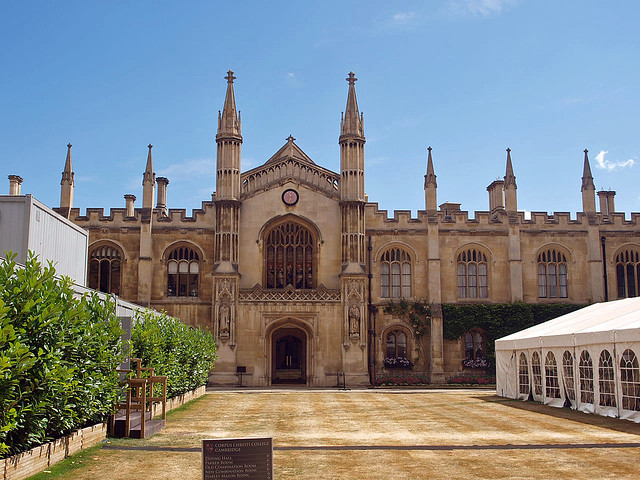

Inside the Court the Chapel is placed opposite and in line with the gatehouse. It has a facade in the tradition of the Royal Chapels of the Perp style and the so-called Commissioners’ churches of c. 1820-30. The CHAPEL interior has the stall-backs of the demolished chapel which was consecrated in 1613 and one group of canopied seats separated by over-slim columns. The E end was added in 1870 by Arthur Blomfield who found it necessary even here to demonstrate his faith in E.E. rather than Perp. The altar PAINTING is by Elisabetta Sirani. The STAINED GLASS in the N and S windows is French c 16, the Death of the Virgin earlier than the others. The E window is by Heaton, Butler & Bayne, 1881 (TK).

It does not seem venerable as we come to it from Trumpington Street, but when we pass from its front court into the smaller one on its north side we are in the first closed quadrangle built all at one time in Cambridge, erected when the college was founded in 1352 by two guilds of wealthy townsfolk. For a long time the oldest church in Cambridge, St Benedict’s, was the college chapel. The old court has been much changed but has still an atmosphere of early days. Stepped buttresses support the plastered walls, and in the quaint array of windows are dormers in the roofs of mottled tiles, plain and trefoiled lancets, and a new window with a memorial to Kit Marlowe and John Fletcher, the Elizabethan dramatists, who were undergraduates here. In the room above have been found remains of early painted decoration, and curious ledges above the staircase, made perhaps for beds. A new sundial on this north range, made to tell summer and winter time, has the Latin motto The World and its Desires pass away. Near the door by which Archbishop Parker entered his rooms is an old pelican in her piety.

Imposing with its battlements and turrets, oriels and bay windows, the modern court has a fine gateway at the head of a flight of steps; over its vaulted archway is a niche, and heads of kings and queens adorn the windows. At the entrance to the new chapel, on the east side of the court, are pinnacled turrets with niches sheltering figures of Sir Nicholas Bacon and Matthew Parker. The chapel walls are enriched with fine stone tracery, a beautiful altarpiece showing Mary and Elizabeth with Jesus and John, an altar cross with lilies and grapes and a pelican, and lovely candlesticks. Among the pictures in the old foreign glass filling four windows we see the Nativity with the shepherds peeping into the stable, the death of the Madonna, and Christ before Pilate. In the top of the windows are figures and shields, at the foot are saints and apostles. Two handsome seats with panelled backs and fluted pillars supporting arched canopies are from the old church.

The hall, lofty and airy, has windows blazoned with heraldry and a splendid gallery of portraits on walls panelled with linenfold. Among them are Matthew Parker, William Colman (by Romney), Dean Lamb, Dr Richard Love (by Mytens), Sir Nicholas Bacon, Archbishop Tenison, Edward Tenison, Dean Spencer (by Van Der Myn), and Sir John Cust (Speaker of the House of Commons) by Reynolds. In the windows lighting the stairway to the hall are tiny scenes in panels of old glass.

The library is famous for the rare gift of Matthew Parker. When he was Archbishop of Canterbury in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign he had an unrivalled opportunity of collecting manuscripts scattered about the country after the dissolution of the monasteries, and he gave to his college one of the richest collections now in England. Among its greatest possessions is the earliest manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. He found this manuscript, a thousand years old, open at the page recording the death of Alfred in 892. The holes in the page have a curious origin. This sheet of vellum was made from sheep whose skins were not too clean, and it was the ravages wrought by ticks that made these holes in the parchment, so that we behold here, not only the writing of Saxon scribes but the work of Saxon pests. Another treasure here is the Chronicle of Matthew Paris, delightfully illustrated by his own artistic hand; this was open at a page where he drew on the bottom margin an attack on a Genoese galley by Pisan warriors, whose shafts are hurtling past the Genoese bowman’s head. There are many Saxon manuscripts showing their writing and their drawing, a magnificent Roman one of the 5th century with a picture of St Luke in a toga, and a Celtic one with an illustration in enamelled colours. Here are the Canterbury Gospels of the 6th century, sent by Pope Gregory to Augustine, his gift to the men of Kent; a 12th century Bible, finely illuminated, from the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds; and the original of the Forty-two Articles of Religion of the time of Edward the Sixth, before they were reduced to Thirty-nine by Matthew Parker. There are early printed books (two by Caxton), and the Lewis Collection of gems, coins, and Greek and Roman antiquities.

Imposing with its battlements and turrets, oriels and bay windows, the modern court has a fine gateway at the head of a flight of steps; over its vaulted archway is a niche, and heads of kings and queens adorn the windows. At the entrance to the new chapel, on the east side of the court, are pinnacled turrets with niches sheltering figures of Sir Nicholas Bacon and Matthew Parker. The chapel walls are enriched with fine stone tracery, a beautiful altarpiece showing Mary and Elizabeth with Jesus and John, an altar cross with lilies and grapes and a pelican, and lovely candlesticks. Among the pictures in the old foreign glass filling four windows we see the Nativity with the shepherds peeping into the stable, the death of the Madonna, and Christ before Pilate. In the top of the windows are figures and shields, at the foot are saints and apostles. Two handsome seats with panelled backs and fluted pillars supporting arched canopies are from the old church.

The hall, lofty and airy, has windows blazoned with heraldry and a splendid gallery of portraits on walls panelled with linenfold. Among them are Matthew Parker, William Colman (by Romney), Dean Lamb, Dr Richard Love (by Mytens), Sir Nicholas Bacon, Archbishop Tenison, Edward Tenison, Dean Spencer (by Van Der Myn), and Sir John Cust (Speaker of the House of Commons) by Reynolds. In the windows lighting the stairway to the hall are tiny scenes in panels of old glass.

The library is famous for the rare gift of Matthew Parker. When he was Archbishop of Canterbury in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign he had an unrivalled opportunity of collecting manuscripts scattered about the country after the dissolution of the monasteries, and he gave to his college one of the richest collections now in England. Among its greatest possessions is the earliest manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. He found this manuscript, a thousand years old, open at the page recording the death of Alfred in 892. The holes in the page have a curious origin. This sheet of vellum was made from sheep whose skins were not too clean, and it was the ravages wrought by ticks that made these holes in the parchment, so that we behold here, not only the writing of Saxon scribes but the work of Saxon pests. Another treasure here is the Chronicle of Matthew Paris, delightfully illustrated by his own artistic hand; this was open at a page where he drew on the bottom margin an attack on a Genoese galley by Pisan warriors, whose shafts are hurtling past the Genoese bowman’s head. There are many Saxon manuscripts showing their writing and their drawing, a magnificent Roman one of the 5th century with a picture of St Luke in a toga, and a Celtic one with an illustration in enamelled colours. Here are the Canterbury Gospels of the 6th century, sent by Pope Gregory to Augustine, his gift to the men of Kent; a 12th century Bible, finely illuminated, from the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds; and the original of the Forty-two Articles of Religion of the time of Edward the Sixth, before they were reduced to Thirty-nine by Matthew Parker. There are early printed books (two by Caxton), and the Lewis Collection of gems, coins, and Greek and Roman antiquities.

No comments:

Post a Comment