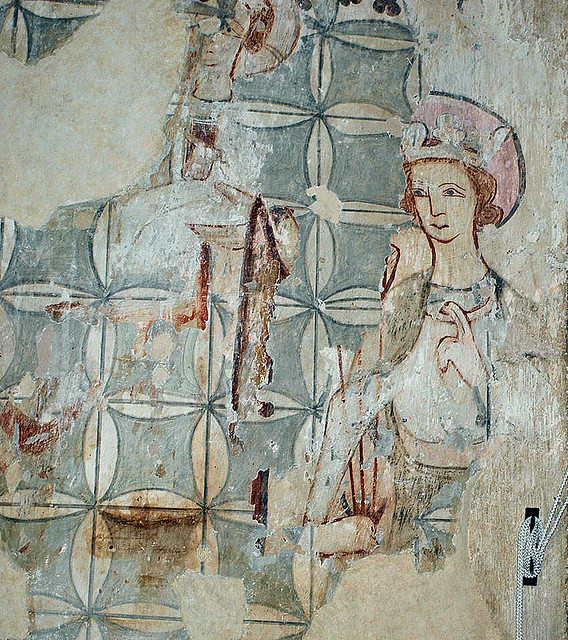

ST MARY. An eminently interesting church, not sufficiently studied. It has a Norman chancel arch with three orders of shafts, multi-scalloped capitals, and no other decoration in the arches than rolls. To the l. is one Norman colonnette with the beginning of an arch, and this may well indicate blank arcading of the altar space. The chancel is C13, see the one lancet window. This C13 work was an extension of the Norman chancel, the length of which is clear outside, especially on the S side, where the joint is visible. There was a N chapel, and its W wall has left traces. The blocked arch from the chancel also survives. The doorway to the chapel was reset in the blocked wall. The W tower is in its lower parts of the late C13. It has a single-chamfered E arch and fine W doorway with four-chamfered continuous mouldings. The latter is not usually seen, because it is covered by a two-storeyed W attachment, mostly of brick, and of indefinite date.* In it there is a re-used Perp window. Dec N aisle with charming circular E window above the altar. Late Perp S aisle windows. The building history is further elucidated by the arcades inside. They have octagonal piers on both sides, but that is as far as the similarity goes. On the N side the arcade has three plus two bays, divided by a piece of solid wall marking, no doubt, the W end of the Norman building. The three E bays have detail of the early C14, the two W bays are Dec with a slimmer pier and more finely moulded capital. These details are the same on the S side, and the N aisle windows, also those of the E bays, go with them. The later piers have at the top of each side a pointed trefoiled arch-head. Perp clerestory; also an E window at clerestory level, unfortunately blocked. Fine roof with alternating tie-beams and hammerbeams and big angels against the hammerbeams (cf. Mildenhall and also Methwold Norfolk), queenposts, and tracery above the tie-beams. - FONT. The finest C13 font in the county. Big, octagonal, with gabled arches in each panel and much big stiff-leaf decoration. Octagonal stem with eight detached shafts. - PULPIT. Perp, with arched panels and trumpet foot. - BENCHES. A delightful set with poppy-heads with all sorts of small animals, a unicorn, a tiger, etc., also a man seated on the ground with his knees pulled up. The bench backs have charming lacework friezes of different patterns. - LADDER. The ladder in the W tower may well be the original one. - FAMILY PEW. Jacobean. - WALL PAINTINGS. On one of the piers; C14. A seated figure of St Edmund King and Martyr and above it scenes from the Life of Christ emanating from a tree. Also twice the Annunciation and the Resurrection. - PLATE. Elizabethan Cup; Paten 1696. - MONUMENTS. Brass of a Civilian and wife, c. 1530, 18 in. figures. - Monument to the Styward family. tomb-chest in the S chapel with lozenges with shields. Niche above with panelled ends and a straight top. All this is purely Perp; but the lettering is Roman, and the date is in fact as late as 1568. - Joanna Bartney d. 1583. Tablet with a tree-trunk from which hangs a big shield. A sword at the foot ready presumably to cut the tree.

* The Rev. J. T. Munday tells me that a post-Reformation document shows it in use as a manor office, and suggests that the structure itself is post-Reformation. For an account of the history of the church as a whole, see his booklet, Lakenheath Church, 1970.

LAKENHEATH. It is the home of Lord Kitchener’s ancestors; here we trace the line that led to our great soldier of the people. It lies on gently sloping ground reaching toward the Fens with a wide prospect of heath and pinewood. We may come to it passing through miles of firs of all ages and forms, some tall and stately, some like crooked old men. There is one specially fine company of old trees on Maid’s Cross Hill.

As we approach the wide-spreading village two pictures haunt the memory. We imagine a venerable old man, rich in virtue and learning, fleeing vainly from the wrath of maddened rebels. We see, three centuries later, a simple man coming to the village to found a family which was to stamp its name on a most famous page in our history. Here was a rich centre of the cloth industry, whose rich men in their prosperity spent lavishly in adorning the church they inherited from Norman days. Their gargoyles guard the 14th century pinnacles of the 13th century tower. There is still the ancient room over the tower porch, and still splendid stands the Norman chancel arch, with three moulded orders. There is more Norman work on the stringcourse of the chancel wall. The 13th century font has eight richly canopied panels and nine shafts, and an ancient windowsill forms the priest’s seat. Traces of a wall-painting brought to light in the nave reveal men and angels and queer figures in the branches of a tree. A portrait brass shows a 16th century civilian and his wife, and there is an aisle monument with shields of the Stywards family, one of whom has been sleeping here since 1568.

The woodwork is magnificent. The pulpit, mounted on a beautiful stem, is a gem of 15th century craftsmanship. Angels of stone bear up the nave roof, on whose massive beams are still some 60 more angels carved in the 16th century. In the roof of an aisle are nine more wooden carvings of merry folk. The bench-ends and poppy-heads remain a gallery of fine carvings, abounding in rare workmanship and quaint conceits. One has an elephantine fish, another a hare; there are two acrobats probably modelled from strolling players who visited the village, one with his head the wrong way, the other throwing a somersault. There are priests reading books, and a man who carries a church on his back, and here, too, is that rarely illustrated legend of the tiger and the looking-glass, a quaint carving which we have seen in Salisbury Cathedral and one or two other churches, and at Little Mote, the oldest house at Eynsford in Kent. By stopping to look in the mirror, thinking it saw its cubs there, the tiger was delayed while the hunters got the cubs away.

The Stywards were ancient lords of the manor, and it was to Sir Nicholas Styward that there came as bailiff Thomas Kitchener, born at Binstead in Hampshire in 1666. Here he remained, here he was churchwarden, here he died. He lies with a dozen other Kitcheners in the shade of a big chestnut tree. There is an inscription in the church to the old bailiffs famous descendant Lord Kitchener, placed here by the London Society of East Anglians. It is odd to remember that the founder of the family here came from Hampshire in 1666 and that it was in the cruiser Hampshire that its greatest son went down at sea 250 years later.

Long before the advent of the Kitcheners the village filled a terrible page of history. It was during the Peasant Rising of 1381, when, following the Black Death, the workers sought emancipation from serfdom. John of Lakenheath, warden of the barony, fled to the abbey at Bury St Edmunds and was in hiding there when Chief Justice Cavendish was on circuit in Suffolk, putting into force the Statute of Labourers. Here Cavendish was recognised by the rebels, and sought safety in flight. Hurrying to the nearest river, he tried to reach the only boat available, but a woman thwarted him by thrusting the boat into mid-stream. He was overtaken and decapitated, and his head was borne to Bury St Edmunds, being there set up in company with those of John of Lakenheath and John of Cambridge, the prior of the abbey.

As we approach the wide-spreading village two pictures haunt the memory. We imagine a venerable old man, rich in virtue and learning, fleeing vainly from the wrath of maddened rebels. We see, three centuries later, a simple man coming to the village to found a family which was to stamp its name on a most famous page in our history. Here was a rich centre of the cloth industry, whose rich men in their prosperity spent lavishly in adorning the church they inherited from Norman days. Their gargoyles guard the 14th century pinnacles of the 13th century tower. There is still the ancient room over the tower porch, and still splendid stands the Norman chancel arch, with three moulded orders. There is more Norman work on the stringcourse of the chancel wall. The 13th century font has eight richly canopied panels and nine shafts, and an ancient windowsill forms the priest’s seat. Traces of a wall-painting brought to light in the nave reveal men and angels and queer figures in the branches of a tree. A portrait brass shows a 16th century civilian and his wife, and there is an aisle monument with shields of the Stywards family, one of whom has been sleeping here since 1568.

The woodwork is magnificent. The pulpit, mounted on a beautiful stem, is a gem of 15th century craftsmanship. Angels of stone bear up the nave roof, on whose massive beams are still some 60 more angels carved in the 16th century. In the roof of an aisle are nine more wooden carvings of merry folk. The bench-ends and poppy-heads remain a gallery of fine carvings, abounding in rare workmanship and quaint conceits. One has an elephantine fish, another a hare; there are two acrobats probably modelled from strolling players who visited the village, one with his head the wrong way, the other throwing a somersault. There are priests reading books, and a man who carries a church on his back, and here, too, is that rarely illustrated legend of the tiger and the looking-glass, a quaint carving which we have seen in Salisbury Cathedral and one or two other churches, and at Little Mote, the oldest house at Eynsford in Kent. By stopping to look in the mirror, thinking it saw its cubs there, the tiger was delayed while the hunters got the cubs away.

The Stywards were ancient lords of the manor, and it was to Sir Nicholas Styward that there came as bailiff Thomas Kitchener, born at Binstead in Hampshire in 1666. Here he remained, here he was churchwarden, here he died. He lies with a dozen other Kitcheners in the shade of a big chestnut tree. There is an inscription in the church to the old bailiffs famous descendant Lord Kitchener, placed here by the London Society of East Anglians. It is odd to remember that the founder of the family here came from Hampshire in 1666 and that it was in the cruiser Hampshire that its greatest son went down at sea 250 years later.

Long before the advent of the Kitcheners the village filled a terrible page of history. It was during the Peasant Rising of 1381, when, following the Black Death, the workers sought emancipation from serfdom. John of Lakenheath, warden of the barony, fled to the abbey at Bury St Edmunds and was in hiding there when Chief Justice Cavendish was on circuit in Suffolk, putting into force the Statute of Labourers. Here Cavendish was recognised by the rebels, and sought safety in flight. Hurrying to the nearest river, he tried to reach the only boat available, but a woman thwarted him by thrusting the boat into mid-stream. He was overtaken and decapitated, and his head was borne to Bury St Edmunds, being there set up in company with those of John of Lakenheath and John of Cambridge, the prior of the abbey.

No comments:

Post a Comment