal Wolsey used to sit when he worshipped here while he was tutor to the Marquis of Dorset’s sons, but his monument, a far from silent one, is the huge tenor bell, Great Tom, which he gave to the abbey in his spacious days of prosperity. He brought seven enormous bells to England from the Continent, and Great Tom was the smallest of the seven. It weighs two and a quarter tons and needs six men to ring it, and its inscription reads:

By Wolsey’s gift I measure time for all,

To mirth, to grief, to Church, I serve to call.

For many years Great Tom hung silent in his chamber, but the bell has now been recast, and just before we called had been brought home from the foundry welcomed by all the town, a hundred boys of the School drawing it triumphantly back to the abbey to rejoin its seven companions. The Fire Bell, rung only for great conflagrations, bears this delightful rhyming version of the saying that God helps those who help themselves:

Lord, quench this furious flame:

Arise, run, help put out the same.

Among its big brothers hangs the small sanctus bell which used to ring before the Reformation. Near the porch door stands an old clock made by William Monk in 1740; he was paid £25 for it.

In the south choir aisle, near a fine old table and the old canopy of a pulpit, lies on his tomb the figure of Abbot Lawrence of 1246, and by the still beautiful lines of the drapery on the tomb we can tell what must have been the dignity of his figure before folly defaced his features.

The old glass of the abbey is all in two windows of St Catherine’s Chapel (where Raleigh used to sit). Here some lovely fragments of 15th and 16th century work have been grouped, and stand out vividly on a clear background. The glass was taken from the choir in 1856 and stowed away in the Muniment Room, where it was almost forgotten until 1923, when it was set up again to the memory of the fine old craftsmen of the Middle Ages. There are the quaintest little figures in the medieval dress of saints and prophets, and many coats-of-arms. In the chapel which is now the Children’s Corner are some tiny medallions of greenish glass, yellowed by age, showing the Madonna and an angel’s head with outstretched wings. The south window of the Digby Chapel (designed by A. W. Pugin) illustrates the Te Deum, and in Abbot Ramsam’s great west window are Old Testament kings, prophets, and patriarchs. The rich effect of the whole interior is intensified by the colours of the Dorset regiment, which have been carried in engagements in various parts of the world from 1829.

A 13th century archway leads to the lady chapel, which has been brought back to life in our own time, having long been cut off from the abbey and used as part of the school. By the generosity of the Digbys it has been returned to the church. With its fine 13th century vaulting, archways, and capitals, it is a fitting continuation of the lovely choir. A new sanctuary has been added, and five beautiful screens. It is now a charming place, an east end worthy of this great shrine.

The abbey was given to Sir John Horsey after the Dissolution, and the people of Sherborne bought it from him for £230 and made it their parish church, destroying the church of All Hallows next door, which had been the cause of many quarrels between them and the monks because it was not licensed for baptisms. These quarrels led to the disastrous burning of the abbey. Another record of these unworthy disputes is a small doorway now bricked up at the west end; it was the only door by which the townsfolk could enter, and was narrowed by the monks as if to mark their own superiority.

Across the space in front of the abbey is a rare old building everybody loves to see, the Hospital of St John. The abbey stands guarded by two endowments of pious benefactors, the school and the hospital. Abbey, school, almshouse, and castle - all were the work of churchmen, those princes of the church who laid the foundation of England as warriors, lawyers, statesmen, and scholars. This charity, governed by 20 brethren known as Masters of St John’s House, provides a home for twelve poor men and four poor women. The charming group of brown stone houses has been made more comfortable since the 15th century, but its medieval grace and character have been preserved. In the cloister sit the old men in black suits with shining buttons and low felt hats, the snow white pigeons of the abbey fluttering and strutting about their feet. The sunny sitting-room of the old ladies was gay with flowers when we called, and in their comfortable chairs we found them chatting and smiling, wearing their white lace caps. The original oak door, hinged in the middle and still with its early iron bolts and fittings, leads into a dining-hall with Jacobean chairs, tables, and stools. On the high dresser is ranged some fine old pewter.

By a 15th century archway, with a screen of the same time hewn from solid oak, we come into the tiny chapel where the men sit below and the women look down from a gallery above. There are two precious things here. One is a 15th century triptych, with three panels illustrating the Miracles: the healing of the widow’s son, the raising of Lazarus, and the casting out of a devil from a dumb man. Strangely interesting is the early artist’s conception of the little scaly demon coming from the man’s mouth, wearing a mitre. Miniature pictures in the corners show two more miracles. There is little doubt that this was given as an altar-piece by the founder of St John’s, and we love to think that for more than 500 years the old folk have found new strength and comfort in this. The triptych was painted on oak by an unknown artist. Its colours are fresh and brilliant; the 15th century costumes, shoes, and headdresses are of extraordinary interest, and the lifelike painting of the many faces is startling. On the outer side of the doors are the figures of four Apostles.

The other rare possession in the chapel is the painted glass. The fragments of 15th century glass in the south window have been arranged to form three charming figures in glorious colour. The Madonna in the centre is considered to be one of the finest examples of medieval glass in the county. The two St Johns are on either side. The restoration (by Mr Horace Wilkinson) is an exquisite specimen of work, each new piece having been marked by a diamond, so that the old and new work can be compared in this lovely harmony.

One great treasure Sherborne has given to England’s famous manuscript collections, the Sherborne Missal, an order of Church service written some time between 1396 and 1407 by John Whas, and illustrated by his brother monk John Siferwis. It is one of the finest examples of English illumination, and it must have been towards the end of these eleven years that John the writer said:

John was the monk took pains this book to write,

Such early rising leaves him lean and white.

The narrow winding streets of this old town, with their fine houses and gateways, their oriel windows and irregular gables, charm us at every turn. It is little wonder that Sir Walter Raleigh, a broken prisoner in the Tower, who had seen the marvels of the old world and the new, dreamed with longing of his pleasant home by the little river Yeo, and prayed that he might lay his weary body within its quiet shadows.

Flickr.