Cards on the table, Thetford. is. a. hellhole. Whoever is responsible for traffic management should be sacked and the people responsible for its development need to be held accountable for what Simon Knott memorably describes as the "rape of Thetford". Generally I find this area of Norfolk to be amongst the most attractive of East Anglian delights but Thetford is an irradicable stain. It also appears to be fairly Godless [unsurprising] since two of its old churches are redundant and the third locked. It's a soul destroying town.

Having said that the Priory of Our Lady, obviously ruined, English Heritage owned and open, is fascinating but felt oddly under utilised. I loved it.

PRIORY OF OUR LADY. Founded for Cluniac monks from Lewes (the earliest Cluniac settlement in England) by Roger Bigod in 1103-4. The monks first occupied the cathedral, as the bishop had moved to Norwich in 1094. They began building on a new, the present, site in 1107, and in 1114 the church was taken into use. At that time probably only the E end was built. The nave must have followed quickly, and the W front was reached, it seems, about 1130-40. Meanwhile the monastic quarters were also built and indeed, except for later additions and alterations, completed.

The oldest parts are the W half of the chancel and the transepts. The chancel has aisles, and chancel as well as aisles ended in apses. As the transepts also had an E apse each, the scheme of the plan is that of the C10 abbey of Cluny. The piers between the chancel and the chancel aisles had shafts towards the chancel but segmental projections towards aisle and arch openings (cf. Norwich Cathedral and Ely). The aisles were vaulted. The transept apse was provided with blank arcading inside and demi-columnar buttresses outside. In the W wall of the S transept are tall shallow recesses. Of the upper part the pier at the junction of main apse and S aisle apse stands up highest. It has double shafts towards the high and monumental apse arch, with decorated capitals and roll mouldings in the arch. Remains are also recognizable of the gallery and a shafted clerestory window. Of the crossing, the nave and aisles, and the W front much less can be distinguished. The W front had two towers and the bay below the N tower still has some internal details (odd W respond of the arcade between N aisle and nave). To the outside there was blank arcading, probably somewhat like Castle Acre (which was also Cluniac). The W portal had four orders of shafts.

Of later additions to the church the most important are the Lady Chapel and the lengthening of the chancel, the former of the earlier, the latter of the later C13. Of details belonging to the Lady Chapel the shafts of the E window are still in situ, Of details belonging to the chancel the arcade towards the Lady Chapel remains. In the N transept a wall towards the crossing was inserted in the C14, in the N aisle a chapel for the monument of the first Howard Duke of Norfolk (d. 1485). N of the N transept sacristies were erected in the late C15.* The pulpitum stood between the W crossing piers, the rood screen one bay farther W.

The monastic buildings are early C12 along the E range of the cloister, a little later along the S and W ranges. In the E range, as usual, a sacristy lay S of the transept. It was originally apsed and later lengthened. It was followed by the chapter house, which also had an apse originally. After that the stairs to the dormitory, which was placed above this range. The slype, i.e. corridor towards the buildings farther E, is the next apartment. This had wall responds and was vaulted. The buildings farther E were connected with the infirmary and arranged in an unusual and very attractive way round their own little cobbled cloister with a well in the middle. The infirmary hall took the position of the church in the monastery. Its E end was indeed, as customary, the chapel. This range dates from the C13 , but little of details survives all along here. The other ranges round the little cloister belong to the C15. S of the slype followed the undercroft of the remaining part of the dormitory, resting on a row of round middle columns. This part was altered shortly after to house parlour and warming house. At the S end of the range the reredorter or lavatory with its flushing channel along the S side.

The s range of the cloister group contained the refectory. Its big S buttresses are a C14 precaution. The W range is not easy to read. The cellar lies well below the level of the cloister. It also had columns along its middle axis and was much changed about by cross-walls later. A circular scalloped capital from one of the columns can still be seen. At its S end were the kitchens. An outer porch was added at the N end late in the C13.

Of further buildings there is one of unknown function, a range W of the N end of the W range, detached and outside the present boundary wall. It goes under the name of Prior’s Lodge and has two C12 arches in the middle of its S wall. The smaller of them has a hood-mould on head-stops. The building has C15 and blocked C17 windows. In the walls re-set stones from the priory.

To the NW of the church is the C14 gatehouse. This is of knapped flint. The wide arches are segment-headed, and there are a three-light and a two-light window above. Turrets at the inner, not the outer angles.

The ensemble of the priory ruins is very impressive, but largely amorphous: eroded cliffs of flint.

* Here a number of carved stones in the Early Renaissance style were found, and these no doubt are connected with the plan of the third Duke of Norfolk to convert the priory into a college and make it their Norfolk mausoleum. In the end, however, the monument to Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, son-in-law of the third Duke, was transferred to Framlingham in Suffolk, where the third Duke himself was also buried.

THETFORD. A Norfolk heath, such as Old Crome painted and George Borrow loved to roam on, stretches away from it, so that this pleasant little town of five thousand people seems to have sprung up from the moorland. In the heart of it two rivers meet, the Thet and the Little Ouse, the Ouse bringing barges from the sea and leaving a small part of the town in Suffolk. It has an old, old tale, for it goes back to the days when the Church was great, to the days when the Normans came and built great churches, to the days when the Romans came and set up their defences, and to days long before that when the Ancient Briton sought security by throwing up vast mounds of earth with whatever primitive tools they could find, generally shoulder blades of oxen or antlers of deer. Far back in the mists of time lie the beginnings of Thetford.

What is called Thetford Castle is the great mound rising with acres of ramparts all round it, now a very pleasant place to walk in with trees rising from the hollows and crowning the hill. In ancient days this castle mound gave its owners command of the Icknield Way where it crosses two rivers. The land was ill-drained and largely primeval forest. The earthworks on the castle hill are the biggest defences of their kind in Norfolk. The mound rises 80 feet high and is 100 feet up the slope and 1000 round the base, where deep dry moats run between the remains of a double wall. From the top of the hill, now shaped like a crater, is a fine view over the red roofs of the town, and on the western side we see remains of ramparts and ditches known as the Red Castle and believed to be Roman. Something of an actual castle there must have been here in Norman days, for it is known that William de Warenne, who married the Conqueror’s daughter, was lord of the Castle of Thetford, but there is little to remind us of the secular power of Thetford and much to show that it must have been a famous centre of the Church.

At one tree-fringed corner of the town are impressive ruins of the old priory founded 800 years and more ago by Roger Bigod, and now under the control of the Office of Works. The shape of the priory church is outlined by parts of the lower walls, fragments towering up like pinnacles of rough flint; it is said to have been more than half as big as Norwich Cathedral, and to have had one noble tower rising from the middle of a cross and two others at the west end.

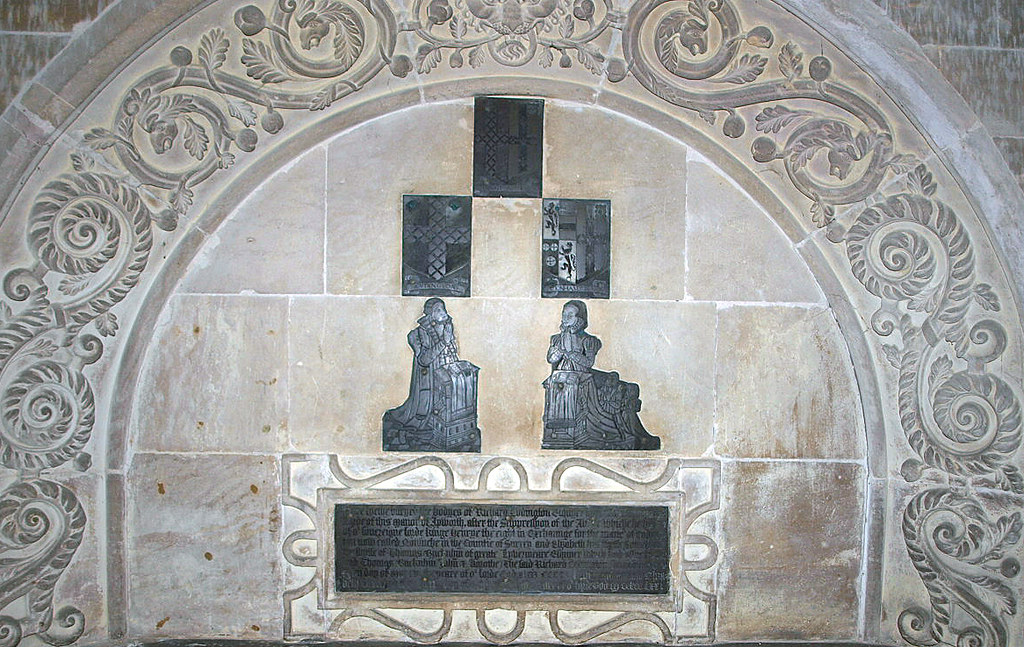

The excavations have revealed the floor of the transepts and the chapels and have uncovered the sacristy in which the monks would keep their treasures and the oven in which they would bake the sacred wafers. There are extensive remains of the chapter house, the cloister, and the buildings around, but these are mostly buried. Near the high altar have been brought to light a series of small figures rare among our medieval sculptures, and they suggest an elaborate reredos. Fragments of a tomb of English workmanship have been found in which the quality of the work is so fine that it is considered to be part of a very costly monument, probably set up not many years before the break up of the monasteries in 1540.

By the ruins of the priory stands the Tudor gateway, but most of the stones of the priory have been carried away for building What remains is beneath our feet, and among it lies the dust of powerful families of this countryside, Bigods, Mowbrays, and Howards.

The stones of Thetford speak of the days of its great fame, and remains of four ecclesiastical foundations besides the priory can be recognised. The oldest was a monastery south of the town, said to have been founded in 1020 in memory of a battle between King Edmund and the Danes. Its church has become a stable, and has an arch which led to a transept 700 years ago. Of the House of the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre, established in 1109 by William de Warenne, slight remains can be seen from the road to Brandon, and a fine thatched barn is believed to stand on the site of its church. Near the house called Ford Place, between Castle Lane and the river, are traces of the Austin Friary founded by John of Gaunt. By the boys’ grammar school stood Holy Trinity church, given by Henry, Duke of Lancaster, to a Dominican friary nearly six centuries ago, a fine arch from a transept being now built into the school.

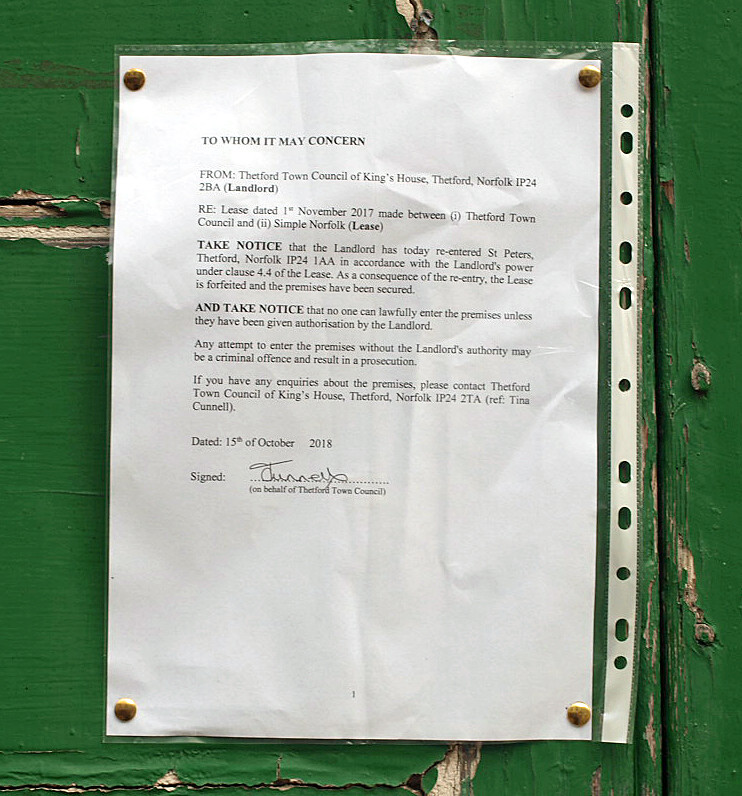

Of the three 14th-century churches still remaining in use, the oldest is St Mary’s on the Suffolk side of the river. It is chiefly 15th century as we see it, with some Norman remains. The lofty tower has a soaring arch under which stands the Norman font and there is a simple Norman doorway leading to the vestry. What is left of the altar tomb of Sir Richard Fulmerstone now makes an alabaster wall monument; he was the benefactor of the town and founded the grammar school, living in Tudor days where Place Farm stands about the old Nunnery. The flint church of St Peter, in the heart of the town, has nothing older than the 14th century, and looks better outside than in; its tower was rebuilt in 1789. By the church is what is known as the King’s House because it is thought to have been King James’s hunting lodge. St Cuthbert’s is a medieval church which was entirely rebuilt after the falling of its tower in 1851, its north aisle belonging to our own century. One of the many windows which dim its interior shows a fine figure of St Cuthbert and is in memory of a missionary who was a choirboy here. Two windows glowing with rich colour are of the Nativity and Jesus in the workshop, and in a pretty blue window, with this church and Castle Hill for a background, we see Our Lord with a group of children of our time, one bringing a bunch of daisies, one with her skipping rope, and a little boy with his Teddy Bear.

A 15th-century black and white house in White Hart Street, with an overhanging storey and fine carving, has been known as the Ancient House and Museum since 1921, when it was given to the town by Prince Frederick Duleep Singh, who made his home in this countryside. Here we may see a fine collection of the Stone Age implements for which the countryside is famed. There are coins and medals, fossils and minerals, ancient pottery, and many books, papers, and pictures concerning Thetford’s great folk. We may see more of these in the Council Room of the 20th-century Guildhall, which has a fine collection of 90 portraits of members of Norfolk and Suffolk families bequeathed by Prince Frederick Duleep Singh. Here also is the corporation regalia, with two silver maces bearing the arms of England and two gifts of 1678, a splendid sword and a mace that is among the finest in the country. By the guildhall is the Lock-up Cage, with the iron grille through which we see the ancient stocks. The oldest of the many inns in Thetford is the Bell, opposite St Peter’s church. Some of it may be part of an inn belonging to the Guild of St Mary in the 15th century, and in one of the rooms there are wall paintings discovered in our time and now preserved under a glass panel. The Dolphin Inn is 17th century, and facing the Ancient House is a dwelling which was famous as the White Hart Inn in coaching days. There is a small group of 17th-century almshouses founded by Sir Charles Harbord.

Thetford is famous not only for its Castle Hill, its priory, and its ancient ecclesiastical dignities, but for its grammar school, which is one of the oldest in England, having sprung from a school originally founded in the seventh century. Its modern foundation dates from 20 years before the Spanish Armada, and it was reconstructed 300 years later, in 1876. Associated with it is a grammar school for girls which has celebrated its jubilee and has a fine record as one of the best schools of its kind.

One of the boys passing through this school so lived in after life that his school can hardly be proud of him. He was Sir Robert Wright, Thetford born, who died in 1689. He grew up to be a companion of the infamous Judge Jeffreys, and was his colleague in the great butchery assizes after Sedgemoor. He was a man of great courage and boldness, and one of the judges of the Seven Bishops, agreeing with their acquittal. He once fined the Earl of Devonshire £30,000 for assaulting Thomas Culpepper in the king’s presence, saying that such a thing was next-door to pulling the king off his throne. As a partisan of James the Second after his flight he was imprisoned in Newgate, and died of fever in his cell.

Thetford’s more famous son was born in the century after him, and the house he was born in is now part of Grey Gables at the top of White Hart Street. We found the people of Thetford considering some memorial to this remarkable man, Thomas Paine the Radical.

Tom Paine the Renegade.

THETFORD probably feels no pride in Thomas Paine, whose name was familiar to the whole English-reading world a century and a quarter since, but no other of its sons has had such a strange, eventful history.

He was born in 1737, his father being a Quaker. Thomas, too, was in youth a Quaker. He took a boyish turn at seafaring, then became an excise officer and was discharged for neglect of duty, and after work as an usher he secured another post as exciseman, but lost it again on the ground of absence from duty.

An interest in science brought him in contact with Benjamin Franklin, who provided him with letters of introduction to friends in Philadelphia, and he emigrated there. He found work on a magazine and was soon its editor. Four months later hostilities began between the Colonies and the Mother Country and Paine circulated in the next year 120,000 copies of a pamphlet called Commonsense, advocating the immediate formation of a Republic with complete independence. He also joined up against his country, wrote stimulating appeals to hearten its opponents, and became secretary of the Committee of Foreign Affairs.

For his services, which he himself claimed were as important as those of George Washington, he received, besides money payments, the forfeited estate of a landowner who had been loyal to England. After the war he returned to Europe with a model of an iron bridge he had invented, but nothing came of that. Then he began to write against the war policy of Pitt. The Government left him alone until he answered Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France by his book on The Rights of Man, which was received with frantic delight in France. Then he was indicted for treason. He, however, escaped to France, where he was elected to the French Convention, while England made him an outlaw.

Still acting as a self-appointed adviser of nations, he sensibly suggested that, instead of killing their king, and so alienating American sympathy, France had better imprison Louis during the revolutionary war and then perpetually banish him. This displeased Robespierre, who threw him into prison and put his name on the list for the guillotine, his life being saved only by the fact that when his turn for beheadal came he was lying unconscious with fever. When Robespierre fell Paine was released.

It was at this time that he wrote his Age of Reason, and he also wrote a bitter attack on Washington. When he returned to America he found that his popularity had waned. His Age of Reason and his attack on Washington were deeply resented, and in the last seven years of his life he lost his self-respect and his social standing. William Cobbett, who had been one of his stoutest opponents, brought his neglected bones to England from New Rochelle, where his estate was, and where they had been buried.

Tom Paine was an attractive writer. His style was direct, clear, and incisive. Essentially he was an advocate-seeing only one side of a subject and using the method of attack against those who saw other sides. The positions he so hotly attacked are not held by 20th-century Christian intelligence. Possibly he helped to clear away some rubbish of ignorance and error, but his way of doing it was crude and offensive. He was a clever self made man, but at every stage in his life he fell into failure. He had no sensitiveness and no inherent taste. America took him up and dropped him. France took him up and dropped him. He dropped his own country, and no reason is known for his doing it. He was the completest specimen of that rare creature, a renegade Englishman.