It is a magnificent building both inside and out but I have to say that they really need to declutter the interior, the interior is full of ill thought rubbish throughout. I'd also throw out the grumpy old vociferous git in the south aisle who added exactly nothing to the pleasure of the visit. Had it not been the House of God it could have turned nasty!

THE MINSTER. Cuthburga, sister of King Ina, founded a nunnery at Wimborne about 705 of which in the end she became abbess. In the late C10 the Danes destroyed the nunnery. Edward the Confessor revived religious life by creating a college of secular canons. The college was called a deanery under Henry III. Edward II in 1318 declared the church a free chapel, exempt from ordinary ecclesiastical jurisdiction. It was dissolved in 1537.

Of the collegiate buildings nothing is preserved, but the church is there in toto - 186 ft long internally. C19 restoration took place in 1857 (T. H. Wyatt) and 1891 (Pearson).

Wimborne Minster, as nowadays one drives round and round it, is imposing, but it is not beautiful. What is it that spoils it? The spotty brown and grey stone in the first place, the competition of crossing tower and W tower in the second, too similar in height, i.e. neither dominating, and too similar in bulk, and the uncouth top of the crossing tower in the third. But imposing the crossing tower is - a mighty tower. And that is where an inspection of the building ought to start.

The CROSSING TOWER, specially spotty in its stonework, has a first stage of windows, two round-headed ones to each side with a blank pointed arch between. The windows are double-shafted. The capitals of the shafts have trumpet and crocket and stiff-leaf forms. So we are late in the C12 here. On the W side the nave roof cuts into that stage. The stage above has intersecting arches, and it is interesting to note that pointed lancet windows fit into the intersections. It was one of the theories of the late C18 and early C19 concerning the origin of the Gothic style that it had come about naturally by means of intersecting arches. Nowadays we know that styles do not come about in that way. All stages together have giant angle shafts with shaft-rings. The tower had a Perp stone spire, and this collapsed in 1600. The decidedly clumsy corbelled-out top with its obelisk pinnacles dates from shortly after.

The TRANSEPTS are Norman too, though the N transept only as far N as the round stair-turret. The extension can be dated to c.1260-70 from the correct, if over-restored, geometrical window tracery. The N window has four lights, two quatrefoiled circles and a larger sexfoiled one at the top. The E and W windows are of two lights only, also with a foiled circle. The S transept is different, first because the SACRISTY with the LIBRARY over, an addition of c.1350, hides its l side, secondly because the S window is of five stepped cusped lancet lights under one arch - i.e. a late C13 motif. The Norman masonry is particularly telling in the bare W wall.

We continue first to the E, then to the W. The EAST END shows the choir projecting by only one shallow bay. The E has three separate uncusped stepped lancets, with sexfoils and quatrefoils in plate tracery. This may be called c.1250. The N choir aisle starts from the transept with one small Norman doorway, earlier obviously than the crossing tower, but, according to the RCHM, re-set. Its tympanum has a concave underside. The windows, with cusped Y-tracery, are C19 (RCHM). The same is said of the stepped lancets in the choir aisle.

So to the NAVE. It is the same both sides, except for the N porch. The aisle windows are first from the E of two lights with bar tracery, i.e. later C13, then, further W, they have cusped Y-tracery, i.e. earliest C14. The clerestory is the first Perp feature we meet. Three lights, a straight top and elementary panel tracery between lights and top.

The NORTH PORCH dates from the late C13 but has a C15 upper storey. The lower storey is rib-vaulted in two bays, the ribs with fillets, the bosses with naturalistic foliage. The wall-shafts are of Purbeck marble. The entrance has continuous mouldings including a fillet, the doorway two continuous chamfers.

The WEST TOWER is forbidding, where the crossing tower is loquacious. It was built from 1448 to 1464, and is 87 ft high. As W doorway and W window are Victorian, it is almost sheer to almost the top. It has polygonal clasping buttresses (cf. Bradford Abbas). The bell-openings are two each side, of two lights with a transom.

So much for the outside; now the INTERIOR. Here again we must begin at the CROSSING, and, as might be expected, because it takes some time to build a crossing tower, the four arches on which it stands are in fact more than a generation older than the rest. In fact the whole crossing as such may go back to the Anglo-Saxon predecessor of the present building. The argument is the extruded outer angles of the crossing piers, the motif also found at Sherborne and e.g. at Stow in Lincolnshire. It means that the crossing was not strictly a crossing of identical chancel, transept, and nave width, but slightly wider in both directions - an Anglo-Saxon illogicality. But even leaving this out of consideration the Norman crossing can hardly be later than, say, 1140. Two shafts rise to the round, single-step arches, depressed W and E, stilted N and S. In addition there are subsidiary single shafts. The capitals have comparatively large and few scallops. The next stage inside has a wall-passage with Purbeck shafts arranged in groups of four lights with round arches under one pointed relieving arch. The top stage inside, corresponding to the lower outside, has shafted windows.

The crossing campaign extended into nave and choir, as we shall soon see. But first the TRANSEPTS. The arch from the N transept into the choir aisle is Dec. But one impost of the Norman arch remains, and next to it, to the N, a perfect Norman altar recess, very simple and totally undramatic. In the W wall is a small Norman doorway. It leads to the tower staircase, which continues high up as a corridor on corbelled courses. The C13 windows are shafted. The S transept has the arch to the choir aisle like the N one, but the Norman recess has been spoilt to become a subsidiary entrance to the aisle. The lancet to its S was blocked when the sacristy and library were built. In the S wall a PISCINA with trefoiled head, the moulding all studded with dogtooth.

There is good reason to continue with the NAVE* rather than the choir: for it is in the nave that the Norman story continues. As a matter of fact Wimborne inside is largely a Norman building, which one would not guess externally. The Norman nave arcades begin from the crossing with a very narrow bay. That, as the scallops and fishscales of the E corbels show, belongs to the crossing, although the single-step arch is pointed. This first bay had to be built to secure the job of carrying up the tower. It acted as W buttresses. The entrances from the transepts to the aisles on the other hand are not now Norman. They have C13 Purbeck shafts with Perp capitals but C13 arches. High up in the nave one can see the former roof-line and in the gable a small Norman window. The next three bays of the arcade start after a short bit of solid wall. They are Late Norman. Round piers, many scalloped capitals, square abaci with nicked corners, higher pointed arches with zigzag, also at r. angles to the wall. On the apexes of the arches human and monster heads. Above, a course of small, shallow zigzag serving to mark the sill of the Norman clerestory windows. Here again bay one is slightly difierent from bays two to four. Above all this is the Perp clerestory. The W respond of this Norman arcade stretch is followed by some wall representing the Norman W wall. An extension took place early in the C14. It was of two bays, but the C15 tower cut into the second of them. The NE impost has ballflower. The piers are octagonal, the arches double-chamfered. The tower arch is very high and has large-scale Perp roll and wave mouldings. In the tower a tierceron-star vault.

The CHOIR starts with a Norman bay with responds like those of the crossing but capitals with small busy decoration. The arches are pointed and single-stepped like those of the nave E bay. Against the wall of the crossing, just as on the W wall, the former roof-line is marked, and in the gable is a small Norman window. The next bay is of the time of the E end: it has three orders of shafts and a triple-chamfered arch. The upper windows are Victorian. Steps lead up now to the high choir. The boundary is marked by giant triple shafts with thick leaf capitals. The E bay towards the choir aisles has Purbeek shafts, including a triple one and beautifully fine mouldings with fillets, again c.1250. Outstandingly good hood mould stops, especially Moses. But surely they must be re-used, as they represent the style of c.1200. Two clerestory windows of c.1250. The three stepped lancets of the E wall are rather wilfully expressed inside by a stringcourse which follows the arches but is blown up then to run round the foiled circles too. Against the S wall of the chancel is a delightful Dec group of PISCINA and SEDILIA, with crocketed ogee gables; but the exuberant finials are Victorian.

That leaves the vaulted separate rooms - the sacristy and the crypt. The SACRISTY has an octopartite rib-vault, the ribs finely moulded, including the Dec sunk-quadrant moulding. The CHAINED LIBRARY above has no architecturally interesting features. The CRYPT is Dec too, but of two dates. The (more attractive) W bay with responds and continuous mouldings with fillets may be of c.1350, for the E part the RCHM suggests c.1340. W bay as well as E bay are of three bays’ width. The two parts are divided by three cusped arches.

FURNISHINGS. From E to W, and N before S.

CHOIR. The STALLS date from 1610. They are medieval in type but have the familiar blank arches on their fronts and foliage on the arms. — The same is true of the READING DESKS. — STAINED GLASS. The middle E window has a Tree of Jesse, Flemish, early C16, brought in, but alas much damaged. — MONUMENTS. King Ethelred, brass demi-figure, 141/2 in. long. Made c.1440. - John Beaufort Duke of Somerset d. 1444. Purbeck tomb-chest with cusped quatrefoils. On it two alabaster effigies. — Marchioness of Exeter d. 1557 — yet the same tomb-chest still and not a touch of the Renaissance.

NORTH CHOIR AISLE. STAINED GLASS. The heraldic window is by Willement, 1838. - MONUMENTS. Defaced late C13 Knight. - Sir Edmund Uvedale d. 1606. Standing alabaster monument. He is lying on his side, his pose more relaxed than usual. Two colunms, two obelisks, strapwork and ribbonwork. - Above a funeral HELM.

SOUTH CHOIR AISLE. STAINED GLASS. The heraldic window is by Willement, 1838. - MONUMENTS. William Ettricke d. 1716. Large tablet without figures. - Anthony Etricke, 1693. Black shrine with painted shields.

CROSSING. The majestic stone PULPIT is of 1868; the carving was done by Earp. - The equally majestic brass LECTERN of the eagle type is dated 1623.

NORTH TRANSEPT. The WALL PAINTING in the Norman recess is illegible now. It is of three layers, C13, C14, C15. The two later ones are Crucifixions.

SOUTH TRANSEPT. ORGAN. By J. W. Walker & Sons, 1965. The sound comes only partly through the pipes. Above there is a display of gilded trumpets sticking out, and they convey the sound too — a delightful idea. - A number of TABLETS, the best John Moyle, 1719. There are altogether at Wimborne quite a number of good tablets of the late C17 and early C18. It would take up too much space to describe them all. The best will just be listed as an appeal to examine and compare them.

NORTH AISLE. STAINED GLASS. The second window from the E (1859) must be by Gibbs. - MONUMENT. Thomas Hanham d. 1650. Two kneeling figures facing one another across a prayer-desk. This is a motif of Elizabethan and Jacobean funerary sculpture, but the pediment and the sparse foliage are post-Jacobean. - TABLETS. Harry Constantine d. 1712. - Thomas Cox d. 1730.

SOUTH AISLE. TABLETS. Bartholomew Lane D. 1679. - William Fitch ‘did in his lifetime cause this marble to be erected’ - 1705. - Warham family, 1746. - George Bethell d. 1782. Trophy at the top, but now also an Adamish oval patera at the foot.

TOWER. FONT. Black Purbeck marble, octagonal, with two blank pointed-trefoiled arches each side. - CLOCK. The case of v.1740. - STAINED GLASS. The W window is by Heaton & Butler; date of death commemorated I852.

PLATE. Cup and Cover, 1604; Cover, 1634; two Cups, 1638; Flagon, 1681.

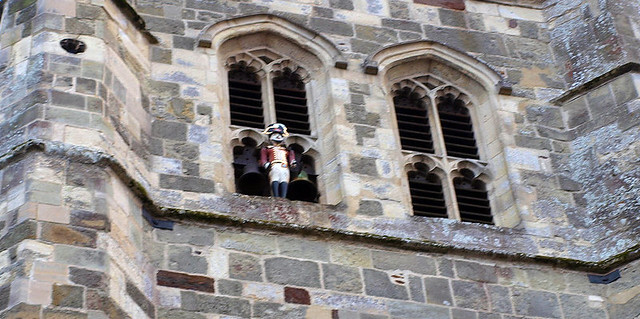

Outside the building against the bell-openings to the N is the QUARTER JACK, early C19. - In front of the S side of the tower a monumental free-standing SUNDIAL on a high square base. It is dated 1676.

* A small piece of mosaic pavement was found under the nave in 1961 (R. Peers).

WIMBORNE. For centuries it has been like a magnet to the traveller in the meadows where the road crosses the River Stour by an ancient bridge. It has the narrow winding streets of the old medieval town, but they bring us to its great glory set in a pleasant green space just off the Square. Wimborne has little but its Minster, but what more does it need than this noble piece of our ancient land, a splendour to look at, an inspiration to walk in, a veritable monument of English history?

Alfred was here as a boy, and we must think of him as standing on this very spot with a prayer in his heart that he might be a true King of England, for here he stood by his brother’s grave, with the shadows gathering about his country, and he, a boy of twenty, King.

How far down the mists of time this minster takes us we do not know, but the thread that runs through the life of our island here reaches back to the days of Rome, for a Roman pavement lies under the minster floor. Here there was a Saxon nunnery 1200 years ago, founded by St Cuthberga with her sister Quinberga. They had a little nephew growing up whose name was Aldhelm, and whose fame was to spread wide as the founder of abbeys that still remain with us at Sherborne and Malmesbury. They were the sisters of King Ina, who ruled the West Saxons for more than a generation, and their sacred place was of such repute that when Ethelred fell in battle it was here that they laid him. The fame of Cuthberga’s convent spread far and wide, and Wimborne became the Girton of its day, a training college sending out women who played their part in evangelising Europe. Cuthberga was abbess here for 20 years, and we must believe that here she lies in an unknown grave. No other church in England bears her name.

Edward the Confessor gave new life to the old minster, and when the Conqueror came his builders transformed this shrine of a Saxon king. Centuries passed by, and Margaret Beaufort, the mother of our Tudor dynasty, founded a chantry and endowed a priest to teach grammar to all comers, and in another 100 years Queen Elizabeth founded the Grammar School as part of these great buildings that had developed as we see them during three centuries, from the Normans about 1120 to our master builders of the 15th century. After Elizabeth the tragic shadow of the Civil War passed over Wimborne, and in the exciting days of Charles the Second the miserable Duke of Monmouth was captured in a ditch not far away. Then Wimborne went to sleep again, and little has happened except that the town itself has lost some of its beauty while the old minster lives on as if it were all the world, unspoiled by time and still with the power to lift our thoughts far from these troubled days.

The minster is a noble spectacle, with its two great towers of almost equal size and height, the 15th century bell tower rising 95 feet from the street and the central Norman tower which has lost its spire and rises 84 feet. The central tower is the oldest visible part of the minster, rising to four stages of massive Norman piers and plain arches, the east and west wider than the north and south to give a fuller view of the altar. The three lower stages are open from the inside, and we have a thrilling impression of strength and beauty as we stand looking up at the great stones and the cunning workmanship of 800 years. A gallery built in the thickness of the walls runs round the second stage, and grotesque heads peer from between its arches. An almost hidden staircase in one corner leads to the clerestory, which lights the lantern and also has a passage in its walls. Inside and out the tower is decorated with fine arcading, having an interesting and varied series of piers and capitals. A corbel table 700 years old is the limit of the early work; one corbel shows a man devouring a bone.

There is more Norman work in a tiny stair turret of the north transept walls, in an altar recess in the same transept, and in the bays of the nave and chancel near the tower. We see in the nave how century by century the builders left the best of the early work, adding to it bit by bit in beautiful harmony, inspired by the spirit of their time.

Westward beyond the fourth pillar of the nave arcade the Norman ends; this was the western wall of the Norman church. Now the work is 14th century, when aisles were added with graceful east windows. From the 14th century also comes the north porch, with its vaulted roof and bosses; it has stone seats and a small priest’s room over it. Above the row of small Norman windows in the nave the 15th century clerestory was added when the western tower was built. In this tower is the ringing-loft above the vaulted roof, and outside one of its windows stands the famous wooden Quarter Jack, who with queer contortions strikes the quarters with a hammer. He has delighted Wimborne children since Charles Stuart was king, but he has changed much with the flight of the time he tells. Once sedately clothed as a parson, he now wears the dress of a British Grenadier of the days of Napoleon. There are few more popular figures in Wimborne than this bit of painted wood.

Older than Quarter Jack is the Orrery in a wall of the tower, still working after 600 years and more, for it was made in 1325 by Peter Lightfoot, the Glastonbury monk who made two or three other astronomical clocks we have seen in the West Country. A quaint thing to look at, this old clock is notable as a landmark of knowledge, for it was going 200 years before we knew that the sun does not revolve round a fixed earth, and we see on a blue background representing the sky the sun, moon, and stars all revolving round our planet, the sun completing its circuit in 24 hours and the moon in a lunar month revolving on its axis, shining gilt at full moon, changing gradually to dark. The clock is crowned with the figures of two winged and trumpeting angels.

Wimborne folk, with Jack and their Orrery, are rightly proud of their fine peal of bells; the tenor, weighing a ton and a half, has been ringing out since Richard the Second was pleading for a little grave to lie in, a little, little grave, an obscure grave. For five or six centuries this bell has called Wimborne to prayer.

We come inside the massive minster and are not disappointed. Something in this stately interior draws all eyes; it is the east end, rising impressively by 14 steps from the floor of the central tower. The ascent is made in two stages, halfway to the choir and on to the sanctuary, so giving the eastern interior a grand appearance. The whole minster is divided as a cathedral, with nave, chancel, choir, aisles, transepts, and three porches, and the length from east to west is 60 yards. In the 13th century the Norman chancel was extended by 30 feet and the builders gave their new wall a set of three lancets rarely surpassed in beauty of stonework, the central lancet enriched with the old glass in the church. The sedilia and the piscina have richly decorated canopies, and there are 16 canopied stalls, all carved.

Among all the splendour of the tombs in this fine place it may be that a brass in the pavement will move the traveller most of all. It covered the grave of King Ethelred and has a medieval portrait of the king engraved on it, with an inscription in Latin which says:

In this place rests the body of St Ethelred, King of the West Saxons, Martyr, who in the year of Our Lord 873 on the 23rd day of April fell by the hand of the pagan Danes.

Though the brass does not go back to Ethelred’s day, it is believed that it long rested over his grave. This stirring memorial has now been set in the chancel floor at the point where the high altar of the old church stood. It is recorded that the skeleton of a tall man was found here some years ago, but it cannot be said whether the remains were those of Ethelred. In any case it is a historic stone, and there is a mistake on it which should be corrected, for the date 873 should be 871.

Somewhere in this sacred spot of earth about us Ethelred lies. He fought nine battles hereabouts in the first year of his reign against the raiding Danes. It was in these battles that his young brother Alfred found his mettle, and it was the fall of Ethelred that made Alfred king. His first act as king was to stand by his brother’s grave where we stand now. He was 20, and his heroic spirit was stirred by the attacks of the Danes. He set up a palace two miles away, at Kingston Lacy, and enjoyed some years of peace, dreaming of a British fleet and building it, and at last he beat the Danes at Wareham and signed a treaty of peace with them. They came back in spite of treaties and desolated Wimborne, burning down the minster, and the young king, humiliated and betrayed, hid in the marshes of Athelney in Somerset, where every schoolboy knows that a housewife rebuked him for burning her cakes. Alfred was thinking of ships, and his fleet grew to 100 vessels, and in the end he kept down piracy, gave England peace, and made himself beloved throughout the land.

The noblest tomb in the minster is that on which lie John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, and Margaret Beauchamp, his wife. They are on the north of the choir, graceful figures in alabaster. They were the father and mother of that Margaret Beaufort who was the mother of the Tudor Dynasty, and lies with her son in the noblest chapel in London which he built for himself, facing Parliament. The duke lies fully armed, with his gauntlet in his left hand, and his bare right hand lovingly holds his wife’s. She has rings on her fingers and her bodice is fastened by a jewel, her veil being held in by a simple coronet and falling about her shoulders. A queer creature at her feet keeps company with a lion at his feet. The exquisite flowing lines of her robe fall over her feet, and above them hangs a rare helmet 500 years old; we were told that it weighs over 14 pounds.

Across the choir from this fine tomb is a tomb with no figure, but with a broken inscription which tells us that it is in memory of Gertrude, the unhappy wife of Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Devon. She sleeps alone, for her husband, lord of his proud Devon house, whose grandfather had helped to set Margaret Beaufort’s son on the throne at Bosworth Field, and who bravely stood with Henry the Eighth on the Field of the Cloth of Gold, displeased that proud king, fell from his high estate as the most powerful man in the west of England, and was beheaded.

The minster’s most magnificent tomb is the Elizabethan monument of Sir Edmund Uvedale, setup by his widow as “a doleful duty” three years after the death of the queen. It is the work of an Italian master hand, with a background of alabaster richly decorated in coloured scrolls, fruits, and other devices, and rising nearly to the roof of the aisle. On the tomb the knight reclines, and is slightly rising as if waking from sleep. It is indeed a sermon in stone. The life-like expression of the stern yet tender face is one of expectancy and earnest hope, every line speaking of a man who walked with God.

Near this tomb in all its splendour is the broken figure of a crusader, a poor battered stone thing believed to be part of the statue of Sir Piers Fitzherbert. Somewhere under the floor here lie two sisters of whom we should like to know more but of whom we know nothing except that one married an Excise Officer in Wimborne, that one died in 1759 and the other a year later, and that they were the daughters of Daniel Defoe. There is a 17th century wall monument of white marble on which Thomas Hanham and his wife are kneeling at a desk, dressed as in Stuart days, and from the end of Stuart days comes the tomb that all the curious look for here, that of the Man in the Wall. Here lies Anthony Ettrick, Recorder of Poole, a very eccentric fellow who annoyed the people of Wimborne and resolved to annoy them further by setting them a riddle when he died. He declared he would lie neither in nor out of the minster, and had his own coffin made, an oak one in a black slate case engraved with the date 1691. Fate was kinder to him, and he lived 12 years longer than that, and the date on the slate has been altered to 1703 in brilliant painted figures which remain to this day. His queer tomb gleams with painted shields and his coffin is put in a niche in the wall, so that legend has it that his vow was kept by putting him neither underground nor overground, neither in nor out.

Ettrick is interesting for something else, for he was the magistrate to whom they brought the Duke of Monmouth when they captured him half starved in the ditch, and he it was who put the son of Charles the Second into a prison cell. Two tributes on the minster walls are of unusual interest, one to a sexton who looked after the minster for 52 years (George Yeatman), the other to a son of the Bankes family who went out from Corfe Castle as a Cornet in the 7th Hussars and won the Victoria Cross in the Indian Mutiny, falling without knowing of the honour he had brought to his house. He was William George Hawtrey Bankes.

The windows of the minster are all modern except for the east window’s 15th century Tree of Jesse. The figure of Jesse himself is missing in it, and the lowest figure is David, who is playing the harp. The primitive design stands out clearly in the blue sky, and the Madonna crowning the picture holds the Child surrounded by a golden halo. The glass was brought to Wimborne from a Belgian convent. Two fine windows have settings of the two great Songs of Praise, the Magnificat and the Nunc Dimittis; in them Elizabeth is greeting the Madonna and the aged Simeon is receiving the Child in the Temple. A window of four lights near this in the north transept has great beauty and much historical interest; it is crowned by Christ in Glory, and in the main lights are four historic figures of Wessex, with small panels of scenes from their lives. Dunstan holding a harp is rebuking King Edgar for his treatment of Editha, and the small panel shows him as archbishop. Edward the martyr is giving alms and is also shown receiving his mortal wound as he takes the cup from his treacherous stepmother. Richard of Chichester is working on his brother’s farm as a youth and consecrated as a bishop, and the fourth figure is of St Sidwell, a British lady of high rank in the 8th century; we see her life as a recluse, and afterwards her martyrdom.

What is thought by many to be the best modern window here is one by the Powell workshops in memory of a beloved doctor. It has pictures of the healing and restoration of the sick, with musical angels all round. In the centre is Our Lord surrounded by the suffering, the lame, and the blind, and below are Luke the physician, Christopher carrying a child, and Isaiah, St John, and the prophet Ezekiel symbolise the teaching of the New and Old Testaments, above all being Christ on a throne, from under which flow the waters of healing. In the great west window are the Twelve Apostles.

The fine 19th century pulpit has a central recess filled with lovely detail showing Our Lord delivering the Sermon on the Mount, the Disciples grouped about him and Evangelists in small niches; the book-rest is borne by the Archangel Gabriel. The lectern is valuable for being one of only about 50 brass eagle lecterns surviving from olden days, and interesting because the eagle has eyes of mother-of-pearl.

One of the quaintest corbels we have come upon in any church finishes the arch near the Beaufort tomb. It shows Moses holding the Tables of the Law. We must think that the artist had a keen interest in hairdressing and allowed his fancy to stray on fantastic lines, for the patriarch’s long beard reaches to his waist and is tightly plaited, as schoolgirls used to wear their locks before they were all cut off. A long walrus-like moustache is caught into the plait halfway down, and the hair is smoothly parted in the middle and arranged in two horn-like structures above the forehead.

The crypt below and the library above are both much visited places. The crypt, fitted up as a chapel, has a vaulted roof resting on pillars and is divided into three aisles. The library is up a winding stairway from the vestry; we climbed it to find one of the rarest intellectual corners in England. It has one of the biggest chained libraries in the country, and we may call it the pioneer of free libraries, for 300 years before municipal libraries were dreamed of a worthy minister of Wimborne, William Stone, gave his own library to this place for the free use of Wimborne for ever. Every book was secured by a chain and padlock, and the old chains remain, though the rods are new. There are more than 200 volumes, the oldest of all a vellum manuscript in Latin with illuminated initials written about 600 years ago, in 1343.

A strange story is told of this remarkable little room. In it is a fine copy of the first edition of Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World. At some time a hole was burnt through 104 pages of the book, and every one of these pages has been neatly repaired by a piece of paper stuck over the hole with the text reproduced on each side. The story is told that the poet Matthew Prior fell asleep over the book as he was reading it and that his candle burnt through its pages. We are asked to believe that he was so full of remorse that he repaired the pages himself, but the truth of the tradition is as doubtful as the brass tablet in the west tower which claims Prior as a native of Wimborne; he was actually born in Westminster. Yet the memory of the repairer of this book will live as long as the book exists, thanks to the perfect patchwork of the pages. It has been rebound and completed, duplicate pages from another copy of the same edition having replaced some which were missing.

This rare little room is kept as a small museum. Among the ancient Bibles here is the edition of 1595 known as the Breeches Bible because of the verse in Genesis which reads that “they sewed figge-tree leaves together and made themselves breeches.” On one shelf is a fascinating collection of early church music worth £1000, some of it having been photographed for the British Museum. Much of it is in manuscript, and as we tenderly turn the yellow pages, where queer diamond-headed notes move in stately measure, imagination seems to hear an echo of Gregorian chants rising from the choir below. On a fragment of a Saxon cross here is a crude carving of Our Lord. There is a tiny pewter vessel used for anointing with holy oil; an almsbox for silver only, with so small a slit that no copper coin could pass through it; and two chests full of deeds and charters relating to the minster, some from the 13th century. The oldest churchwarden accounts in England are hidden away here; one on parchment is dated 1399.

The minster has several ancient chests, but the oldest of all, the oldest thing in the building, is a chest hewn from a solid trunk of oak, massive and primitive beyond description. Though six and a half feet long, the inner cavity is only 22 inches long, 9 wide, and 6 deep. It is almost certain that this was the strong box of the Saxon nunnery, in which relics and other treasures were preserved 1100 years ago. Sometime in the Middle Ages six great locks were added, parts of which remain. In the 18th century a number of documents in the chest were examined and some were found dating back to 1200. Another old chest contains title deeds of charity lands for which six trustees are responsible. It has six locks and six keys, and can only be opened when all six holders of the keys are present.

The peace memorial to the men of Wimborne who did not come back is a graceful cross in the churchyard by the north door. By the south door is a huge sundial with three faces. Two inscriptions near one of these doors remind us that Dickens took two of his names for Pickwick Papers from stones hereabout, Wardle and Snodgrass.

The great minster has a little friend which has kept it company through all the ages, the chapel of the almshouses at the foot of St Margaret’s Hill. They are a group of charming cottages endowed by William Stone, who gave the library to the minster. A charming picture in their gardens, the cottages are gathered about the tiny chapel, which was part of a leper’s hospital in the 13th century, and is now primitive in the extreme, with bare walls, a little window, a holy water stoup, fading wall paintings, and one or two seats, a miniature House of God. Simplicity itself is it, in contrast with the spacious and stately minster, yet these two neighbours, rich and poor, have been consecrated through the centuries by the faithful ministry of holy men and the devoted worship of Christian souls.

Here also throughout the centuries the minster has had the grammar school as its companion, and indeed the governors of the school are the governors of the church, for in them was vested long ago “all spiritual jurisdiction” until then possessed by the college. Founded by Margaret Beaufort, the school was dissolved by the boy king Edward, and set up again by Queen Elizabeth. It has scholarships for singing in the choir, and has a reputation given it by Thomas Hardy for “drawing up brains like rhubarb under a ninepenny pan.” The school is housed in a dainty 19th century copy of a Tudor building, and has a great window in the central gable, set between two octagonal turrets crowned with pavilion domes.

With so much that is old and so much that is new, Wimborne reminds the traveller of what we often see in old towns, for behind the modern front so often unattractive is many a lovely peep of paradise, with a little river flowing slowly by.

No comments:

Post a Comment