ST PETER AND ST PAUL. The church is not as impressive as its size would make one expect. Externally it is too varied, and also visually too little connected with the flow of the streets around, and internally it is too curious and unexpected to rouse at once aesthetic reactions - at least to the building as a whole. The curious and, for a while after entering, decidedly baffling fact is that Wisbech church has two naves and two aisles. That is the apt description rather than to say one nave and inner and outer N aisles. The exterior is dominated by a bold tower placed over the N porch ; and in that also irregularities appear which at first prevent an understanding and an appreciation of the church. To understand its history one has to start inside and leave the exterior for later. Inside, the earliest and, after all the later alterations, a somewhat incongruous-looking element is the late C12 N arcade. It is of five bays and has piers with an oddly alternating rhythm of circular and circular with four closely attached shafts in the diagonals. The rhythm is: B (respond)-A-B-B-A-B. The capitals are scalloped, but there is also waterleaf and even in one place something like stiff-leaf. The arches are round and single-stepped. That at the E end is decorated by zigzag. In the spandrels of some of the arches are motifs such as a sunk circle or quatrefoil. It all looks a very reactionary carrying-on of the Norman style into the period of the Earliest Gothic. At the W end the C12-C13 church had a tower. Of this the thicker N and S walls bear witness, with arches opening into former embracing aisles. These arches are pointed and double-chamfered, although even they still use scalloped capitals. Of the Norman chancel nothing can be said. In the first half of the C13 a S chancel chapel was added to it, but of that there is no more proof than one respond with a rich and mature stiff-leaf capital (unless this is re-used from somewhere else).

The next period of building activity is still much in evidence. It is the Dec style of the C14. It was during that time that the church grew to its present size. The most evident witness is the W window of the S nave,* large, of five lights, and with ingeniously devised flowing tracery, the W and the N doorways, the latter now hidden by the tower, and the S porch as a whole. In addition it can be recognized that the whole N chancel was rebuilt. The S wall was kept as it then existed, but the N wall was quite naively pushed out to the N, without bothering about the odd splay which that would give to the last bay of the N arcade. The splayed arch has the same profile as the chancel arch. The N windows also are Dec. The S side opens into the S chancel into which the former S chapel found itself now converted. Its present windows are Perp, but the arcade has typical quatrefoil piers and double-chamfered arches. The same quatrefoil piers and arches also mark the arcade between the S chancel and the S aisle. The clerestory here is partly original. Over the N aisle it is Perp. The S porch is two-storeyed and has a typical outer doorway of the C14. The N doorway to the church was, however, the main entrance from the town, and this must also be C14, though probably a little later. It has nobbly foliage in the innermost order of voussoirs, and divers animals and monsters in the outer order. The hood-mould is carried on good head-corbels. Next to this doorway inside a tall blocked C14 window. This is additional evidence of the date of the N aisle which has otherwise all windows Perp.

The main Perp contribution to the church interior is the somewhat unsatisfactory arcade dividing the N and S naves. Why this had to be renewed and the more solid Norman arcade pulled down, cannot now be said. Perhaps the C13 W tower collapsed and took part of the arcade with it. The new arcade is of only four bays and has thin piers of general lozenge shape, with semi-polygonal shafts, deep to the naves, small to the arches. Only the latter have any capitals, and even above them the mouldings of the shafts are carried on to die into the arches. The N nave clerestory was built or rebuilt at the same time. Perp also the S aisle windows. But most of the money which the Late Middle Ages gave to the church did not go into these alterations. It went to the tower which was now rebuilt N of the N doorway. It was built as an independent structure with a N and S entrance arch, though the S arch is only a few inches N of the N doorway. The tower has a quatrefoil frieze along its base, another below the bell-openings, bell-openings of two lights with a transom, semi-polygonal shafts to the entrance. arches, and on the N side traceried spandrels. Above the bell-openings detail gets more and more sumptuous, sculptured panels with chalice, host, St Katherine’s wheel, the arms of Canterbury and Ely, and so on, and elaborately stepped openwork battlements with pinnacles. To the date when this tower was completed belongs probably the equally ornate SE Vestry, built perhaps as a guild chapel, a low room with an original ceiling and outside again fully decorated battlements. A monogram occurs in the decoration of the chapel which refers to a man whose name appears frequently in the business of the Guild of Holy Trinity between 1469 and 1518. Perhaps he left the money for the building of the chapel. The date c. 1520 seems convincing, especially as documents for the building of the tower date from 1520, 1525, and 1538.

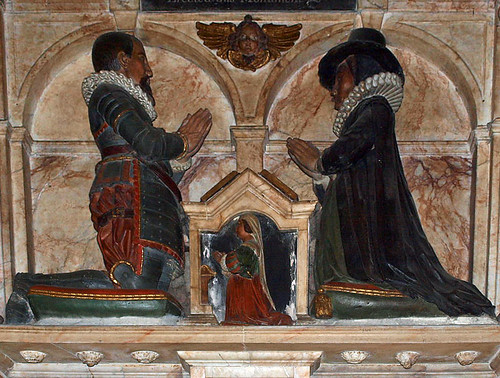

COMMUNION RAIL. Heavily twisted balusters; c. 1700. - CHOIR STALLS. Three with two Misericords. - ROYAL ARMS. Of James I; carved. - STAINED crass. E window by Hardman 1857; others of the same period (Basset:-Smith’s restoration was in 1856—8). - MONUMENTS. Brass to Thomas de Braunstone d 1401, very large figure in armour (7 ft long) formerly under thin canopy with ogee top. - Two large and quite sumptuous monuments with kneeling figures facing each other, in the accepted Jacobean pattern. They are Thomas Parke d 1628 and wife, and Matthias Taylor d 1633 and wife. Mrs Esdaile attributes the Parke Monument to G. Christmas and compares the motif of the small daughter kneeling in front of the prayer-desk between the parents to a monument at Snarford, Lincolnshire. In the upper part of the Parke Monument a recumbent skeleton. - Many pretty, late tablets, from the C17 to the early C19. Signed only E. Southwell d 1787, by Nollekens, with a seated figure of Hope in front of an obelisk.

* The W window of the N nave and the E window of the N chancel are C19 inventions.

WISBECH. It has seen great transformations, for time was when the tides swept over it, coming up the River Nene winding through the fens. It has seen the sea go back, for it was once four miles away and is now eleven. No town has prospered more from the marvellous reclamation work begun by the Romans, continued by the Dutch, and finished by Rennie and Telford, snatching thousands of square miles of fenland from the grip of the sea.

It is the second town in the county, and, its river being navigable for ships of 1700 tons, is busy with merchandise, for it has become the metropolis of the flower gardens and fruit orchards of the Cambridgeshire Fens. Those who would see what the reclamation of land can do should come this way in springtime, when the country round about is like a patchwork quilt. For weeks it is a veritable fairyland ablaze with tulips, and in due season comes the apple blossom, a wondrous sight. As for the great canning industry which has expanded so surprisingly in our time, Wisbech is one of its great centres and the figures of its canning factories (the first in England) are almost astronomical. Hundreds, thousands, millions, seem unequal to the strain.

It may be that the proudest memory of this fenland town is that of the man who struck a mighty blow for human freedom, Thomas Clarkson. His father was headmaster of the grammar school for 17 years. The school carries on in a new building after 600 years of history, but part of its old buildings may be seen; it has given an Archbishop to Canterbury, Thomas Herring. Born here in 1760, Thomas Clarkson looks down on the life of his old town from a monument 68 feet high to the top of the spire which crowns his canopy. He stands near the bridge which takes us over the river to Wisbech St Mary, and on the base of his fine monument (designed by Sir Gilbert Scott), are reliefs of a fettered slave, and of his friends William Wilberforce and Granville Sharp, Wilberforce with whom he worked throughout his life, Granville Sharp who won the historic decision in the courts that slaves cannot breathe in England. “They touch our country and their shackles fall,” wrote William Cowper, but it was Granville Sharp who made it so.

Thomas Clarkson is the most famous man of Wisbech, and rightly the town has given to him the noblest monument in its streets. The subject of human liberty engaged his attention in his early days at Cambridge, where an essay of his was received with great applause in the senate house. He made friends with Granville Sharp and William Wilberforce, and joined a committee on May 22, 1787, to work for the suppression of the slave trade. Within a year the matter was being discussed in Parliament, where it was revealed that rarely less than 50 and often more than 80 in every 100 Negroes died on their voyage into slavery. He once boarded all the ships belonging to the navy at Deptford, Woolwich, Chatham, Sheerness, and Portsmouth searching for a witness on the horrors of the trade. He travelled all over the country to keep up the hearts of the reformers after Wilberforce’s defeat in Parliament. He interviewed the Tsar of Russia, helped to found the Anti-Slavery Society, and saw the triumph of the cause. When he was 73 years old he was going blind, but he had 13 years to live, and an operation on his eyes brought back his sight after a short period of total blindness. At 79 he was made a Freeman of the City of London, but perhaps his best recognition is in Wordsworth’s sonnet, which begins Clarkson! it was an obstinate hill to climb, and goes on: -

Duty's intrepid liegeman, see, the palm

Is won, and by all nations shall be worn!

The bloodstained writing is for ever torn;

And thou henceforth wilt have a good man’s calm,

A great man's happiness; thy zeal shall find

Repose at length, firm friend of human kind.

Wisbech has lost its ancient castle, built by the Normans and made into a palace of the bishops by Cardinal Morton in the 15th century. It covered four acres and was protected by a moat 40 feet wide. It was within the old walls that King John heard the bitter news that his jewels had been lost in the Wash, and here in the troubled days of religious persecution two famous men were held in captivity, Thomas Watson, a great scholar and supporter of Mary Tudor, and John Feckenham, the last Abbot of Westminster. The history of the castle ended in Cromwellian days, and Cromwell’s Secretary of State, Thomas Thurloe, pulled down the walls and built himself a new house with the materials, Inigo Jones designing it for him. Thurloe was one of the men to whom Oliver was much attached, and with whom he would lay aside his greatness. When Cromwell was raised to the Protectorate Thurloe sent out the order to the sheriffs to proclaim him, and it was his marvellous system of secret intelligence which made it possible for a member of Parliament to say in the House that Cromwell carried the secrets of all the princes in Europe at ln's girdle. Cromwell was truly a hero to this secretary, and Thurloe wished him to accept the crown. After the Restoration he was charged with high treason, but released; it is said that he remarked that if he were to be hanged he had a black book which would hang many that went for Cavaliers.

On the site of the old castle moat now stands the museum, which claims the distinction of being one of the oldest in the country. It has a fine collection of coins, glass, and pottery from Celtic, Roman, and Saxon England, a valuable display of fenland birds, relics of the slave trade and little things associated with Thomas Clarkson; charters of the 16th and 17th centuries, a manuscript written by 12th century monks which Pepys is known to have looked at, many autographs and over 3000 coins, the Dickens manuscript from which Great Expectations was printed, a number of early atlases, specimens of Whieldon ware, and a wonderful little head of Buddha about 1600 years old. Near the museum is an old inn with structural fragments of the 15th century, and we understand that its wine vaults were part of an underground passage to the castle.

In one of the two marketplaces stands the octagon church, a ‘modem chapel of ease, and there is a modern church of St Augustine; but the only ancient church in Wisbech is that of St Peter and St Paul, a remarkable place with three nave arcades built in three centuries. This spacious church with a quaint array of roofs and over 30 windows, has a double nave and a double chancel, each with its own gabled roof, and both naves with aisles. The north nave is separated from its aisle by a Norman arcade of five bays, one of the arches carved with chevron, the others plain. Above this is the 15th century clerestory. Separating the north nave from the south is a lofty arcade from the 15th century, with a Norman arch at the western end facing the western arch of the north arcade, both part of a Norman vanished tower. The arcade separating the south nave from its aisle is 14th century and has clustered pillars; it was probably built at the same time as the arcade dividing the two chancels. One of the pillars of the chancel arch is Norman. The reredos is of stone and alabaster, with a mosaic copy made in Venice of Leonardo's Last Supper; there are canopied figures of St Peter and St Paul at the sides. There is an Elizabethan altar table and a 14th century font.

The tower is the finest feature of the church, and comes from early in the 16th century. Its three stages rise to a rich crown of pierced battlements, with eight pinnacles and a leaded roof like a small spire. Under the parapet is a cornice adorned with shields, flowers, and emblems; angels with symbols are over the belfry windows, and the stringcourses are carved with heraldry. The tower base forms a north porch and shelters a handsome 14th century doorway enriched with a band of carving of animals, birds, foliage, and grotesques, among them being little men, lions, and a dragon chasing a dog. The most interesting memorial in the church is a great brass of Thomas de Braunston, Constable of the Castle in the 14th century. It is one of the biggest brasses in England, over nine feet long, and shows the knight lifesize in armour which is interesting because it illustrates the coming of full plate armour. He has a steel cuirass, a pointed helmet, and an ornamental sword and dagger, his hands are clasped in prayer, and his feet are on a lion. A Constable of the Castle 230 years after him kneels with his wife on a dingy wall-memorial of 1633. He was a linen draper named Matthias Taylor, and both he and his wife are in long gowns and ruffs. Also kneeling on a wall are two Wisbech people who must have bought linen at Matthias Taylor’s shop, for they died a few years before him and left charities to the town. He is Thomas Parke, and kneels in armour and ruff at a desk, his wife being in a flowing gown with a ruff and a broad-brimmed hat, and on a panel of the desk at which they kneel is their daughter, with a skeleton as an unpleasant companion on a shelf above.

In unknown graves in the churchyard lie the two friends who died as prisoners in the castle, Thomas Watson and John Feckenham. Thomas Watson was one of Mary Tudor’s leading bishops, and Roger Ascham paid a high tribute to his scholarship. It has been said that he spoke incautiously of excommunicating Elizabeth, and certainly for his boldness of opinion he was more than once put into the Tower. He was a sincere Roman Catholic, and even as a bishop was allowed to have his own Roman Catholic attendant. His last days were troubled by bitter controversy on theological matters, and he died while in captivity in Wisbech Castle.

John Feckenham was the last abbot of Westminster, the son of poor Worcestershire peasants, and was a popular preacher in Mary Tudor’s reign, preaching to great crowds from St Paul’s Cross during the persecution of the Protestants. Even though he could not forgive heretics his heart moved him to do his utmost to persuade them to save themselves, and it is recorded that at one time he rescued 28 people from the stake. Mary Tudor sent him to try to convert Lady Jane Grey as she lay waiting for death, but he declared himself more fit to be her disciple than her master, and after the execution a dialogue between them was published, drawn up by Lady Jane. He was with her on the scaffold, but the only comfort he could give her was to say that he was sorry for her, for he believed that they would never meet again. When he was made Abbot of Westminster he began the restoration of the abbey. It had been much neglected, shrines pulled down, relics stolen, and it was he who found the Confessor’s coffin in some hidden place and returned it to the shrine with its old splendour. He preached the funeral sermon for Queen Mary. Elizabeth befriended him because he had befriended her in her unhappy days. He found his way to the Tower, however, for “railing against changes,” and was then thrown into prison and finally released to live in a house in Holborn. He was a good friend of the poor and was allowed to live in peace for the last few years of his life.

It is the second town in the county, and, its river being navigable for ships of 1700 tons, is busy with merchandise, for it has become the metropolis of the flower gardens and fruit orchards of the Cambridgeshire Fens. Those who would see what the reclamation of land can do should come this way in springtime, when the country round about is like a patchwork quilt. For weeks it is a veritable fairyland ablaze with tulips, and in due season comes the apple blossom, a wondrous sight. As for the great canning industry which has expanded so surprisingly in our time, Wisbech is one of its great centres and the figures of its canning factories (the first in England) are almost astronomical. Hundreds, thousands, millions, seem unequal to the strain.

It may be that the proudest memory of this fenland town is that of the man who struck a mighty blow for human freedom, Thomas Clarkson. His father was headmaster of the grammar school for 17 years. The school carries on in a new building after 600 years of history, but part of its old buildings may be seen; it has given an Archbishop to Canterbury, Thomas Herring. Born here in 1760, Thomas Clarkson looks down on the life of his old town from a monument 68 feet high to the top of the spire which crowns his canopy. He stands near the bridge which takes us over the river to Wisbech St Mary, and on the base of his fine monument (designed by Sir Gilbert Scott), are reliefs of a fettered slave, and of his friends William Wilberforce and Granville Sharp, Wilberforce with whom he worked throughout his life, Granville Sharp who won the historic decision in the courts that slaves cannot breathe in England. “They touch our country and their shackles fall,” wrote William Cowper, but it was Granville Sharp who made it so.

Thomas Clarkson is the most famous man of Wisbech, and rightly the town has given to him the noblest monument in its streets. The subject of human liberty engaged his attention in his early days at Cambridge, where an essay of his was received with great applause in the senate house. He made friends with Granville Sharp and William Wilberforce, and joined a committee on May 22, 1787, to work for the suppression of the slave trade. Within a year the matter was being discussed in Parliament, where it was revealed that rarely less than 50 and often more than 80 in every 100 Negroes died on their voyage into slavery. He once boarded all the ships belonging to the navy at Deptford, Woolwich, Chatham, Sheerness, and Portsmouth searching for a witness on the horrors of the trade. He travelled all over the country to keep up the hearts of the reformers after Wilberforce’s defeat in Parliament. He interviewed the Tsar of Russia, helped to found the Anti-Slavery Society, and saw the triumph of the cause. When he was 73 years old he was going blind, but he had 13 years to live, and an operation on his eyes brought back his sight after a short period of total blindness. At 79 he was made a Freeman of the City of London, but perhaps his best recognition is in Wordsworth’s sonnet, which begins Clarkson! it was an obstinate hill to climb, and goes on: -

Duty's intrepid liegeman, see, the palm

Is won, and by all nations shall be worn!

The bloodstained writing is for ever torn;

And thou henceforth wilt have a good man’s calm,

A great man's happiness; thy zeal shall find

Repose at length, firm friend of human kind.

Wisbech has lost its ancient castle, built by the Normans and made into a palace of the bishops by Cardinal Morton in the 15th century. It covered four acres and was protected by a moat 40 feet wide. It was within the old walls that King John heard the bitter news that his jewels had been lost in the Wash, and here in the troubled days of religious persecution two famous men were held in captivity, Thomas Watson, a great scholar and supporter of Mary Tudor, and John Feckenham, the last Abbot of Westminster. The history of the castle ended in Cromwellian days, and Cromwell’s Secretary of State, Thomas Thurloe, pulled down the walls and built himself a new house with the materials, Inigo Jones designing it for him. Thurloe was one of the men to whom Oliver was much attached, and with whom he would lay aside his greatness. When Cromwell was raised to the Protectorate Thurloe sent out the order to the sheriffs to proclaim him, and it was his marvellous system of secret intelligence which made it possible for a member of Parliament to say in the House that Cromwell carried the secrets of all the princes in Europe at ln's girdle. Cromwell was truly a hero to this secretary, and Thurloe wished him to accept the crown. After the Restoration he was charged with high treason, but released; it is said that he remarked that if he were to be hanged he had a black book which would hang many that went for Cavaliers.

On the site of the old castle moat now stands the museum, which claims the distinction of being one of the oldest in the country. It has a fine collection of coins, glass, and pottery from Celtic, Roman, and Saxon England, a valuable display of fenland birds, relics of the slave trade and little things associated with Thomas Clarkson; charters of the 16th and 17th centuries, a manuscript written by 12th century monks which Pepys is known to have looked at, many autographs and over 3000 coins, the Dickens manuscript from which Great Expectations was printed, a number of early atlases, specimens of Whieldon ware, and a wonderful little head of Buddha about 1600 years old. Near the museum is an old inn with structural fragments of the 15th century, and we understand that its wine vaults were part of an underground passage to the castle.

In one of the two marketplaces stands the octagon church, a ‘modem chapel of ease, and there is a modern church of St Augustine; but the only ancient church in Wisbech is that of St Peter and St Paul, a remarkable place with three nave arcades built in three centuries. This spacious church with a quaint array of roofs and over 30 windows, has a double nave and a double chancel, each with its own gabled roof, and both naves with aisles. The north nave is separated from its aisle by a Norman arcade of five bays, one of the arches carved with chevron, the others plain. Above this is the 15th century clerestory. Separating the north nave from the south is a lofty arcade from the 15th century, with a Norman arch at the western end facing the western arch of the north arcade, both part of a Norman vanished tower. The arcade separating the south nave from its aisle is 14th century and has clustered pillars; it was probably built at the same time as the arcade dividing the two chancels. One of the pillars of the chancel arch is Norman. The reredos is of stone and alabaster, with a mosaic copy made in Venice of Leonardo's Last Supper; there are canopied figures of St Peter and St Paul at the sides. There is an Elizabethan altar table and a 14th century font.

The tower is the finest feature of the church, and comes from early in the 16th century. Its three stages rise to a rich crown of pierced battlements, with eight pinnacles and a leaded roof like a small spire. Under the parapet is a cornice adorned with shields, flowers, and emblems; angels with symbols are over the belfry windows, and the stringcourses are carved with heraldry. The tower base forms a north porch and shelters a handsome 14th century doorway enriched with a band of carving of animals, birds, foliage, and grotesques, among them being little men, lions, and a dragon chasing a dog. The most interesting memorial in the church is a great brass of Thomas de Braunston, Constable of the Castle in the 14th century. It is one of the biggest brasses in England, over nine feet long, and shows the knight lifesize in armour which is interesting because it illustrates the coming of full plate armour. He has a steel cuirass, a pointed helmet, and an ornamental sword and dagger, his hands are clasped in prayer, and his feet are on a lion. A Constable of the Castle 230 years after him kneels with his wife on a dingy wall-memorial of 1633. He was a linen draper named Matthias Taylor, and both he and his wife are in long gowns and ruffs. Also kneeling on a wall are two Wisbech people who must have bought linen at Matthias Taylor’s shop, for they died a few years before him and left charities to the town. He is Thomas Parke, and kneels in armour and ruff at a desk, his wife being in a flowing gown with a ruff and a broad-brimmed hat, and on a panel of the desk at which they kneel is their daughter, with a skeleton as an unpleasant companion on a shelf above.

In unknown graves in the churchyard lie the two friends who died as prisoners in the castle, Thomas Watson and John Feckenham. Thomas Watson was one of Mary Tudor’s leading bishops, and Roger Ascham paid a high tribute to his scholarship. It has been said that he spoke incautiously of excommunicating Elizabeth, and certainly for his boldness of opinion he was more than once put into the Tower. He was a sincere Roman Catholic, and even as a bishop was allowed to have his own Roman Catholic attendant. His last days were troubled by bitter controversy on theological matters, and he died while in captivity in Wisbech Castle.

John Feckenham was the last abbot of Westminster, the son of poor Worcestershire peasants, and was a popular preacher in Mary Tudor’s reign, preaching to great crowds from St Paul’s Cross during the persecution of the Protestants. Even though he could not forgive heretics his heart moved him to do his utmost to persuade them to save themselves, and it is recorded that at one time he rescued 28 people from the stake. Mary Tudor sent him to try to convert Lady Jane Grey as she lay waiting for death, but he declared himself more fit to be her disciple than her master, and after the execution a dialogue between them was published, drawn up by Lady Jane. He was with her on the scaffold, but the only comfort he could give her was to say that he was sorry for her, for he believed that they would never meet again. When he was made Abbot of Westminster he began the restoration of the abbey. It had been much neglected, shrines pulled down, relics stolen, and it was he who found the Confessor’s coffin in some hidden place and returned it to the shrine with its old splendour. He preached the funeral sermon for Queen Mary. Elizabeth befriended him because he had befriended her in her unhappy days. He found his way to the Tower, however, for “railing against changes,” and was then thrown into prison and finally released to live in a house in Holborn. He was a good friend of the poor and was allowed to live in peace for the last few years of his life.

No comments:

Post a Comment